Padmaavat movie review: Bigotry, biases ki beauteous raas-leela

Padmaavat is offensively chauvinistic, blatantly right-wing, and quite unabashedly anti-Muslim.

Padmaavat (3D) (U/A) 164 min

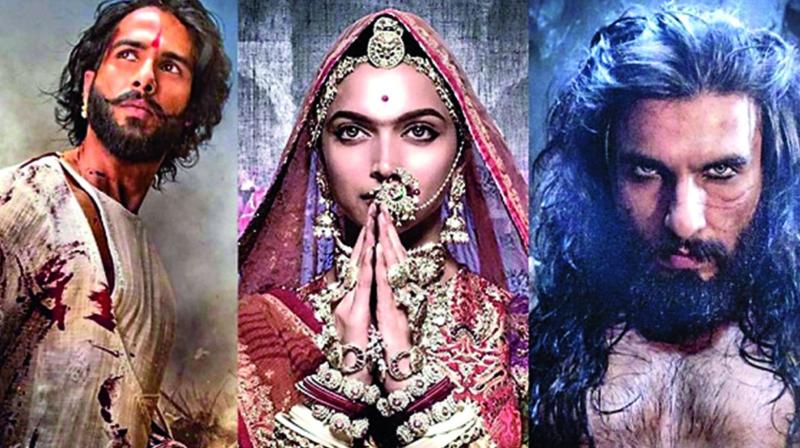

Cast: Deepika Padukone, Ranveer Singh, Shahid Kapoor, Anupriya Goenka, Aditi Rao Hydari, Raza Murad, Jim Sarbh

Director: Sanjay Leela Bhansali

In my memory no film has been battered so black and blue for so long like Padmaavat nee Padmavati has. So just the fact that it has actually arrived in theatres despite the bus burning, mob violence and threats deserves repeated standing ovations. But, sadly, Padmaavat the film is exactly what many suspected after watching its trailer. It is, at one level, what has come to be know as Bhansali’s template magnum opus — movies that overwhelm us with their beauty and devotion to perfection at the expense of human drama. At another it’s a film that lays bare Bhansali’s own politics.

Padmaavat is offensively chauvinistic, blatantly right-wing, and quite unabashedly anti-Muslim.

At some point, when the Karni Sena calms down enough to sit and watch this film, they will realise that Padmaavat doesn’t just outdo their balderdash and vile pomposity, but it also champions all their prejudices and xenophobia.

The film opens to a very unbrahminical sight. In 13th century Afghanistan, Jalaluddin Khilji (Raza Murad) is sitting on his throne chomping on a large piece of meat and nursing ambitions of conquering Hindustan. Next, characters begin to appear in order of their significance to the story, the scenes and dialogue disclosing little apart from their key trait that will set the course of their action and drive the film’s meagre plot.

Alauddin Khalji (Ranveer Singh), Jalaluddin’s nephew, walks in with the swagger of a top dog biding time, itching to go rogue. He presents his chacha with a nayab bird and then asks for his daughter Mehrunissa’s (Aditi Rao Hydari) hand in marriage.

Alauddin’s character, he announces, pivots on an obsession — the zid of possessing all that is nayab, i.e. rare, unique, magnificent. In the enchanted forest of Sinhala (Sri Lanka), meanwhile, dwells a creature of sublime beauty and inner glow — Rajkumari Padmavati (Deepika Padukone). We catch her chasing a hiran, an activity that excites all Indian princes, princesses and spoilt superstars when they find themselves in the woods. She shoots at what she thinks is a deer, only to find Rawal Ratan Singh (Shahid Kapoor) impaled by her arrow.

He faints on her and she nurses him back to life in a Buddhist cave. This introductory event, we discover over time, becomes a pattern in their relationship — he shall wilt and she shall bail him out.

Ratan Singh, king of Chittor, who mostly wears one expression — that of painful constipation — was wandering around the forest to collect pearls for his wife (?!). But has now fallen for the woman who shot him. They marry.

Meanwhile, Jalaluddin, now Sultan-e-Hind in Delhi, presents his land-conquering bhatija with a devoted slave. Malik Kafur (Jim Sarbh) exists only as the butt of several homophobic jokes.

In Chittor, an interaction between the new rani and a creepy Rajguru goes decidedly weird and, on Ratan Singh and Padmavati’s suhag raat, he’s caught leering. Ratan Singh banishes him, setting free yet another malevolent Brahmin to plot revenge.

Ratan Singh is a principled if slightly dim man who stares at his beauteous wife with a daffy expression. He’s in love and repeatedly bombastic about Rajput values and valour.

Padmavati is smart and in love. Soon Rajguru finds Alauddin and baits him with a nayab thing, the beauty of Padmavati. Thus initiating Alauddin Khilji’s ek jung husn ke naam. A laborious siege of Chittor ensues that, over the course of the film’s pupil-dilating 2 hours and 44 minutes, involves swirling golden sand, several CGI battles, strange negotiations followed by stranger meetings, and, eventually, the end game.

One of the problems with Bhansali’s narrative style is that since all the sets, each scene is created at a grand scale with excess being the rule of thumb — movement of a large number of people is choreographed and synchronised while paying acute attention to getting the littlest things not just right but dazzling enough to add shine and seductive charm to the spectacle — he is too invested to then let them be part of the background, the setting.

No doubt the perfection and beauty of some of these scenes is transcendental. But the focus on them makes the people and their story peripheral, and the narration stutters. So while we admire 800 perfectly placed palanquins as they emit creatures in red at one exact moment, and stare at the huge, billowing white shrouds covering cannonball machines against a perfect sky, Alauddin becomes obsessed with Padmavati all too suddenly, Ratan Singh-Alauddin’s confrontations are all too limp, and raja-rani’s love scenes too fleeting. Luckily, Deepika Padukone’s beauty is extreme. She is also very expressive, precise and was poised for more. However, not counting the ghaghra-choli dance routines, she gets little screen time. Despite that, and despite the fact that Shahid Kapoor looks slightly cockeyed and stupid, she gives us exciting glimpses of their love and lust.

Mostly Shahid and Deepika have no energy flowing between them. Yet she makes the Holi scene very sensuous. But it had barely begun when it ends, with a hug so inappropriately platonic when it should have been full-on coital.

Though Shahid does get better, it’s too late, too little.

Padmaavat belongs to Ranveer Singh who does all the heavy lifting here. With his antics, tantrums and swag, he creates enough drama in the little tent pitched at the foot of Chittor fort to carry the film. He deserves and gets a lot of screen time. Repeatedly appearing with heads of men he has killed on a spear, he gets to caress his own body and the bodies of many women, and conjures, with boorish compulsion, agony and ecstasy over his obsession with a woman he has never really set his eyes on. I felt passion for his passion.

At the heart of Padmaavat, a languorous, extravagant costume dance-drama, is a simple love triangle where a bad man covets a good man’s pious wife. And within that tale, between the good and bad, between the perfect folds of ghaghras and the glint of a thousand nose rings swings Bhansali’s own bigotry. While he is seducing us with beauty, he is simultaneously reinforcing prejudices and a regressive worldview.

This disturbing subtext takes centre stage all too often. Alauddin is barbaric. A crass, uncouth, deceitful creep fashioned after Khal Drogo from the Game of Thrones, he wages what’s perhaps the first imagined love jihad. He also, at one point, burns pages of history that don’t mention him.

Haughty Rajputs don’t just appear to boast about the valour of their race, we even get to watch one of them swing his sword at the enemy after his head has rolled off.

The worst is kept for the last. Padmavati’s johar — where women choose death over life to protect the honour of dead men — begins with seeking her husband’s permission to kill herself. She then delivers what we can call the film’s keynote address to a large group of women, invoking the special powers and sanctimonious divinity of married Hindu women. Of course one can’t be anachronistic and expect women in 13th-14th century Rajasthan, fictional or factual, to hold forth on patriarchal abuse and demand equal rights. A story is what it is. But, as we know all too well by now, art is politics.

And filmmakers, in exercising their choice of what to show and how to show it, reveal their own politics. One should, perhaps, not be too surprised. For a while now, especially since he’s acquired two intertwined muses whose midriffs he’s rather fond of, Bhansali has pitched his tent to the right of centre. It’s telling that Bhansali is only drawn to women who burn bright for a bit, to light up his screen in lavish lehnga-cholis, striking irresistible poses, but amount to nothing without their men.

As if the johar scene, in which a sea of women in matrimonial red march to their fiery death, was not repulsive enough, he actually shows a pregnant woman’s belly moving towards the pyre.

Glamorising, eulogising and then stooping to turn the imposed violence of johar into some sort of sacred, mystical, purification ritual is the kind of crass exploitation not expected from a filmmaker of his skill and calibre.

That the legend of Padmavati appeals to Rajputs is not just a disturbing clue to how much they value women, but also a sad insight into the stories the vanquished need to tell themselves to survive. A proud, patriarchal race that has repeatedly lost battles had to spin tales of valour to be able to live with themselves.

But from a man who has dedicated Padmaavat, his third magnum opus, to his dead dog — Lady Pogo — I’d really like to know why he is so keen on repeatedly telling us stories where women are all too easily sacrificed at the altar of male pride, while he sits there, painstakingly ensuring that each piece of burning coal they chuck into their pyre has that perfect golden-orange glow.