Mahabharata explosion

Last monsoon, house-sitting for a friend in Goa, I took a photo of a gorgeous purple flower on her front porch. Spread wide with curly stamens, the flower was brash and a bit vulgar, bobbing on the vine in front of me. I posted the picture to Instagram with the caption: anyone know what this is called? And in two seconds, the replies started coming in. The scientific name for the flower was passiflora incarnata, or the passionflower, known locally in India as the Krishnakamal. But now, here’s where it gets interesting: the flower is also called “paanch Pandava” for the five Pandava brothers from the Mahabharata, because there are five raised anthers in the middle, around a centre that is interpreted to be the god Krishna, and surrounded on the outside by a hundred filaments for the hundred Kauravas who were their enemies.

Wherever we go in India, myths are not far behind, they’re part of our genetic make-up, the code we learn from our grandparents and pass on to our children. Arjun and Krishna, Ram and Lakshman, Hanuman and Ganesh, they’re spoken of in most Indian homes as though they are almost part of the family. It’s what you and I — presumably city people — have in common with someone from the remotest village in this country — we know the names of the people in their oldest stories and vice versa. Even if the god being worshipped is some sort of local deity, we know that at some point, his or her story will tangle up with the basic canon, and suddenly, it grows familiar again. Our gods are human even in their divinity, they make mistakes, have favourite children, fight with each other and make up. Our longest story — the Mahabharata — holds together several themes within its pages: family dysfunction, beautiful women seeking revenge, the need for duty and millennia-old gossip that is still interesting to this day.

When I began writing my version of the Mahabharata — The One Who Swam With The Fishes is the first of a series retelling the epic from the point of view of the women as young girls — I realised how fascinating it all still was for everyone else. Whenever I mentioned it at a party, people would say, “Oh, I’m looking forward to that!” Even my publicist was quite confident about how it would do. “It’s mythological fiction,” she said, taking a sip of her coffee, “People are really into that.” Later, when the book came out, I did a tour of Delhi’s bookstores to say hello and sign copies. Compared to my previous books where the store had only stocked five copies, maybe ten at most, here I was signing whole stacks of books: fifteen, twenty, thirty. Right in front, I could see other works of “myth lit” — Amish’s books front and centre, yes, but also next to him a whole cluster: Devdutt Pattanaik, Bibek Debroy, children’s versions, collections of short stories, management tales, graphic novels, there seems to be a Mahabharata explosion in literature right now, and it’s not slowing down at all.

“It’s the vastest story ever told,” says Jai Arjun Singh, freelance writer and author, who frequently writes about the Mahabharata in popular culture and fiction, “(Authors are drawn to it) because of the potential it carries. When you have a story like that, it becomes natural to turn to it.” Just looking at the results page on Amazon after searching for ‘Mahabharata’ is daunting. Twenty pages of results, most of them fiction and differing points of view. Take these descriptions:

From Ms Draupadi Kuru:

After The Pandavas by Trisha Das: “Draupadi is bored of Heaven. Yes, it’s beautiful and perfumed and perfect, but it’s been a few thousand years of the same thing every day. There is only one way to escape: Krishna. He can never say no to her. So she gets her gang of women together — Amba, Kunti and frenemy Gandhari — and off they go to New Delhi, on Earth, where so much has changed and so much remains the same.”

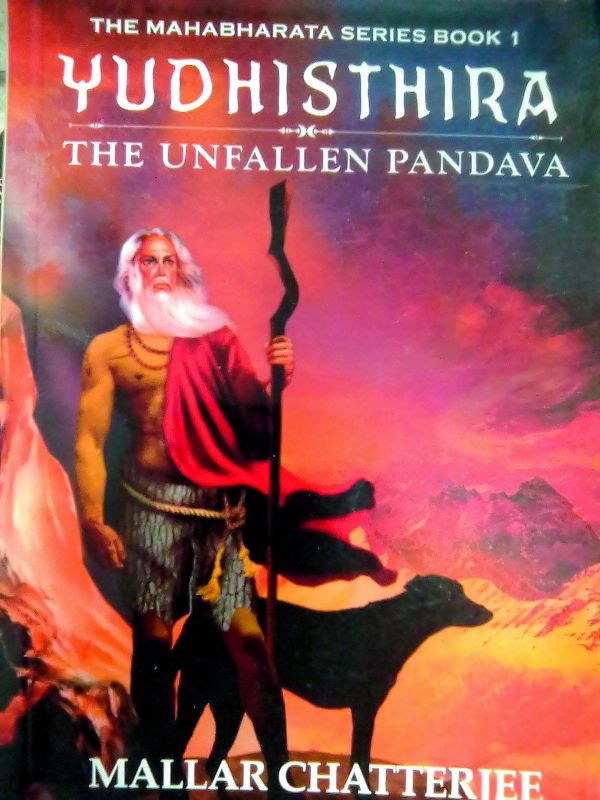

From Yudhisthira:

The Unfallen Pandava by Mallar Chatterjee: “In the process of narrating the story, he examines his extremely complicated marriage and relationship with brothers turned co-husbands, tries to understand the mysterious personality of his mother in a slightly mother-fixated way, conducts manic and depressive evaluation of his own self and reveals his secret darkness and philosophical confusions with an innate urge to submit to a supreme soul.” “Some writers have done a very lazy version of it,” says Singh, “They already have a story so they just sex it up or modernise it or whatever. Then you get books that are derivative in a bad way.” But since Indian readers don’t seem to be tiring of the myth, even stretching out their hands like so many Oliver Twists, there isn’t a shortage of choices for them.

But this need to tell an ancient story from a different point of view is not a new phenomenon. It’s been happening across epics and across literary canons, internationally authors like Rick Riordan take Greek or Norse myths and turn them into young adult phenomenons. Closer home, Draupadi is a favourite, for example. Both Chitra Bannerjee Divakaruni and earlier, Pratibha Ray have used her as a central character, spinning off from the question: what was it like to have five husbands? Both come to the same answer: that Draupadi would look for some sort of spiritual satisfaction outside her marriage: Divakaruni’s princess turns to Karna, Ray’s Yajnaseni to Krishna. Why then does it suddenly feel like we’re having a mythological literature explosion? Why now instead of a decade or two ago? I asked Karthika Nair, author of Until The Lions, a version of the Mahabharata done in verse and through the eyes of several sidelined characters. “I don’t think that the phenomenon is one of a new market so much as of greater media spotlight currently on the mythology-based literature,” she says.”

There are so many genres covering myths right now, she adds, but then corrects herself a little later: “Post 1967, Amar Chitra Kathas were often the first indigenous children’s books one read, and they covered myths with almost exhaustively perspectival tellings. Looking back, that was a fascinating approach (though the iconographical representations of good and evil remained troubling): an ACK comic book on Ghatotkacha firmly placed him as the hero; just as the one on Jarasandha highlighted that king’s accomplishments quite as clearly as his fatal flaws.” Amar Chitra Katha brought the myths to light for the first time for several people now in their thirties. I’m even idly putting together a theory that connects the need millennial writers have to retell the epics by how likely they were to have read Amar Chitra Katha in their youth. My own copies are bound and dog-eared, loved into crumbling pages and memorised illustrations. I even thanked them in my acknowledgements, that’s how big I think my debt to the comics is.

This need to tell an ancient story from a different point of view is not a new phenomenon. It’s been happening across epics and across literary canons

This need to tell an ancient story from a different point of view is not a new phenomenon. It’s been happening across epics and across literary canons

“I think Indian publishing has come alive to the sheer potential of myths,” says Nair, “The fact they provide rich and inexhaustible templates for genre writing, something European and American publishing discovered about Greek and Nordic mythology a few decades ago.” She also points out that many books on the Amazon results page were published in different decades and in different languages, and maybe: “more like a resurgence than an emergence — which is a very welcome upshot.” I wonder why it’s the Mahabharata that gets so many versions though. The Ramayana is equally popular and yet, less riffed on. And we don’t even speak of other forms of mythology such as Sikh literature or folk tales to name just a few. Both Nair and Singh think — at least among the Indian writing in English books — that it’s because the Mahabharata offers more scope to novelists. They both use the phrase “shades of grey” to refer to the epic.

“It’s much more complex,” says Singh, “It’s so morally ambiguous. Ram is still seen as a god on earth, so an author would be taking a bigger risk playing with the Ramayana.” “One also often hears that the Ramayana is about ideals: the ideal man, the ideal son, the ideal brother, the ideal devotee,” says Nair, “What one tends to forget (as Arshia Sattar brilliantly reminds us in Lost Loves) is the price paid in the journey to idealness and that journey itself.” One thought I keep circling back to, even as I read more and bury myself even deeper in the epic in preparation for my next book: is all this myth lit love connected somehow to our current political climate? In other words: is Hindutva informing our reading (and in my case writing) decisions?

“The growth of Hindutva is harking back to a supposedly glorious past,” says Singh, “That’s not to say all writers are doing it for the same reasons, but some are cashing in on the zeitgeist. Some are even cynically tailoring their writing to appeal to a religious readership.” “I cannot speak for anyone else, but the way I see it, Hindutva tries to homogenise Hinduism, which is more a vast, interconnected corpus of beliefs and traditions, scriptures (many of which contradict each other, as is natural in any living system), literature and lore than a religious monolith,” says Nair, “Hindutva fears multiplicity, and Hinduism, as we have known it in South and South-East Asia for centuries epitomises the multiple — despite all its deeply-entrenched problems of inequality, of exclusion and hierarchy, this is undeniable.”