26/11 Ten Years Later: Pak must not export terror with impunity

The idea is to ensure Pakistan no longer thinks it can export terrorism to India with impunity and without consequences.

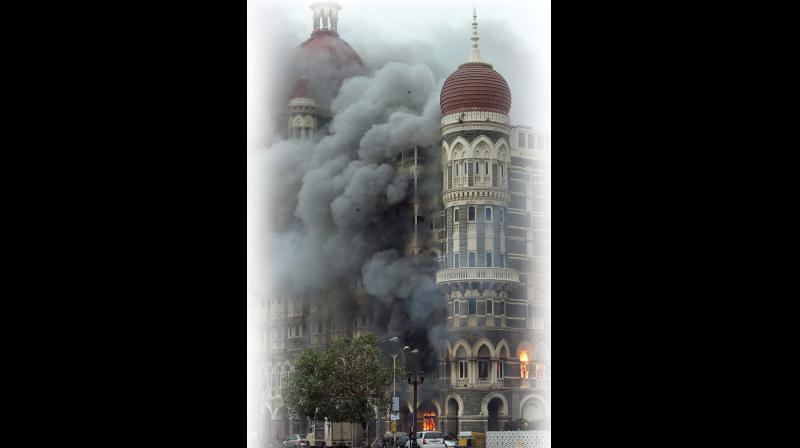

It may be ten years since Ajmal Kasab and his band of kalashnikov-wielding terrorists took Pakistan’s strategy of destabilising India to a whole new level by attacking the unsuspecting populace of Mumbai, killing 166 innocents over a three-day siege of India’s financial capital, drawing stark parallels with New York and 9/11. Mumbai has never been the same again. And despite Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s half-hearted outreach when he invited Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif to his swearing-in, India-Pakistan ties, marked by suspicion and distrust, have only worsened. The mastermind behind 26/11 continue to get state protection and will remain tools that Pakistan will use as instruments of terror. Clearly, there can never be an Agra 2.0. Strategic strike or no, the ‘Naya Pakistan’ leader Imran Khan’s noise about a Kartarpur corridor of peace, already marred by the appearance of posters of ‘Bhindranwale 2020’ at Nankana Sahib, and the continuing instability in militancy-stoked Kashmir is a sign that the Pakistan Deep State will continue to thwart India’s rise as a South Asia power.

The old saying that ‘soldiers are always preparing to fight the last war’ also applies to combating terrorism. Quite like armies that spend enormous amounts of time trying to understand how they could have fought the last war better, security forces often focus on terror attacks of the past to prevent them from recurring.

History tells us while incidents of ‘garden variety’ terrorism repeat themselves there is almost never a repeat of ones that are more spectacular in scope and scale. This is partly because the gaps in security have been filled, and partly because a repeat incident is unlikely to have the same impact or shock value as the first attack. Except for the repeated targeting of Mumbai’s local trains, almost all the other major incidents of terrorism have been one-off events — the attack on Parliament, the bombing of the Jammu and Kashmir Assembly, the 1993 serial bomb blasts in Mumbai, or for that matter, the 26/11 siege of Mumbai by terrorists. In all likelihood, there won’t be another 26/11; but there will be other attacks that are just as spectacular.

After 26/11, Pakistan-based terror groups have tried to carry out audacious attacks which aimed to cause either mass casualties or grievous damage to Indian military assets — the July 2015 terror strike in Gurdaspur where bombs were placed on a railway track to blow up a train , or the Pathankot airbase attack in Jan 2016 in which no aircraft was damaged , or the series of bomb blasts in 2017 on rail tracks in UP and Bihar. Each of these strikes, had they succeeded, would have confronted India with the same stark policy choices on how to respond as the country faced after 26/11.

Therefore, while it is imperative to address the vulnerabilities exposed by past terrorist attacks in order to prevent similar strikes in the future - after 26/11, hotels heightened security protocols, coastal security was strengthened, National Security Guard [NSG] hubs were set up to ensure quick response, institutional and legal reforms were undertaken - it is even more critical to anticipate and game the next big terror attack which will seek to exploit vulnerabilities not yet on the radars of security agencies.

At a time when Pakistan has once again been ratcheting up jihadist violence in Jammu and Kashmir and doing everything possible to reignite the insurgency in the state, opening new fronts in mainland India by proxy terror groups to stretch security agencies capabilities is something India should be prepared for. Already, strenuous efforts are being made by Pakistan to revive the Khalistan movement. But even more dangerous will be Pakistani efforts to recruit Indian Muslims to the jihadist cause.

Since the early 2000s, Pakistan managed to do this with the Indian Mujahideen, which was responsible for a spate of attacks before the network was demolished. However, rising social tensions and communal polarisation in India could make the task of Pakistani agent provocateurs trying to incite Indian Muslims against the Indian State, much easier.

The Pakistani reason for trying to recruit Indians to fight their own state flows from the fallout of 26/11. Pakistanis have found it exceedingly difficult to live down the arrest of a Pakistani national — Ajmal Kasab — and the subsequent unveiling of their sinister plot. This is a mistake they would like to avoid in the future. Using Indians to attack India could give Pakistan much needed plausible deniability. The use of Indians as terror proxies is important not just to avoid an external backlash but also to limit the possibility of an internal blowback, something that Pakistan is familiar with. In the years since 9/11, and particularly around 2004 when, because of both international pressure and domestic compulsions, Pakistan tried to regain control over its own jihad factory, not just in the Tribal Areas straddling the Western border with Afghanistan but also along the Eastern border with India.

The effort increasingly, is to keep jihadist terror organisations on a tight leash so that they serve the interests of the Pakistani state, instead of going rogue. The entire ‘mainstreaming’ project is part of this effort. [8] But even as jihadist groups are ostensibly sought to be demilitarised and mainstreamed for public consumption, their terror wings remain intact. The only difference is that unlike the pre-26/11 period when terror groups operated with complete impunity and openly owned their jihadist operations (or even pre-2004, before the then Pakistani President General Pervez Musharraf assured the world that he would not allow Pakistan territory to be used as a staging ground for acts of violence against India), today, terror groups no longer function as openly as they once did. There is no official endorsement of these groups, public grandstanding is discouraged, media coverage of their activities is tightly controlled, if not entirely shunned, and recruitment has gone underground (there is no more open inviting people to jihad with phone numbers of recruiters splashed as graffiti).

But, the bottom line is that while Pakistan has become more discreet in using jihad, there is absolutely no sign of it dismantling the jihadist infrastructure. In the words of S.Paul Kapur, “support for militants has not simply been one among many tools of Pakistani statecraft. Rather, the use of Islamists militants has been a primary component of Pakistani grand strategy.” Since Pakistan cannot compete with India in the conventional military space, it seeks to balance the military equation through the instrumentality of ‘sub-conventional offensive warfare.’

Given that jihad continues to remain the central pillar of Pakistani grand strategy, and that Pakistan today exercises far greater oversight and control over jihadist organisations, the fiction of non-state actors operating on their own volition from Pakistan stands exposed. In other words, the next big terror attack in India will be decided and directed by the Pakistani state. What is more, regardless of how much Indian security agencies anticipate, prevent, prepare, pre-empt or, if it comes to that — put out an attack, it is highly likely that there will be another attack with Pakistani fingerprints all over it.

The question is: how will India respond? One option is to exercise restraint and not undertake any kinetic action — not only because of the risks of escalation that such an option entails, but also because while military response (even a limited one) will be emotionally satisfying, it won’t solve the problem of terrorism. Therefore, quite like after 26/11, India will continue to use diplomatic and political tools to raise the costs for Pakistan.

But the former National Security Advisor, Shivshankar Menon, who defended the policy of restraint after 26/11, himself admits that “it will be virtually impossible for any government of India to make the same choice again” in the event of another spectacular attack.

The response will therefore have to be multi-pronged. While diplomatic and political instruments will certainly be brought into play, India must also start using economic levers to inflict punishment on Pakistan. These measures will have to be accompanied by some kind of kinetic action, not just to ‘assuage public sentiment’, but also to unsettle Pakistan by introducing an element of uncertainty and unpredictability in how India will respond to Pakistani provocation.

One template of kinetic action is of course the ‘surgical strikes’ carried out in September 2016. But such action doesn’t necessarily have to remain limited to cross-border punitive raids. The armed forces have worked out various options which can be exercised- options that take into consideration the possible dangers of escalation- possibly a greater threat for Pakistan than it is for India. The idea is to ensure Pakistan no longer thinks it can export terrorism to India with impunity and without consequences.

— Sushant Sareen is Senior Fellow, Observer Research Foundation