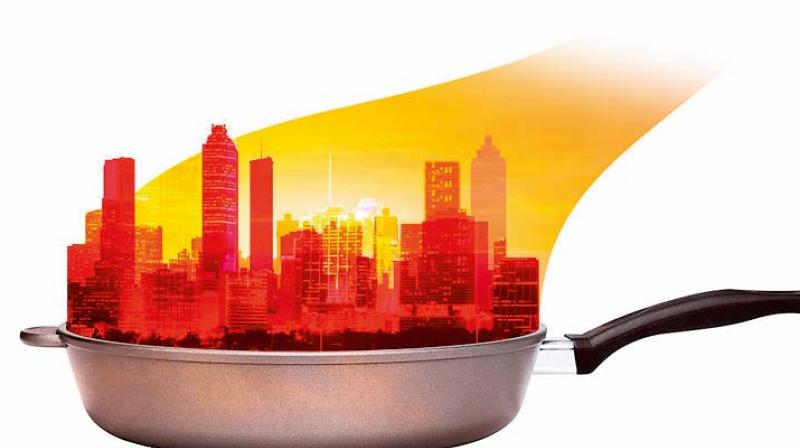

Cry for greenery: Urban heat islands could sap us

Life in cities could get more stressful as burgeoning heat islands are driving mercury levels upward even at night.

By 2030, India is expected to be the fastest urbanising country in the world. How sustainable is this growth?

We read daily reports of cities struggling under the onslaught of heatwaves and increasingly erratic rainfall. Urban heat islands contribute to both of these factors. Urban heat islands are pockets of urban concreted cover, which trap the sun’s heat during the day and retain it for long periods of time even at night. This is the reason cities tend to be much hotter than their surroundings. Of course, this has a lot to do with greenery and moisture. Cities which have retained or even increased their green cover, and protected their lakes and other water bodies, will not suffer from urban heat island effects that are as severe as other cities which are featureless expanses of concrete high-rises.

How severe can urban heat island effects be? Our research in Bengaluru has shown that tree shade can reduce midday ambient air temperatures by as much as 5°C, and road asphalt temperatures by an astounding 19°C. This has larger impact on sustainability. A city where the road asphalt is hotter by 19°C is a city where people would prefer to stay off the road, and move from more sustainable ways of transport such as walking and cycling, to using air-conditioned cars: contributing further to our already smog-filled cities.

Vegetation can play a major role in urban cooling across India. A recent paper in the journal Scientific Reports from a team from IIT Mumbai, led by Prof. Subimal Ghosh, looked at changes in temperature across 84 Indian cities using satellite data. Their findings were very interesting.

In peak summer, many Indian cities (especially in central India and the Gangetic basin, i.e. the hottest parts of the country) were actually cooler in the day than the suburban areas around: because these cities had a good canopy of green trees, while the suburban agricultural area around the cities was barren and devoid of trees. Well-planned efforts at tree plantation can actually make the environment more bearable and liveable in cities compared to rural areas.

This effect, however, is reversed at night: because the concrete in cities trapped heat, cities were hotter at night than the areas around.

Research on New Delhi by Dr Chhemendra Sharma and team from CSIR-NPL, published in Sustainable Cities and Society, showed that the city experienced urban heat island effects of 0.2-3°C in different areas. Such differences could raise the demand for air-conditioning by close to 2,000 GWh (gigawatt hours), leading to large increases in the city’s CO2 emissions (which contribute to climate change and global warming).

A recent global analysis of the world’s 1,692 largest cities (by a multi-country group of scientists led by Francisco Estrada from Mexico, published last week in Nature Climate Change) show that 60 per cent of the world’s urban population, have already experienced twice as much warming because of urban heat islands as the rest of the world, because of climate change. This disproportionate influence of cities is only going to increase over time.

We need aggressive action on a war-footing to plant trees, and restore urban water bodies, to combat these effects — across all Indian cities.

(Harini Nagendra is a Professor of Sustainability at Azim Premji University, and the author of Nature in the City: Bengaluru in the Past, Present and Future)