Biodiversity: Making world a better place

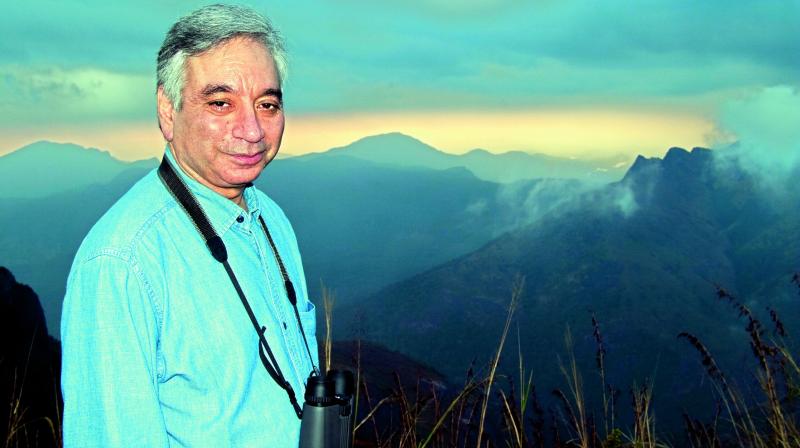

The vast pool of plants, animals and ecosystems can save India from ecological disaster, says Prof. Kamaljit Bawa.

For someone who grew up in Kapurthala, amid the dusty plains of Punjab, biodiversity was in the realm of the unknown. So when he boarded the toy train from Siliguri to Darjeeling in May 1962, little did Prof. Kamaljit Bawa, then a young research scholar, realise that the slow ride through the forests of Eastern Himalayas, a biodiversity hotspot, would be the beginning of a long journey replete with discoveries in biological sciences: A variety of tropical habitats, the impact of climate change and change in use of land on rural communities in the mountains, among others.

These discoveries have paid rich dividends in the form of a slew of awards from across the world. The latest, the coveted Linnean Medal, signals his position on a high pedestal as the first Indian to receive the medal named after Carl Linnaeus, one of the greatest students of natural history, from a society named after him. Sir J.D. Hooker, a contemporary and friend of the legendary Dr Charles Darwin, was the first recipient of this medal.

“I grew up reading and admiring Hooker’s work,” says Prof. Bawa about the first recipient of the medal, who incidentally commenced his career with research on plants of Sikkim in the Eastern Himalayas. A Fellow of the Royal Society, London, Prof. Bawa shuttles between Boston (Distinguished Professor of Biology, University of Massachussets), and Bengaluru (President of Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment or ATREE). His colleagues and he could well have a lasting solution to mitigate the impact of climate change, change in use of land, and human-wildlife conflict in mountain regions. To begin with, they are focusing on addressing these problems in the Eastern Himalayas.

“The focus is on 30 villages or almost half the villages around two conservation areas, Senchal Wildlife Sanc-tuary, and Singhalila National Park in the Darjeeling district. Each village has 30-50 households. Thus the number of direct beneficiaries is 1,500. ATREE has sought the engagement of several government agencies such as the departments of forests, agriculture, and tourism. The project is currently being supported by a grant from USAID,” he explained about the initiative aimed at diversifying rural livelihoods, integrating climate mitigation strategies with government programmes, improving soil management, along with knitting together a team of stakeholders in the region.

Prof. Bawa’s single lament: In biological sciences, the emphasis in India has been on molecular and cellular biology and biotechnology, and not on the study of life at the level of organisms, populations, species or ecological communities and ecosystems. Centres of biodiversity science in academic institutions are almost non-existent. “We have severe constraints in generating the knowledge we need to address the biodiversity crisis. For the same reason, we lack sufficient human resources to meet conservation challenges. New biodiversity science is taking shape across the world, focused on the intimate interweaving of nature with human societies. India has not been, but must be, at the forefront of this emerging science, because nowhere on Earth are natural and human systems tied together more inextricably than on the subcontinent,” he added.