STEM the gender gap

Despite recent progress, the gender gap appears likely to persist for generations, particularly in computer science, physics, and maths.

Women comprise a minority of the science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) workforce across the world. But, despite recent progress, the gender gap appears likely to persist for generations, particularly in computer science, physics, and maths.

Women are no less indispensable: Dr Sneha Sudha Komath

A World Economic Forum report highlights the ‘gender equality paradox, that as countries become wealthier and have a higher index of gender equality, women are less likely to get STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) degrees. Researchers found across-the-board phenomenon of boys’ excelling in science or math while the forte of girls remained reading.

The report quotes Dr David Geary, professor of psychological sciences in the University of Missouri’s College of Arts and Science saying that these respective boy-girl personal strengths have contributed to the persistent STEM gender difference over the years.

Dr Geary’s basic argument was that in more liberal and wealthy countries, personal preferences are more strongly expressed.

As a social and cultural construct, gender shapes our private and community lives. It also structures our institutions, including those of higher learning. An asymmetric reality is produced as a result of systematic exclusion. A brief glance at the contemporary history of women and science education in the Indian context would help elaborate this point.

Soon after independence, the Government of India set up the University Education Commission to examine, among other things, ‘the aims and objects of university education and research in India’. The Commission’s Report (1950) had an entire section on Women’s Education. It began loftily,

“...Women should share with men the life and thought and interests of the times. They are fitted to carry the same academic work as men, with no less thoroughness and quality”.

However, its recommendations were explicitly biased. It identified “some fields of work peculiarly appropriate to women”. These were, predictably, home economics, nursing, teaching and the fine arts. Thus, the thrust on women as homemakers and caregivers was explicitly underlined.

The change began with the Kothari Commission’s (1964-66) recommendations, which advocated the need for special efforts to encourage women to study the Sciences at par with men.

Yet leading universities and colleges continue to make undergraduate arts and humanities more “accessible” to women than the sciences even today.

For instance, Delhi University offers undergraduate programmes in sociology and psychology almost exclusively in women’s colleges while offering undergraduate programmes of physics in only five of the 22 such colleges.

The Mahila Maha Vidyalaya case at the Banaras Hindu University has even reached the Supreme Court. Their petition complains that hostel rules do not permit women residents to go out after 8 pm even to attend a programme or use the library within BHU campus. It also does not permit them access to free Wi-Fi/ internet in hostels or telephone/ mobile phone calls after 10 pm. In short, women in Indian science begin the race all trussed up. These biases and challenges follow them to their work places too.

The Department of Science and Technology set up a National Task Force for Women in Science in 2005. These efforts brought the issues of Women in Science to the fore, and helped identify gaps between enrolments and hiring, the so-called “leaky pipe syndrome”, problems in recruitment procedures, the double burden of women in traditional household arrangements and their absence at senior levels or in decision-making positions.

The easiest to implement were of course the fellowship schemes that did not in any way challenge the status quo. Take for instance the Depart-ment of Science and Technology’s Women Scientist scheme. This well-intentioned programme was meant to help women PhD-holders return to scientific research after a career break. But without a long-term plan to provide regular employment avenues to beneficiaries, most such schemes merely became post-doctoral fellowships with uncertain futures.

Unfortunately, funding schemes are often announced from the top. There is little cross-talk between organisations or frank assessments of previous initiatives. There is also little discussion with stakeholders. So we continue to roll out short-term solutions to entrenched problems that are bound to fail.

I have rarely, if at all, seen recommendations from any workshop adopted in an organisation and followed up over the years to assess how successful such interventions have been. The consequence?

Most organisations/departments even in the biological sciences, where the gender gap in PhD enrolments has been reversed for several years now, have only 25 per cent female faculty on an average.

Few organisations openly advocate policies to recruit women into faculty positions, or announce flexi-timings or support preferential housing. Such entrenched biases are not typical to India. It is a global phenomenon.

Here is what the World Bank Report states: 'Ingrained biases start at an early age and become even more pronounced as girls move through school and enter into the world of work...”

A survey conducted in 2010 on 568 women and 226 men scientists by the Indian Academy of Science along with the National Institute of Advanced Studies showed that not only are women committed to their careers, often they work harder than men with 46.8 per cent women spending 40-60 hours a week in the lab as compared to 33.5 per cent men. This despite the fact that, as expected in the Indian scenario and indeed in most other parts of the world, a large majority of these women were married and lived with their families.

Caregiving, whether for children or the elderly, continued to be largely their responsibility and few science institutions had put in place viable supporting structures such as quality creches or safe transport. Instead of offering flexi-timings many institutions have introduced rigid attendance rules, including Aadhaar-linked biometrics in recent times. The question however is not simply of productivity. It ought to be seen primarily as that of parity and fairness, of women being equal to men and their dignity as citizens.

Even when their numbers grow in the science academy their representations in positions of leadership remain decimal. They do not become role models for the younger generation of women and men entering science.

The prestigious science academies and awards remain elusive for women scientists. For example, every year new fellows are added to the academies by a process of election from a list of nominees. In 2017, the fraction of female INSA fellows of mathematics increased from 7.6 per cent to 8.6 per cent; in physics it fell from 4.5 per cent to 4.3 per cent, in chemistry from 1.5 per cent to 1.4 per cent, in the plant and animal sciences from 1.5 per cent to 1.4 per cent. In the health sciences alone it crossed the 25 per cent mark by 0.2 per cent. Up until 2016, 16 of the 525 recipients (3.04 per cent) of the Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar Award were women. By 2017 this was 16 out of 547 recipients (2.93 per cent). The way it is structured, this is a catch-up game that women scientists cannot win.

Quite like the corporate economy, the scientific establishment works via networks and most women do not have access to the “old-boy networks”. It is well-known that hiring, elections, nominations, awards, all are helped by such networks. Yet the issue is more fundamental. How seriously do we seek a resonance between our words and deeds?

(The author is Professor at the School of Life Sciences, JNU, New Delhi)

Fact-file

Research by Dr Luke Holman, senior lecturer, University of Melbourne, in PLOS Biology shows difficult-to-bridge gender gap in STEM, based on data of 36 million authors of more than 10 million articles published in 6,000 scientific journals over the past 15 years. Almost every field of STEM is currently moving towards a 50:50 gender ratio. Women are increasingly working in male-biased fields like physics (currently 17% women), and men are increasingly working in female-biased fields such as nursing (75% women).

The bad news: Data predict that it will take more than 200 years before there are equal numbers of men and women working in senior roles in physics, given current trends.

Other disciplines that are unlikely to reach gender parity any time soon include nursing (320 years, for men to catch up), computer science (280 years), mathematics (60 years) and surgery (52 years).

In India, a long way to go: Dr Shewli Kumar

A recent study by Unesco Institute of Statistics shows that women are missing from the ranks of higher education and research. According to the report, almost 53 per cent of women are studying till postgraduate level, but they do not progress further towards doctoral research and science education. The drop is more marked with regard to South Asia (including India) and West Asia, with only 19 per cent of women in research. In India 37 per cent of doctorates are PhD holders but only 13 per cent hold science faculty positions. This reiterates the fact that India has been particularly gender blind when it comes to fostering science education among women and that it still remains a male bastion.

Historically there have been several eminent women scientists such as Anandibai Joshi and Rukhmabai, both medical doctors, Janaki Ammal, who headed the Botanical Survey of India in the 1950s, Kamala Sohonie, a leading biochemist of her time, Anna Mani, Deputy General Director of the Indian Meteorological Department for seven years, and Rajeshwari Chatterjee, first female engineer from Karnataka, to name a few. But their names and work are not generally known to the public. Only scientists like C.V. Raman and others continue to be quoted and referred to as eminent scientists. This is an explicit indicator of the prevalence of patriarchy and male supremacy in the world of scientific research in India.

STEM the gender gap

STEM the gender gap

It is also a matter of concern as to what kind of classroom transactions, texts and curriculum are used in school education to foster curiosity in science and technology among girls. An analysis of texts used in Indian schools will show that it is usually men who are portrayed as engineers, doctors, scientists and other professionals, whereas women are projected as mothers, nurses, school teachers, housekeepers and other such nurturing professions. Girls do not get to know of alternative reference role models who will inspire scientific enquiry. At home and in society they are subjected to gendered norms which give primacy to nurturing roles and aspirations. The overall environment therefore does not encourage them to explore science, mathematics and technology.

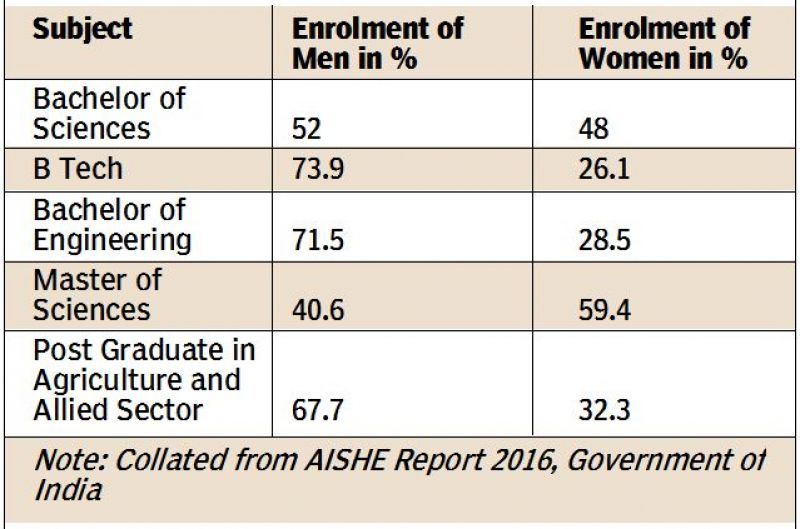

Disparities in the educational system in India and unevenness of the quality of education ensure that the outreach is limited to the upper and middle-class strata of society. The middle classes have evolved over the years, using benefits of the educational system. Their perception of status is dictated by a socio-psychological underpinning of education and professional development among both genders. Hence families from middle class backgrounds, especially in urban areas, encourage their daughters to take up higher education and research positions. On the other hand, a majority of working women form part of the unorganised sector in India — about 90 per cent (National Sample Survey 61st round). These women are largely poor and belong to lower caste and class. This class difference is reflected in the presence of women in the STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) world. A large segment of women from poor caste and class do not reach the levels of higher education and tend to drop out of education during schooling. The following table gives the span of gender wise disparity in higher educational enrolment in science and technology streams.

The data above show that women scientists and technologists have been able to break into several male bastions but they still remain a minority. For scientific enquiry and learning the milieu of education is not limited to classroom and laboratory experiments. There is a constant discourse between peers and faculty as advisors to the learning process and informal discussions in spaces other than the classroom. Also, there is considerable sexism prevalent in these institutions which acts as a deterrent for women students and faculty and often sexual harassment leads to dropping out of courses and workspaces.

Dialogues like “Now she is married and will have children, we will have to bear the burden of her work here”, are quite commonplace. This is combined with a societal and familial pressure that a woman’s primary role is that of a mother and caregiver; hence she should not prioritise professional growth over this role.

In a study commissioned by Niti Aayog (2016-17), out of 991 sampled respondents among currently working science professionals, there were 217 reported instances by women of refusal of a challenging work opportunity.

The factors cited were time commitment required for the job, childbirth, family opposition, change in job location and family care.

To ensure greater presence of women in STEM fields there needs to be a multi-pronged approach in India. It has to begin with affirmative action in school education for girls. Specific efforts need to be made to reduce sexism and sexual harassment in institutions of higher learning. Highlighting achievements of women scientists through awards, providing fellowships for women scholars in STEM, and women-friendly services including safety measures in institutions and workplaces will enhance participation of women.

(The writer is Associate Professor & Chairperson, GAC Centre for Women-Centred Social Work, School of Social Work, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai)