Time for rhetoric of justice

Politics has touched a new low, though the language used in political dialogue does not cause any distress to politicians. The new normal in politics does not entail a sense of morality, fairness and dignity towards political competitors, opponents and enemies. The trend is mudslinging theatrics by political actors. The language of power and wealth has on the one hand become legalistic and threatening and on the other, less humane and more animalistic. The language became procedural as political parties and leaders started interacting with competing political groups through enforcement agencies. It became legalistic, as it was asserted that civil society activists have no right to dictate to Parliament to enact pro-people laws. The language became threatening as a witch-hunt of those who were in opposition to the government began. The message was that only the pure, who have never committed a sin, have the right to point a finger at the sinner.

The language of power became dehumanised. The dominant trend in politics till recently was not to lose civility in political discourse. But those were the times. In a reply to a no-confidence motion, former prime minister Atal Behari Vajpayee took serious offence at the use of adjectives to describe his government as “incompetent, insensitive, irresponsible and brazenly corrupt”. He asserted that such language should not be used against democratically-elected governments. Now, in contrast, political leaders fall foul of each other through foul language. Arvind Kejriwal in 2012 used dalal (broker) to describe Sheila Dikshit, the then chief minister of Delhi, and labelled Arun Jaitley a “crook” during defamation proceedings. Further, rhetorical statements equating rivals and opponents with animals exposes an incapacity to manage one’s own affairs. Narendra Modi described Sonia Gandhi as a “Jersey cow” and Rahul Gandhi as her “hybrid bachhada (calf)”. Smriti Irani compared Rahul Gandhi to Chhota Bheem, a popular dwarfed cartoon character. To describe Mr Modi as a “monkey bitten by a dog”, as Arjun Modvadia, Congress leader from Gujarat, did, or to a virus called Namonitis as senior Congress leader Renuka Chowdhry did, or to call him Kutte ke bachhe ka bada bhai (elder brother of a puppy) as Samajwadi leader Azam Khan did, sends out a message that opposition to Mr Modi does not amount to harming a human being. Even Priyanka Gandhi exclaimed that BJP leaders were scampering like “panic-stricken rats”.

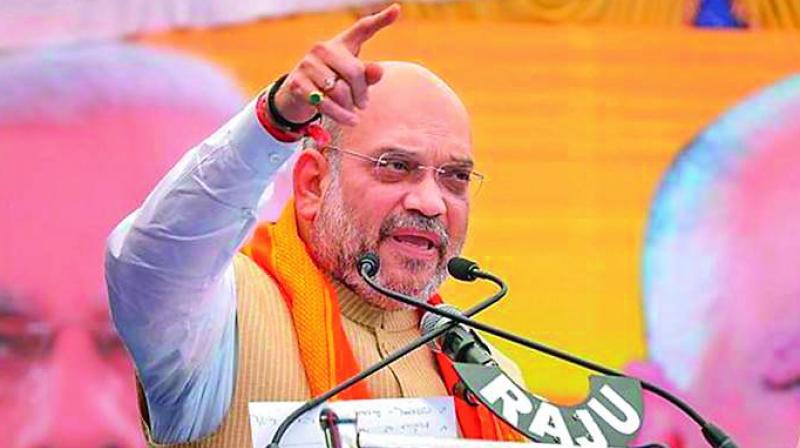

Amit Shah in a rally said, “The countdown for 2019 polls has begun. Attempts are being made for opposition unity. When huge floods occur, everything is washed away. Only a vatvriksha (banyan tree) survives and snakes, mongoose, dogs, cats and other animals climb it to save themselves from the rising waters. Due to Modi floods, all cats, dogs, snakes and mongoose are getting together to contest polls.” And Maharashtra Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis compared the opposition to “wolves”. Kailash Vijayvargiya, BJP leader from Madhya Pradesh, compared opposition unity to a “pack of dogs”. It appears that dehumanisation is emerging as a new norm in politics by introducing animal comparisons leading to marginalisation of human species. Sexism was inherent in former UP chief minister Akhilesh Yadav’s reference to BSP leader Mayawati, when he said during a joint press conference with Rahul Gandhi: “How could we have given space to her (Mayawati)? She takes so much space, even her party symbol is that of an elephant.” These animalistic expressions are a form of psychological violence against the opponent and done to hurt his/her supporters.

The sexual objectification of women leads to a disconnect with their humane, pro-people, compassionate and intellectual capabilities. And presenting enemies as anti-national is to represent them as less than human, undeserving of rights. For instance, the student protesters in Jawaharlal Nehru and Jadavpur Universities were labelled the anti-India brigade or breaking India brigade. These labels lead to the moral and political exclusion of patriotic individuals, who are fighting for justice. And those who target these individuals position themselves as saviours of the great nation. The need is to demystify this labelling lest it should lead to chaos. If people oppose globalisation, demand activation of justice systems and question the dissemination of “pre-digested knowledge and easy to understand capsules”, they are branded as undesirables against the particular notion of nationhood.

There are leaders who promise jobs to youth in a jiffy if elected; electricity tariff reduced to half if elected, and so on. But, if people protest and demand the promised bright future, they are branded anti-development. The logical consequence of this is to morally exclude a large section from fair play, compassion and justice. Therefore, the language of dehumanisation, a derivation of language of power, must be demystified and be replaced by a language of justice. Albert Camus said: “I would like to love my country and justice too”. History has witnessed that the better way to love one’s country and have pride in its greatness is to appreciate and tolerate critical ideas without dehumanising political discourse.

I remember once having been interviewed by a self-appointed custodian of Indian nationalism, a TV anchor, on the hanging of Ajmal Kasab (the terrorist captured during the attacks on Mumbai). He reprimanded me for not supporting his idea that Kasab should be hanged expeditiously rather than getting bogged down in time-consuming legal processes. He asserted that not hanging him will make India look weak in the comity of nations. In other words, the idea that countries emerge stronger by becoming justice-oriented was branded as anti-national.

(The author is Director, Institute for Development and Communica-tion, Chandi garh)