Banking on the Bard

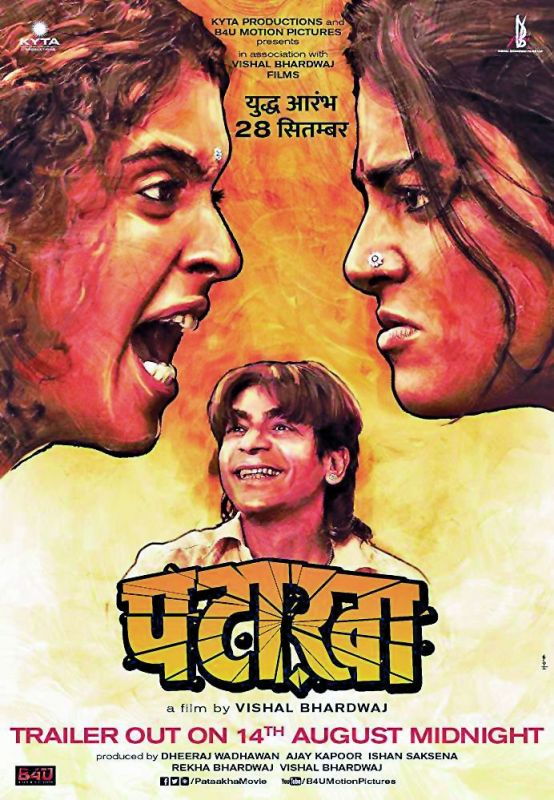

From debunking myths of witchcraft in a peculiar horror-comedy for children in Makdee (2002), to experimenting with magic realism in a story of sibling rivalry going cold in Pataakha (2018), Vishal Bhardwaj, with nearly two-decade-long career as a filmmaker, is one of the finest filmmakers of our time. His cult following gets apparent by the sight of a band of cinephiles following him at Jio MAMI Film Festival with Star, where the filmmaker has been serving in the board of trustees for a couple of years now. But before Bhardwaj would go on to invent his own vocabulary of Hindi cinema, he too was once a part of the audience of film festivalgoers – something that he is instantly reminded of every time he turns his head to look at his admirers.

In a freewheeling chat, Vishal Bhardwaj reveals the key to successful adaptations, his most challenging work and the importance of music in his movies.

“I remember the first time I attended a film festival. It was in Trivandrum (now Thiruvananthapuram) in 1996, and I did not know anything about world cinema then. For me, cinema was only whatever there was in the mainstream Bollywood then. And suddenly, at the festival, I was exposed to so many different kinds of cinema,” reminisces Bhardwaj. The broody filmmaker goes back in time, as he remembers: “ I am also reminded of Delhi because earlier International Film Festival of India (IFFI) used to happen there. I remember it would start from January 10, so it used to be so cold. We would go in a group to attend the festival for six to seven days; it brings back a lot of memories,” says the director, gripped by nostalgia.

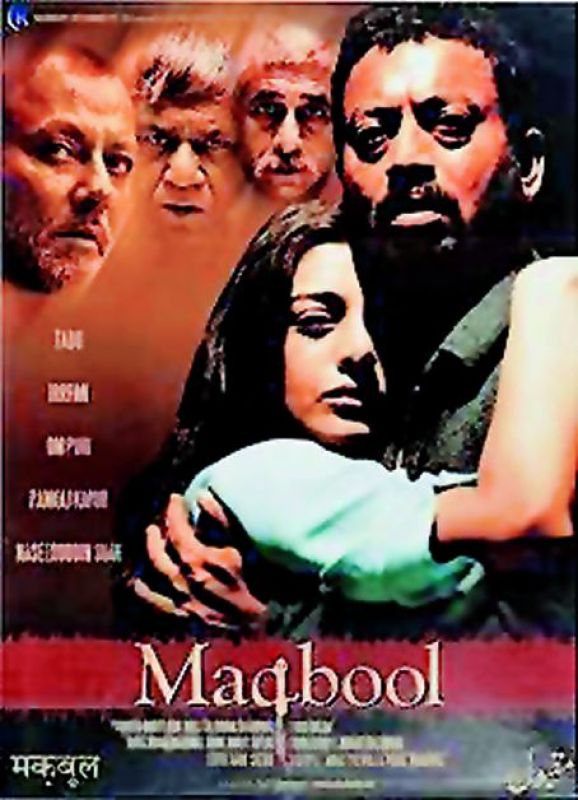

As authentic as Bhardwaj gets in his craft, it’s perchance an irony that some of his finest films have been an adaptation of tragedies by William Shakespeare. From Macbeth came Maqbool (2003), from Othello came Omkara (2006), and from Hamlet came Haider (2014). “The first time I read Shakespeare was Merchant of Venice in Class IX and then cut to Macbeth,” laughs Bhardwaj. Just like the bard himself, who was also known to adapt from texts, it’s Bhardwaj’s genius that he successfully transcreates these 16th-century plays set in Scotland, Venice, and Denmark to mafia underbellies of Mumbai, hinterlands of Uttar Pradesh and conflict-ridden Kashmir, respectively. The Kaminey director is among the few filmmakers who have been able to successfully induce the effect of catharsis in his audience similar to what one would feel after watching Shakespeare’s tragedies. So every time one sees Shahid Kapoor shouting ‘Bas ek sawaal uthata hai, sirf ek. Hum hai, ya ham nahi’ in Haider, one is instantly reminded of Hamlet’s so liloquy that begins with: ‘To be or not to be is the question?’

Talking about the key to good adept adaptations, Bhardwaj reveals, “There is a spirit behind any creative work, and it has a soul, so you have to understand that. And to me, it came instinctively. He (Shakespeare) also used sexism and racism in his work, but his plays have been really dramatic. For instance, there is a very sexist line in Omkara: ‘Joh ladki apne baap ko thug sakti hai ... woh kisi aur ki sagi kya hogi.’ It was exactly from his play Othello. So, I tried to connect to those feelings, and that’s why those emotions are translated and not just the words.” Hence, his other adaptations like 7 Khoon Maaf from Susanna’s Seven Husbands by Ruskin Bond have also been critically acclaimed, although the director reveals that the story was so strange that adapting the text for celluloid was a bit challenging. “ Rangoon was also the most difficult one to execute,” he adds.

While Bhardwaj is popularly known for his films, he actually started his career as a music composer, and still helms the musical aspect in his movies. From giving the soundtrack to his frequent collaborator and mentor Gulzar’s classic Maachis to Ram Gopal Verma’s Satya, and Vinay Shukla’s Godmother, for which he won a National Award, Bhardwaj knows how music can be used to enhance the visual experience of his audience. “Music guides your emotions. When you watch a movie, the filmmaker wants you to feel a certain way, so subtly, very subconsciously; he guides you towards that feeling that he wants you to feel. So background score does that,” he concludes when asked what’s his impetus to craft music for his films.