Is Bollywood a soft target to stir up a political controversy?

With films constantly under the scanner and public outrage playing judge and jury, can filmmakers retain their creative vision?

The web of controversies has always been wandering around Bollywood, catching one film or another. Sometimes a film manages to stir up a political controversy, or finds itself in the middle of a cast uproar, or is accused of hurting religious sentiments. An upcoming film, which finds itself in such a tangle, is Milap Jhaveri’s Satyamev Jayate. After the trailer launch, an FIR was filed against the film in Hyderabad where the complainant claimed that the film hurts the religious sentiments of the Shia community as the trailer shows the festival of Muharram followed by a scene of Matam. Not wanting to quote further controversy, the producers have decided to edit out the sequence. But film’s lead John Abraham is appalled that the film is getting a communal tinge. “I am a responsible citizen and I am showing things in a responsible way,” says John Abraham who headlines the film.

But this won’t be the first time that a film has succumbed to extraneous pressures regarding the content. Last week, Atul Manjrekar’s Fanney Khan released a song titled Mere Achhe Din Kab Aayenge, that had a dejected Anil Kapoor asking the existential question of whether life will change to better any time soon. Little did the makers know that the song would court a controversy as social media took to exploiting its lyrics to troll PM Narendra Modi’s 2014 election slogan. One thing our ruling party takes seriously is the trolls. What followed was another version of the song and a multitude of questions regarding the change. But who can blame Atul or Milap for wanting to avoid controversy regarding their films?

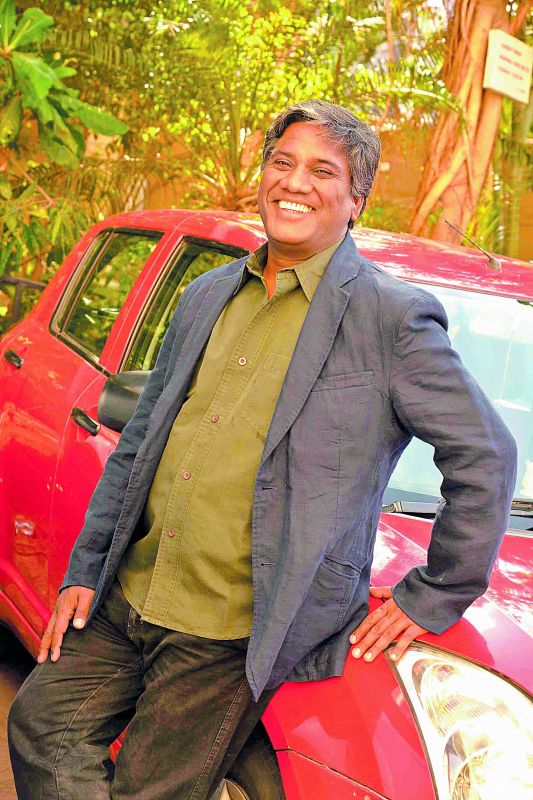

Avinash Das

Avinash Das

Avinash Das who directed Anarkali of Arah believes, “First of all, our government can’t bear political films. Even countries, which are not secular or democratic, have a tradition of making daring and demonstrative films. But we only make populist political films and any filmmaker who tries something different has to suffer for no reason,” he says. Case in point: Last year’s Tamil film Mersal which was hauled up for criticising GST and PM Modi. The end result? The makers of Mersal had to cut out a 2.5-minute sequence, even after the CBFC had cleared it. And, just this week, Mission: Impossible Fallout grabbed headlines for censoring the word Kashmir. “Censor board is unfair to us all the time but we have never stopped making films. We are still putting our points either this way or that way. If you stop this path, we will take the other way but nothing can stop us from saying what we want,” says Manoj Bajpayee adding that creativity and art will never stop. “Art will always survive and stay expressive,” he adds.

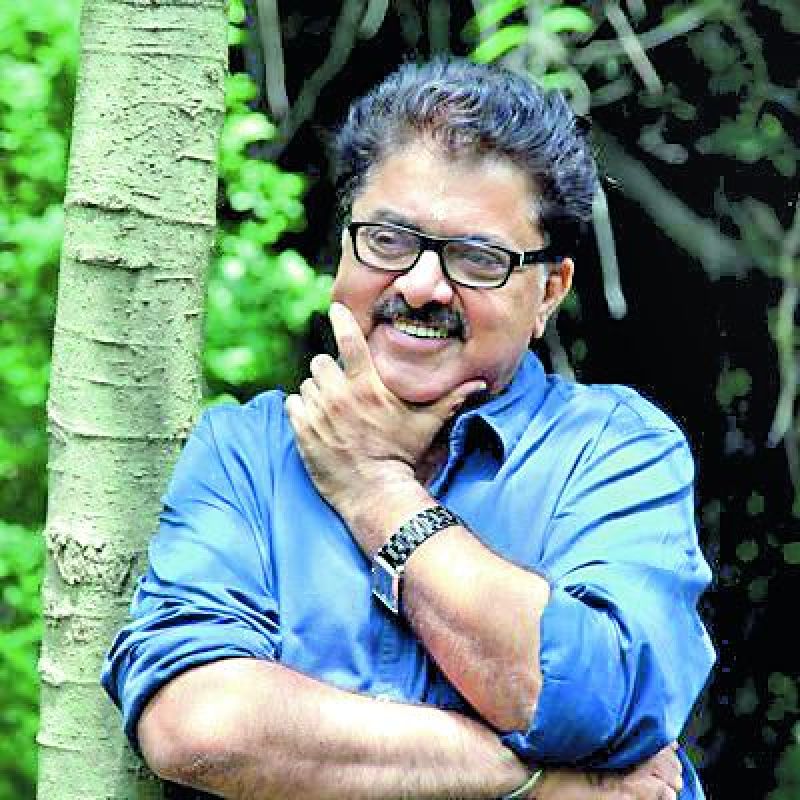

Ashoke Pandit

Ashoke Pandit

Even Bollywood heavyweight Karan Johar had to release a hostage-like video during Ae Dil Hai Mushkil endorsing the ban on Pakistani film actors and Sanjay Leela Bhansali had to re-edit parts of his film during the making of Padmaavat.

What happened to the creative freedom of speech and expression? Why is Bollywood held to ransom every time due to such political stunts? “Our

society is full of opposition and contradiction, so if someone shows them the mirror, then they are bound to feel offended. The mainstream bollywood is not able to show the mirror and those who are willing to try, face various kinds of problems. We saw what happened with Udta Punjab. Censor Board refused to give them a certificate and then the High Court had to interfere. Actually the kind of reactionary government we have, there are some groups that try to create controversy around films trying to show the truth and stop them from getting released,” says Avinash.

Talking about films becoming a soft target, filmmaker Ashoke Pandit says, “As far as films like Padmaavat are concerned, there is a political pressure. It has been happening right through the independence days. So any political party that comes to power thinks that films should be made according to their vision. Entertainment industry has always been a soft target. For instance, in Fanney Khan, the phrase ‘ache din’ has nothing to do with the country. It’s an expression in the film.” Dialogue writer Ram Kumar Singh seconds this view and asks that why it should matter if someone uses a tagline that was used for the elections? “Unless it’s your intellectual property, it should not matter. If it is on a public domain and a creative person uses it, then there shouldn’t be any controversy around it. But unfortunately it is happening and it’s not a good thing,” he says, adding that one shouldn’t always judge a film by its trailer. “It could be in a completely different context in the film depending on where it’s used and the impact it has. But intentionally, no one should hurt anyone’s religious sentiments, on the name of freedom of speech,” he says.

However, with social media and social media platforms like Facebook, Twitter and Instagram seeping into the lives of people, getting offended is nothing new. But that shouldn’t lead to freedom of speech and expression being curtailed. Ashoke also states that filmmakers should not be forced to alter their content after it has been passed by CBFC. “We will make whatever we want to make, and there is a censor board which is a government organisation which takes care of it. And if we have to go by the choices of every individual, I won’t be able to write a book, I won’t be able to make music, I won’t be able to make a film, I won’t be able to do anything,” he adds.

HT07