Book review: Allusional narrative shows wars don't win political peace

Chennai: This is not Lord Ganapathi the scribe, meticulously taking down every word of Veda Vyasa’s narration of the great epic ‘Mahabarat’, which people are largely familiar with as symbolic of an old story-telling tradition,

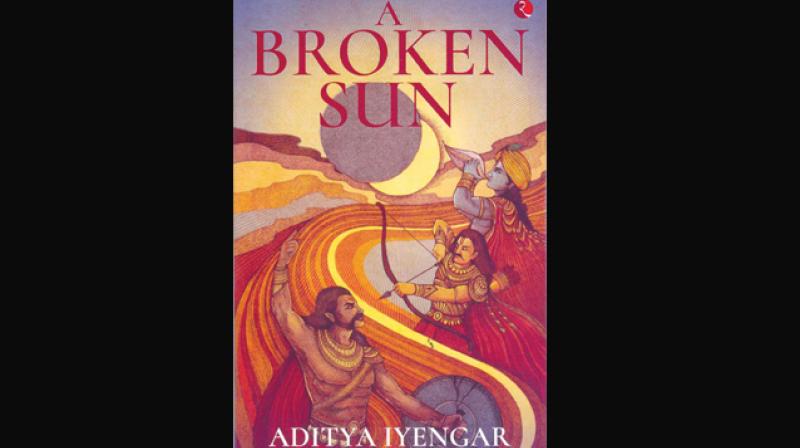

In retelling the great Epics in the digital age and in a new literary idiom that effortlessly concerts a multiplicity of voices speaking their parts within a larger canopy of minimal textual fidelity to the ‘originally heard story’, writer and advertising professional Aditya Iyengar’s latest offering, ‘A Broken Sun’, a sequel to his ‘The Thirteenth Day’ and part of a trilogy on the Kurukshetra war, has sought to break fresh interpretative grounds on the larger import of ‘Mahabarat’.

The author’s first novel weaved around the climaxing core of the staggeringly human epic and ‘repeatedly embellished’, ends with the death of Abhimanyu on the 13th day of what was the 18-day Kurukshetra war. The period of his novels as Aditya puts it, are “set around 1000 BCE, during the Iron Age in India.”

Picking up the thread from there, the second of this trilogy goes up to the ‘The Fifteenth Night’ of the war, both the fratricidal warring groups, Kauravas and the Pandavas, painfully coming to terms with the death of their ‘greatest Guru’ Dronacharya on the battlefield. A strategist and diplomat Lord Krishna in goading Bhima to weaken Drona’s indomitable will with partially misleading information, that his son “Ashwattthama is dead”, played a part in it, as it later transpires that Bhima had only killed an elephant by that name the previous day.

Drona was finally dead - in a sort of Pandavas avenging the perfidious death of Arjuna’s great warrior-son Abhimanyu - though Yudhishthira, the eldest of the Pandavas, has the intellectual honesty to tell Dhrishtadyumna, “killing a defenseless old man is as bad as killing a young one. I say this not to upset you, Dhristadyumna; your father (Guru) was truly the best of us.” Such soul-searching is not confined only to Yudhisthira, but is seen on both sides of the warring clans for the throne of Hasthinapura.

As his second novel in this trilogy draws to a close with Radheya coming to seek the ‘blessings’ of the wisest elder of the Kuru clan, Bhishma, who preferred being called Devadutta, as he is chosen to lead the Kauravas for the remaining part of the war after the death of the ‘greatest commander-in-chief’ Drona, the author a page earlier says this in the words of Arjuna: “We spend our entire lives preparing ourselves to deal with loss.”

And Arjuna still hopes to meet his dear Abhimanyu “in the next life”, even as word comes across to the battlefield tent that Abhimanyu’s widowed wife, Uttaraa has been carrying a child. Eternal recurrence!

Bhima loses his brave son too, born of his wedlock to tribal woman Hidimbi in the forest, showing how political heirs have made their alliances even in exile. When Ghatotkacha came to fight in the war on his father’s side, he was only hoping to take back Bhima to his dear mother again in the forest. But in a quirk of fate, Bhima cradles “Ghatotkacha’s dead body on a bier made of wood as a couple of men stood behind him, waiting for him to leave so that they could wash it.”

“He shouldn’t have gone, Abhimanyu and him should have stayed back with the other sons,” he sobbed loudly. ‘Bhima….Bhima…., I could only say his name to try and soothe him. I had nothing left…No words. No wisdom…..I pulled Bhima away as the tribe conducted their funeral rites…… Arjuna had become a walking ghost, a hollow husk of a human being whose only contact seemed to be with the imaginary spirit of his son.” These words the author makes Yudhishthira speak.

Aditya Iyengar’s style in this polyphonic epic-based fiction is certainly evocative, perlocutionary, compelling and graphic with details of the battlefield scenes, without losing sight of the gravitas of the greater human tragedy unfolding itself in the theatre of the Kurukshetra war. However, what seems even more significant from today’s point of view is the un-spoken, unsaid, allusions that the narrative points to. It is to the futility of any war itself.

The unbearable, putrid stench of the bodies that lie on the battlefield, many unaccounted for days, wails of the injured and maimed soldiers alongside the slain animals used in the war, what beastly shakes of men and chariots do to the soil itself, are all cyclical grim reminders that whatever may have led to the war – its often touted justification of the righteous (Dharma) winning over the evil forces (Adharma) - war is no alternative to any peaceful political settlement.

It was after all, brother killing brother! For all the mighty philosophic import of Lord Krishna’s advice to Arjuna on the battlefield, doubts still linger in the mind of Yudhishthira, towards the end of this narrative, for in the face of any crisis he becomes the rationale to justify the ‘Dharmic war’. Significantly, only later Yudhishthira hears out the ‘Vishnusahasranaama’, told by Bhishma from his ‘bed of arrows’ in the presence of Krishna himself!

Yet, the nonchalant, consummate calculations of those who seek to exercise de jure political power – not in the least Lord Krishna - once the Kingdom is theirs, seems to bother Yudhishthira a lot. He rails at Krishna: “You have been responsible for keeping me in the back. As bait for Drona. I have nearly been killed twice.” Krishna replies, “This is war, Yudhishthira, Men get killed, you’re getting paranoid.”

Yudhishthira then goes to say, as in the words of the author: “My mind was whirring with possibilities. Was Krishna trying to put a Yadava on the Kuru throne? Was he systematically planning our destruction? Or was he trying to protect us as he claimed?” “What was I thinking? Was the war playing tricks on my mind?” This seems one huge take-away from this narrative: In a nuclear world, tough trade talks still seem better and hopeful than ideologically woolly sectarian strife. Wars, by whatever name they go, hardly win political peace.