Adi Shankaracharya: From Kerala to Kedarnath

The rise of an aggressive band of self-annointed evangelists has resulted in Hinduism’s darkest hour, where ancient and profound schools of philosophy are reduced “to the lowest common denominato”, marked by violence and rigidity. Writer and former diplomat Pavan Varma, has taken it upon himself to rediscover the ancient philsophies and tells Darshana Ramdev of his journey from Kerala to Kedarnath as he retraces the glorious life of Adi Shankaracharya

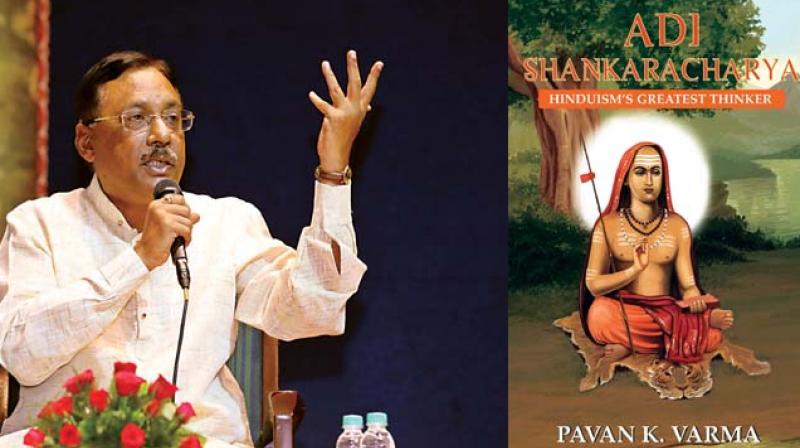

Clutching a copy of Pavan Varma's Adi Shankaracharya: Hinduism's Greatest Thinker, an image of the saint seated in Padmasana emblazoned across the cover, draws an assortment of colourful reactions. There are those who balk at the imagined tediousness of a book on philosophy, but those, perhaps, are to be expected. The current climate of political acrimony, however, elicits two major responses. One group shudders at the mere mention of title: “I would not read that.” Others, however, approach with unabashed curiosity and enthusiasm, quickly hopping in line for a chance to read it too. When Varma arrived in the city last weekend, he found, to his delight, a profusion of the latter, for he found himself signing books late into the night.

Today, Hinduism is widely reduced to the aggressive tenets of the Hindutva, with self-appointed protectors who ultimately trivialise the very religion they set out celebrate. “I am no subscriber to the Dina Nath Batra school of thought,” Varma proclaims. “Hinduism has grown through logic and shastrar (dialogic engagement). Today, it is reduced to its lowest common denominator, with ritual taking precedence over philosophical thought.”

Adi Shankaracharya was born in Kerala, where he soon manifested prodigious accomplishment in scholarship. He could recite, even as a child, complex Sanskrit shlokas and vachanas beyond the grasp of many an older, more experienced scholar. By the time he was a teenager, he knew his calling lay in asceticism and set out, having bid goodbye with a heavy heart to his grief-stricken mother, in search of samadhi. This he found in Kedarnath, a trail that Varma took too, meeting along the way, a medley of scholars, lovers of philosophy and priests who established, implicitly and otherwise, the importance of Hinduism as an “edifice of thought,” a subject of endless debate. One merits mention: Maroof Shah, a scholar of Kashmiri Shaivism, is a devout Muslim “who happened to be keeping the Ramzan fast' when they met.

A compelling read, the book is rife with interesting plot twists, that in the end, reflect Hinduism's origins as philosophical debate: In one anecdote, Ubhaya Bharati, the wife of Mandana Mishra, one of the guru’s greatest disciples, requests Shankara to answer questions on sensuality and eroticism. She, as a married woman, was familiar with the subject but Shankara, a sanyasin, knew nothing at all. The fantastical recounting of the story has Shankara leave his body and enter that of a dead king in the Gupteshwar cave on the banks of the Narmada. There, in the company of the dead king’s wives, he became skilled in the ways of the kama shastra, and, Varma writes, “Began to so much enjoy his new distractions... that he forgot he had to within a month, reassume his own body.” The debate, he proceeds to explain, “was to assert the primacy of thought over ritual, at a time when precisely the opposite seemed to have become the accepted way of life for Hindus.”

The Hinduism Varma attempts to expostulate is one he calls “an edifice of thought unmatched in its profundity, seeking to provide the ultimate answers to the ultimate question.” Pavan Varma's exploration of the remarkable life of Adi Shankaracharya, arguably one of Hinduism's greatest thinkers, led him to a bedrock of a philosophy that begins and ends with logic, a seamless combination of the transient and the absolute, the all-encompassing ‘non-duality’ in which both the practical and the transcendental have their rightful place.

“I was amazed,” he admitted, after the roaring success of his book launch in Bengaluru. “Clearly, people want to understand the philosphy over and beyond what is presented to them.” The book is extensively researched, Varma has left no stone unturned in his search for details of the great thinker's life. He found, along the way, that much had been preserved in myth, very little through actual history, somewhat reminiscent, perhaps, of the Puranic method of preserving and simplifying complex philosophical truths through storytelling. The debates, he writes, were rigorous and mentions, with a slight hint of humour his own experience within a temple. During one debate, he learned, a scholar was so angered by the opinion of his rival that when he attempted a rebuttal, he died of a heart attack. It must be said at this juncture that Shankaracharya saw knowledge as a means to enlightenment, giving empirical wisdom its rightful place in the spiritual journey but emphasising that it cannot stand on its own “Worship

Govinda, foolish one! Rules of grammar profit nothing once the hour of death draws nigh!”

Compelled by his own research on the cosmos and a growing need to reclaim Hinduism from its “evangelicists,” Varma found that Shankara’s ideas, born as they were in philosophical thought, are finding affirmation now, in modern science. “Einstein, Schrodinger, Maxwell, have produced scientific theories that affirm the advaita philosophy, the presence of Brahm or the eternal, infinite, indivisible and formless truth, the ultimate intelligence.” Adi Shankaracharya brought the tenets of Hinduism together, linking wisdom with ritual, truth with metaphor, the real with the ephemeral. Could Brahm then be described as a combination of the permanent (bimba) and its worldly reflecton (pratibimba)? Shankaracharya, Varma writes, candidly said that Brahm is beyond all understanding and articulation, beyond cause and effect.

In the end, one returns, with an inexplicable sense of lightness despite the ponderous nature of the book itself, to the Nasadiya Sukta, or the Hymn of Creation, contained within the Rig Veda: “Whence all creation had its origin, he, whether he fashioned it or whether he did not, he, who surveys it all from highest heaven, he knows - or maybe even he does not know,” Pavan Varma describes it with finesse too, flowing effortlessly between English and Sanskrit to sum up (if one could presume to do so) what is perhaps, one of the most complex schools of philosophy. 'Ek dum sadhya bahudha vadanthi' (the truth is one but the wives call it by different names).