Book review: A candid account of bifurcation

Jairam Ramesh sent me a copy of his book on the bifurcation of united Andhra Pradesh and the creation of Telangana, with a text message: “Trash it, but read it”. I instantly replied: “The people of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana have trashed and thrashed your party, so now why should I trash your book?” He replied with a smiley. One of the best consequences of the ignominious defeat of the “Sonia Congress” in the Lok Sabha elections of 2014 has been that Jairam Ramesh has found time to write books. This is his third. He writes well and is always a pleasure to read. I have not read his book on India’s policy on climate change and global warming, but I did read his book on his three months in P.V. Narasimha Rao’s PMO and the crafting of what I have termed, “Narasimhanomics” — the new economic policies of PV.

Both books are useful contributions to the literature on public policy. My only complaint about the book on 1991 reforms is that it gives undeserved credit to Rajiv Gandhi, who shied away from implementing the policies that Rao did, even though he had over 400 MPs in Lok Sabha and Rao had less than 240. It also gives the impression that Rao’s only role was to implement policies that others had thought of. Jairam is too clever a politician not to recognise the importance of political leadership in heralding policy change. Rao had the wisdom and courage needed to implement radically new policies — both on the economic and foreign policy front. Rajiv did not.

In fact, the book on Andhra Pradesh bifurcation offers a good contrast to the book on 1991. If in 1991, the political wisdom and experience of Narasimha Rao enabled India to weather many storms, in 2012-14 period the complete lack of political wisdom on the part of the “Sonia Congress” and the Manmohan Singh government created a mighty mess in undivided Andhra Pradesh. The problem was not with why the decision was taken but how it was taken and finally implemented. As Jairam himself admits, people in both Andhra Pradesh and Telangana were unhappy with the A.P. Reorganisation Act 2014.

The “Sonia Congress” was paralysed by incompetence and Andhra Pradesh was caught in an avoidable storm. I say avoidable because by 2013 it had become clear to anyone who cared to understand the facts that the bifurcation of the state had to happen. All political parties, save the communists, were officially in favour of bifurcation. On the other hand, both the Telugu Desam and the Congress Party faced strong internal dissent. The political challenge for the Congress, as the ruling party in Delhi and Hyderabad, was to manage this dissent within and arrive at an amicable settlelment. It failed to do so.

Jairam’s book offers us a good account of the process of bifurcation but it fails to explain why the process was so messy and why, at the end of it, the people of both Andhra Pradesh and Telangana felt betrayed by the “Sonia Congress” and “trashed and thrashed” the party. Jairam is candid and honest when he says that the Congress expected the Telangana Rashtra Samithi (TRS) to dissolve itself and merge with the Sonia Congress, a la Dr Marri Chenna Reddy’s Telangana Praja Samithi (TPR) merger with the “Indira Congress” in 1971.

But that happened when Indira Gandhi was at the height of her power. Moreover, Reddy was a lifelong Congressman. TRS’ K. Chandrasekhar Rao had quit the Congress to join NTR. He had experienced the sense of freedom in a regional party. Why would he want to give that up to be a supplicant in Sonia’s Delhi darbar?

In the end, both TRS and Telugu Desam benefited from the stance they adopted by winning elections in their respective regions of influence, while the Congress lost out in both states. Jairam does not discuss what political lessons have been learnt from this experience. What the book offers is a detailed account of what happened in the final year of the second Manmohan Singh government — between October 2013 and April 2014.

Given the limited scope of the book it will be of interest to those who wish to know how bifurcation was organised. I would have liked to read Jairam’s views on what political lessons have been learnt by the Congress. Perhaps none yet, given the fact that senior Congress leaders in both Andhra Pradesh and Telangana continue to leave the party to join the respective ruling parties in both states. I hope Jairam’s next book will be about the lessons that the Congress has learnt or has to learn from its declining fortunes.

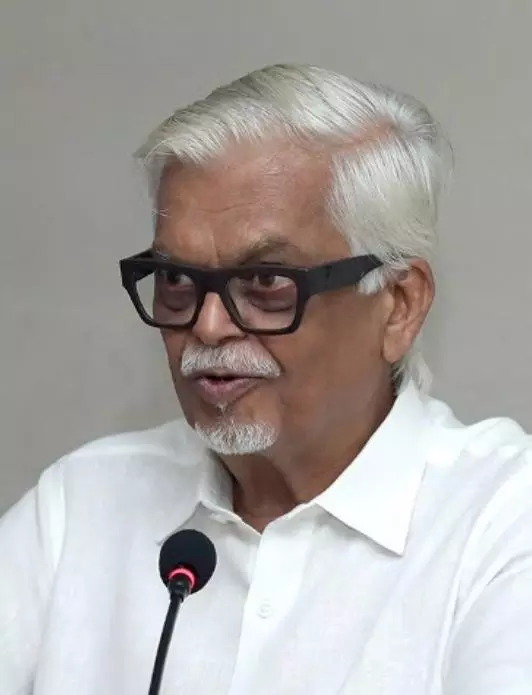

Sanjaya Baru is the author of The Accidental Prime Minister: The Making and Unmaking of Manmohan Singh