Concise and robust political narrative on Jayalalithaa Jayaram

But having brought down the Vajpayee government, Jayalalithaa found herself nowhere and without friends.

Chennai: Former Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee, who precisely knew in which part of the country his Cabinet colleagues were for the day and for what purpose, nonetheless, had no clue that the Ides of March would strike his regime in 1999, 13 months after he was heading an NDA government at the Centre.

The by now famous ‘tea party’, hosted by Dr Subramanian Swamy to the Congress President Sonia Gandhi and the All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) supremo J. Jayalalithaa, in New Delhi turned out to be the ‘political earthquake’ of March-April 1999, as the latter called it, leading to her party withdrawing support to the BJP-led NDA then and Vajpayee losing his government by one vote.

Even before the ‘tea party’, Ms. Jayalalithaa’s relationship with the BJP had taken a nosedive, for the then Prime Minister “was not willing to oblige” the many demands that she had placed, including her expectation that the “Centre would get her out of her court cases.” For she assertively pursued the logic that, after striking a deal with the BJP in the Lok Sabha polls in 1998, it was she (Jayalalithaa) who took Vajapyee’s name to every nook and corner of Tamil Nadu, that helped NDA to form a government in New Delhi, with a significant contribution to the Lok Sabha numbers coming from Tamil Nadu.

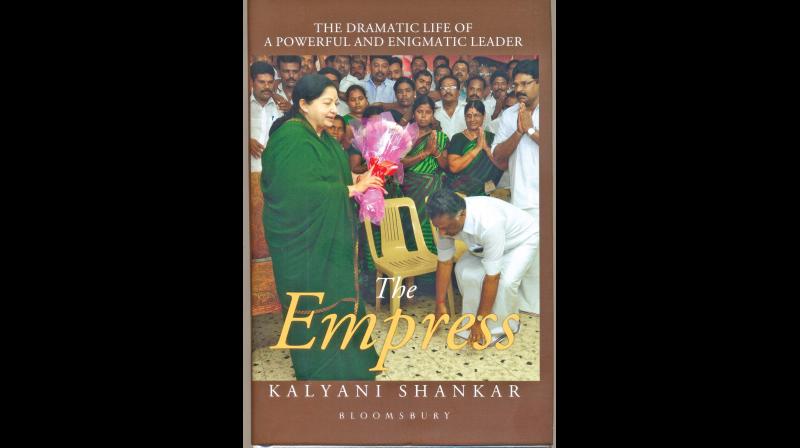

But having brought down the Vajpayee government, Jayalalithaa “found herself nowhere and without friends, because she fell out even with the Congress,” writes the veteran journalist and political columnist, Kalyani Shankar, in her latest book ‘The Empress: The Dramatic Life Of A Powerful and Enigmatic Leader’. Quoting Dr Swamy, who “was the main player in the whole drama,” the author writes: “For me, it was a full adventure. I had to do only one thing – to pull down the Vajpayee government. But for Jaya it was sad. If she had left it to me (handling the fallout), I would have done it better. But once we brought down the government, she said T.T.V. Dhinakaran (AIADMK MP and V.K. Sasikala (her confidante)’s nephew and herself would handle it.

They made a mess of things. As for her Prime Ministerial ambitions, she never told me, but at one stage she did tell Mulayam Singh that he should support her. West Bengal Chief Minister Jyoti Basu told me that when she had come and tried to persuade him to accept Prime Ministership, he said jokingly, ‘You are there’. He said she had taken it seriously and she went and told Mulayam. He (Basu) asked me (Dr Swamy) to correct her impression, since he had not meant it seriously. But I had no heart to tell her.” And to her utter discomfort, DMK, which backed Vajpayee in the confidence vote, almost instantly joined the BJP-led NDA.

Again later in the book, the author draws attention to how the corridors of power in Delhi even in 1999, was agog with allegations of how Sasikala was also instrumental in Jayalalithaa joining hands to bring down the Vajpayee government, as the BJP managers in Delhi had then “sidelined” Sasikala, “a woman whom she (Jaya) called her sister and also her alter ego.” “Sasikala was little heard and hardly seen, but she became powerful in the party and government affairs,” says the author in her chapter on ‘Sasikala takes over’ after Jayalaithaa’s sudden death on December 5, 2016, a game-changing moment.

Seen in this backdrop, after Amma’s demise, it thus comes as no surprise that Sasikala and Dhinakaran continue to be key figures in the bitter internal turf war within the party in claiming the combined MGR-Jayalalithaa legacy now. Though Ms. Jayalalithaa, like the legendary M.G. Ramachandran, did not name anybody as her successor or her political heir, the 1999 developments seem sufficient pointers to who mattered more than other leaders in the AIADMK’s pecking order. It also in part explains the current ruling BJP’s dispensation’s plain animosity towards Ms. Sasikala and her close kin.

It is the weaving in of such credible anecdotal information and insights gleaned from a rich variety of sources including the US Embassy’s cables to their HQ that were brought to light by ‘Wikileaks’, and the author’s personal interviews with range of contemporary leaders including Dr Swamy, S. Thirunavukkarasar, former Governor Bhishma Narayan Singh and former Prime Minister P.V. Narasimha Rao, who all had either known or interacted with Ms. Jayalalithaa at some point of time, which brings out the wider significance of the political power-play that she was embroiled in for nearly three decades, ever since she took over the party’s leadership after her mentor MGR’s death.

While the few biographies on Ms. Jayalalithaa that have been published in the last year or so have focused more on her personal life and on her transition from a charming and versatile film artiste to becoming a ‘Queen’ in politics as well, Kalyanai Shankar’s succinctly structured book comes out as a straight, candid and a more robust political narrative of an astounding Chief Minister who went on to make a huge national impact.

Whether it was fighting for the State’s rights in issues such as Cauvery, clamping down on the LTTE after former Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi’s assassination on Tamil Nadu soil, unflinchingly flagging huge revenue losses for manufacturing states like Tamil Nadu in opposing the Goods and Services Tax, or being seen as a Prime Ministerial prospect, the author seeks to drive home how Jayalalithaa, for all her tough and autocratic ways, went down as a fighter, redrawing the boundaries of women’s leadership in politics in post-Independent India, even if she had lost some of her electoral and legal battles.

That Tamil Nadu polity appears to have lost the comfort zone of a well-established two-party (DMK/ AIADMK) political system after Ms Jayalalithaa’s abrupt demise is a key takeaway from Kalyani Shankar’s political biography, which the author ends poetically: “She was an empress when alive, and is certainly an empress in death.” Quite a few printer’s devils in names and dates would hopefully be corrected in the next edition.