From Bengal to Banaras: The eye that feels

This Parekh has explored through a varied and colourful career.

“The saree and the lungi are the only two forms of unstitched attire in the world,” the artist Manu Parekh declares, a large smile lighting up his face at the thought. “Do you realise that? Do you? No, do you?” he demands, until one can’t help but smile also. He brings it up again the next day, over the phone: “I was thinking about what I told you yesterday, about the saree and the lungi and it makes me so happy! Why don’t people think about these things too?” The artist, who won the Padma Shri in 1991, is a rare beacon of hope and positivity in the artist’s world, one that modern schools have sought to cast into shadow, turmoil and the mire of socio-politics. “We talk about the bad, but never the good. Why see one side and not the other?”

The city of Calcutta, “Which I have now left,” Parekh remarks, somewhat ruefully, once served as his muse. Now, it is the city of Benaras, home of the faithful. The bustle and the apparent chaos of a city where the ancient and modern form their unruly juxtaposition, is to Parekh, a great fount of authenticity and spiritual celebration. “Even as a child, I enjoyed the celebrations that surrounded a particular religious festival, even though I wasn’t really captured by the spirituality of it.” And aside from his references to Klee and Tagore, Manu Parekh speaks with the utmost simplicity: “I don’t seek to impress you,” he says, the geniality in his eyes replaced by a steely glint.

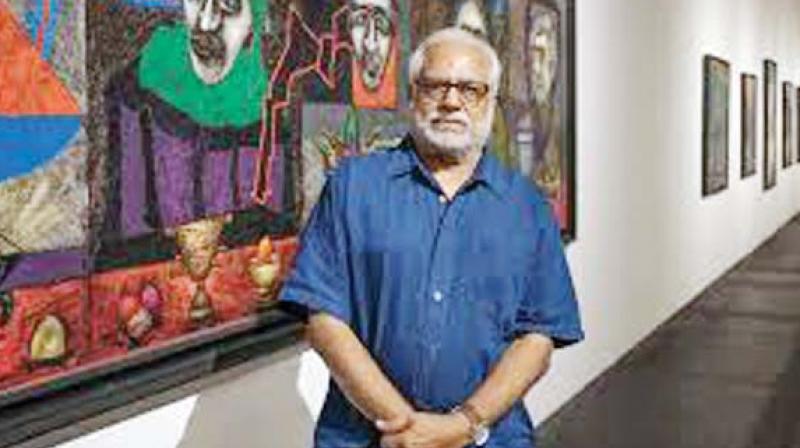

Dressed in his trademark printed shirt and faded jeans, Manu Parekh is in the midst of a hands-on effort to set up his show at the NGMA Bengaluru, three days before its opening. The quiet of the gardens is boldly contradicted by the volley of activity within the gallery itself - it is a mammoth exhibition, featuring 60 years of work by the renowned artist. It includes selected works from series like Early Works, Rituals & Abstract, Animals, Still Life, Heads and Banaras Landscape, by Parekh, who is often likened F.N. Souza and Ramkinkar Baij (both of whom he considers mentors).

“I have a small complaint,” he says, as he moves towards the small wing that houses his earliest works, mainly portraits and line drawings. “It’s not a complaint so much as a wish: All art needs to be rooted. I find that missing today.” The idea of ‘rootedness’, which incidentally, produces a canopy of explanations from Parekh, has been a lifelong philosophical journey. What is rootedness, one might ask, only to receive the rather vague response: “When I say rootedness, I mean I draw from my own experiences and surroundings. Abstract work has its merits but not at the cost of this.” This doesn’t, however, mean Parekh’s work is blinkered or uni-dimensional, he pays tribute, through the subtlety of form, to the many nuances of the human experience – the phallic-shaped vase, for instance, that reappears in his still life works. “Sexuality is a celebration too, although we seem to have forgotten this,” he says.

Parekh’s earliest memories of art go back to when he was a seven year old at a village school. There, he found he had a way with a pencil and was often called upon by the teacher to demonstrate diagrams for the class. This was a matter of pride, clearly, for he laughs, “Even at that age, I was quite shrewd! I saw that art had allowed me to become a teacher for a day, I knew then I should pursue it!”

Everything changed when he arrived at the JJ School, where he discovered the philosophy of Paul Klee. “I’m greatly influenced by his pedagogy,” he remarks and the words, ‘Paul Klee’s Thinking Eye’ are among the first he utters. “The fundamental themes are always those of non-positivity, elusiveness and the uncertainty of existence,” reads a line from Thinking Eye, one that weighs greatly on Parekh’s artistic philosophy. “There is a need to fill that void by human endeavour and artistic creation.” To Parekh, the the world of art is an all-encompassing one, where every experience contributes to the nature of art.

This Parekh has explored through a varied and colourful career. Prompted by a lifelong fascination for cinema and the trips to the theatre he would make with his father, Parekh tried his hand at theatre and gave it up, reluctantly, when he found he just did’t have the time. He then spent 25 years in the handlooms industry under the legendary Pupul Jayakar. At the time, she had decided to hire only artists and Parekh succeeded K.G. Subramanyam. This took him to the rural heartlands of India, where he found his magic. “The people there are so guided by instinct,” he says. “The farmer can look at the sky and tell you, correctly, that it will rain in a week. The women are the same, so instinctive and powerful.” When one interjects, saying that this is a rather Gandhian sentiment, he professes, at once, his great admiration for the Mahatma. “Tagore and Gandhi are my heroes,” he says. Parekh visited Shantiniketan and was influenced deeply by Rabindranath Tagore. “I always read his work and he was very rooted,” he beams. This, despite the Bengal School’s preference for Western and bohemian influences.

“I have great faith in the culture and history of this nation,” he says, pausing to note that India has the highest number of successful sculptor-couples. “Do you know how many there are? There are 10. But do we think of these things? No, we think of development where it is not necessary.” So small is beautiful? “Perhaps. For instance, a group of local craftsmen who deliver their goods at a decent rate at a nearby market don’t need ‘development’. There would be no point creating online or urban markets in this case because it would simply destroy an equilibrium.”

And as the world dances before Manu Parekh’s eyes, it does so in total perfection. Here, everything has its place, the magic exists for everybody who chooses to see it. “I do use a lot of black,” he agrees, in response to an observation. “Where there is light, there is shadow, yes?”

What: Manu Parekh - 60 years of selected works

When: Till July 15

Where: National Gallery of Modern Art, Manikyavelu Mansion, Palace Road.