Our democracy lies in the freedom of our institutions

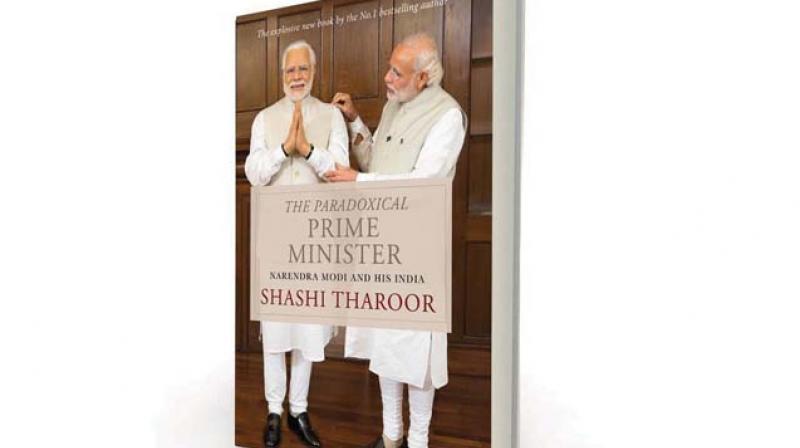

Following is an excerpt from the chapter ‘The Attack on Institutions’ from the book ‘The Paradoxical Prime Minister: Narendra Modi and His India’.

Mahatma Gandhi once said: “The truest test of a democracy is in the ability of anyone to act as he likes, so long as he does not injure the life or property of anyone else.” In order for this to happen, every institution that upholds a healthy and vibrant democracy needs to be fostered and cared for by the government of the day. The independence of these institutions needs to be protected so they are able to dispense neutral decisions in the interest of every citizen of India. A list of such institutions would include the judiciary, headed by the Supreme Court; the Election Commission, which organises, conducts and rules on the country’s general and state elections; the Reserve Bank of India, the nation’s central bank; the armed forces; the national exam-conducting bodies that test tens of millions of schoolchildren every year in highly competitive examinations that could make or break their futures; the investigative agencies (notably the Central Bureau of Investigation, India’s equivalent of the FBI); the elected legislatures; and the free press. Every one of these priceless institutions has come under threat in the last four years, as an assertive Hindu-chauvinist BJP government moves to consolidate its power in the world’s largest democracy.

The judicial system, traditionally above the cut-and-thrust of the political fray, came under withering scrutiny in January 2018, when the four senior-most judges of the Supreme Court held an unprecedented press conference to question the decisions of outgoing Chief Justice Dipak Misra in allocating cases to his favourite judges as “master of the roster” their criticism seemed to imply that this would lead to outcomes to favour the government.

Chief Justices of India are supposed to be free of political interests, but in April several Opposition parties circulated an equally unprecedented impeachment motion against the Chief Justice in the Upper House, the Rajya Sabha. Though this was rejected by the Rajya Sabha chairman, the vice-president of India, two MPs moved the Supreme Court itself to challenge his rejection, only to find the Chief Justice naming a bench favourable to him to hear their appeal. They then withdrew their case, but the image of the judiciary has taken a beating from all this, from which it will not easily recover. India’s Election Commission has also enjoyed a proud record of independence and boasts decades-long experience of conducting free and fair elections, despite its members usually being retired civil servants appointed by the government of the day for fixed tenures. While in the past, election commissioners have largely enjoyed a reputation for integrity, this took a severe blow last year, when a BJP-appointed chief violated the convention of announcing election dates for all impending state elections at the same time.

A quarter century ago, the commission had introduced a Code of Conduct that prohibits government expenditure to impress voters once election dates are announced. With the BJP, which is in power in both the Centre and in Gujarat state, scrambling to impress voters in Gujarat through last-minute schemes and pre-election freebies, it was alleged that the EC came under pressure to delay the election announcement there as long as possible.

Surprisingly, it declared the dates for elections in Himachal Pradesh, a state that normally goes to the polls at the same time as Gujarat, thirteen days before the latter, ostensibly in order to permit flood relief work in Gujarat (which the Code of Conduct would not in fact have disallowed).

Former election commissioners condemned the decision unanimously, even as the Gujarat government and the Prime Minister himself took advantage of the delay to announce a series of pre-election giveaways. It does no good to Indian democracy to see a shadow fall over the very institution that guarantees free and fair elections, especially at a time when reports of data manipulation by the likes of Facebook and Cambridge Analytica have begun to raise doubts over the security of the electronic voting machines (EVMs) on which ballots are cast.

The concern that, under BJP rule, the Election Commission was behaving like a government department, became more acute when the Delhi high court threw out an EC decision to disqualify twenty Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) MLAs of the Delhi Legislature on technical grounds, an action that could have benefited the BJP had byelections to their seats followed. The court termed the decision “bad in law”, “vitiated” and a failure to “comply with principles of natural justice”. How had an institution widely hailed as the impartial custodian of India’s democratic process allowed itself to be brought to such a sorry pass? The answer lay clearly with the ruling party at the Centre, which was seen by many as pressuring the institution to act according to its wishes.

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI), the nation’s central bank, was thoroughly discredited over the BJP government’s disastrous demonetisation of November 2016, when it was widely denounced for failing to perform its fiduciary duties. The RBI, which did not appear to have been fully consulted on the political decision, conspicuously failed to exercise its autonomy, to anticipate the problems of Mr Modi’s scheme, to prepare its implementation better, and to alleviate its impact.

During the shambolic demonetisation process, the goalposts kept shifting: the RBI issued multiple notifications on demonetisation some seventy-four in fifty days, each intended to tweak an earlier announcement. It seemed as if the Reserve Bank had been reduced to a puppet on a string for the Indian government. Many began to refer to this once-respected institution as the “Reverse Bank of India” for its frequent reversals of stance on such matters as the amounts of money permissible to withdraw, the last legal date for withdrawals, and even whether depositors would have their fingers marked with indelible ink so they could not withdraw their money too often.

Demonetisation caused serious and seemingly lasting damage to India’s most important financial institution. The United Forum of Reserve Bank Officers and Employees wrote to the government in January 2017, pointing to “operational mismanagement” which has “dented RBI’s autonomy and reputation beyond repair”. The inexplicable silence of its governor, Urjit Patel, reduced him to a lamb. But this “silence of the lamb” was cannibalising the RBI itself.

The Modi government has also not hesitated to politicise the armed forces, not just bypassing time-honoured principles of seniority in appointing the Army Chief, but by repeatedly using the Army in its political propaganda. The shameless exploitation of the 2016 “surgical strikes” along the Line of Control with Pakistan, and of a military raid in hot pursuit of rebels in Myanmar, as a party election tool something the Congress had never done despite having authorised several such strikes earlier marked a particularly disgraceful dilution of the principle that national security issues require both discretion and non-partisanship. As I’ve mentioned, the 2018 Karnataka state elections saw the Prime Minister, no less, falsely denouncing India’s first Prime Minister for allegedly having insulted two Army Chiefs from the state.

The principle that the Army should be kept out of politics, and that the military are above regional or religious loyalties, was disregarded in his flagrant exploitation of the Indian military for short-term purposes.

A controversy over leaked exam papers for an important national school-leavers’ examination cast doubt on another cherished national institution, the Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE), which conducts the test. The faith of millions of schoolchildren in the competitive examination system is vital for India’s social peace; in an environment where job seekers vastly exceed jobs available, unimpeachable exam results are fundamental to any perception of fairness. That the exam, which could make or break their futures, might have been leaked in advance to a favoured few casts a doubt on the entire culture of meritocracy that millions of young Indians aspire to.

Under the BJP, the federal investigative agencies (notably the Central Bureau of Investigation) are widely seen as instruments of the government; the CBI has even been described as a “caged parrot”. Its investigations and indictments, once seen as the gold standard of Indian crime-fighting, are now too often seen as purely politically motivated. As for the “temple of democracy”, the Indian Parliament, its work has been reduced to a farce as allies and supporters of the ruling party brought the Lok Sabha’s Budget Session to a standstill through disruptions orchestrated by the government. With the BJP-appointed Speaker claiming she could not count heads in the din, a motion of no-confidence moved by Opposition parties was initially not debated, citing “lack of order”.

It seemed as if the government was willing to destroy the temple rather than permit prayers against its misrule to be heard there. (The motion was eventually permitted to be introduced in the following session, but the damage was done.)