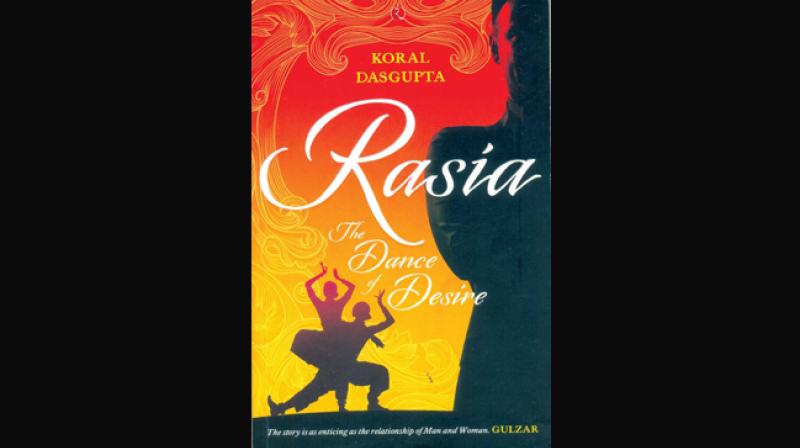

Book review: A delicate love story woven on Bharatanatyam's loom

The final resolution is somewhat philosophical, implying the glory of any great art form transcends bodily bindings.

Chennai: The narrative of writer Ms. Koral Dasgupta’s latest fiction, ‘Rasia: The Dance of Desire’, gracefully moves back and forth like the ‘108 Karanas’, the basic units of ‘Bharatanatyam’, and climaxes in an enlightening ‘Thillana’, the intentional movements of the artistes streaming from one socio-cultural space-time to another, from the Indian coasts to Manhattan.

At one level, it is about a dazzling yet lofty, meticulously planned over six months with a scholarly script drawing sustenance from Indian mythology, her composite culture and devotedly choreographed classical dance show, ‘Rasia’, which launches a famous Mumbai-based Bharatanatyam troupe in New York. But the ship gets larger, as it also simultaneously turns out to be a modern stage for unfurling the complexity of human minds, another defining moment aesthetically bringing to closure a proverbial love triangle.

The final resolution is somewhat philosophical, implying the glory of any great art form transcends bodily bindings.

Koral Dasgupta’s three characters who vie for this parallel romantic-cum-sacred space are the Bharatanatyam couple, Raj Shekhar Subramanian and Manasi, a seemingly accidental pair who begin their artistic journey with a chance meeting during a Durga Puja season in Kolkata. The third is an ambitious, “obsessed fan” of Raj Shekhar, enticing Vatsala Pandit, born to a half-Indian father and a British mother, a versatile ballet dancer, whose consuming desire is to scale the peak of Bharatanatyam alongside only Raj Shekhar on stage, not to steal his thunder but to affirm her equality with him, the primordial Shiva-Sakthi dilemma!

There is this great undying tradition of ‘Bharatnatyam’ that has come down over centuries from Bharat Muni’s ‘Natyashaastra’, as a technique of nuanced and embellished movements of the human body, fusing rhythm and music in its own way in conveying the appropriate ‘bhaava’ in communicating the soul’s ultimately seeking to become one with the divine. Yet, all these presuppose ‘Nritya’ or pure dance, as much as they assume a cosmology of the unity of Shiva and Sakthi.

As both a keeper of this tradition and yet innovating within it, Raj Shekhar is constantly on a pursuit of perfection and Manasi is his “first Bharatanatyam student”. Interestingly, in unraveling their personal predilections, particularly in the phase when Vatsala is determined to go any length to be part of his yet-to-be finest production to a larger Western audience that would give his institution a new profile, Koral Dasgupta so finely draws upon the triadic power play between Shiva, Durga and Kali as told in Hindu mythology, to resolve their dilemmas too.

It not only brings out that art forms like ‘Bharatnatyam’ and classical Indian music is much more than India’s ‘soft power’ abroad – ‘Yoga’ comparatively has been a more recent addition to that list - but also draws attention to the potential in creatively re-interpreting India’s cultural traditions without fixity to taboos.

In the novel, Manasi, reflecting on the roots of their craft, recalls Krishna’s monologue thus: “Goddess Kali is the consort of Lord Shiva, also referred to as Shakti, meaning energy. Lord Shiva is the salient aspect of the Transcendental reality and Mother Kali is the dynamic aspect of the Transcendental Reality. When Kali is performing her role, reality is moving. When Shiva is performing, reality is silent. Shiva never spoke a single word until Shakti came into his life as Parvati. Parvati assumed different roles to fulfill Shiva’s expectations from his wife. Shiva and Parvati are said to be the most ideal match.

As Annapoorna, the goddess of food, she fed him. As Kamakhya, the goddess of pleasure, she indulged with him in exploring physical ecstasy. As Gauri, demure and delicate, she allowed Shiva to dominate though she is beyond domination. As Durga, she protected. As Kali, undressed with hair unbound, undeterred to be herself, unafraid of being judged and mocked, she taught him to face the truth. Lalitha, the beautiful is also Bhairavi, the fearsome. Mangala, the auspicious, is also Chandika, the violent.

By opening herself to the totality for her Lord, Shakti allowed her true, complete self to be perceived by Shiva, thus assuming the role of a mirror which in turn helped Shiva to discover himself.” In their next manifestation, these dynamics of love-hate, beauty-ugliness, truth-untruth play out through the ‘Leela (sport)’ of Radha and Krishna, in a reversal of roles between Shiva and Shakti. ‘Maya’ is the power of transition, “divinely responsible for rejuvenating the rugged and the rusted.”

This passage from the novel gives an indication of the extent of symbolisms that Manasi has internalised in her journey with a Bharatanatyam artiste. She is no flamboyant girl like Vatsala, but she quietly applies her deeper understanding of the metaphysics and cosmology that has grounded ‘Bharatanatyam’ over centuries, far better than her husband, Raj Shekhar, who feels his carefully cultivated identity over the years was being rocked by the newcomer in his life.

It is not that Raj Shekhar, who having grown up in an orphanage and reaches the top through sheer dint of hard work is stupefied by his own ego. He has his reflective moments and plays the distance logic well in the novel. But circumstances are such that he lets Manasi script their new prestigious production, ‘Rasia’. It gives her the elbow room to rework that script and also enables a graceful resolution of the love tangle that threatens to engulf them.

Instead of the usual archetypical one partner in the proverbial love triangle having to give up or ‘sacrifice’, that the cosmology surrounding the ‘triple aspects’ of Goddess Shakti and Shiva could be creatively reinterpreted to resolve matters of the human heart, makes an absorbing read.