In the shadows of time: The life of Veer Savarkar

A co-accused in the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi, several charges have been levelled against Savarkar.

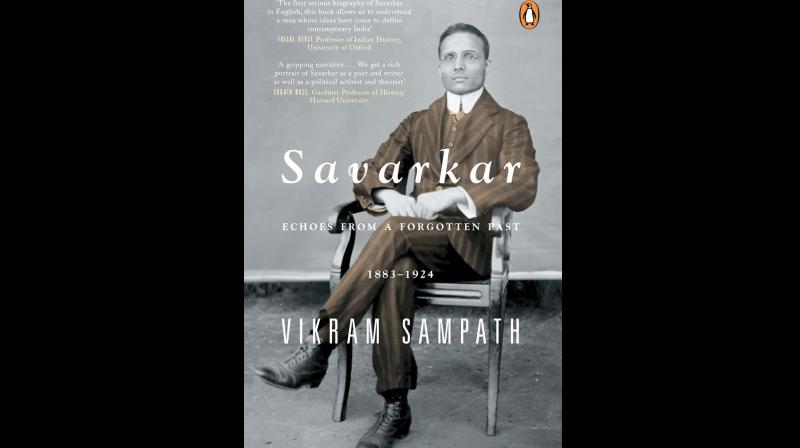

Recently, there has been a surge of interest in one freedom fighter’s life and ideology. This year alone, two biographies have been released so far of Vinayak Damodar ‘Veer’ Savarkar (1883-1966). Author Dr Vikram Sampath, whose book Veer Savarkar: Echoes From a Forgotten Past launches in the city, says that there is a growing hunger and interest among everyone, young included, to read about “those chapters of history that have been totally and intentionally wiped out”.

A co-accused in the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi, several charges have been levelled against Savarkar. These include, begging for release from the Cellular Jail in Andaman Island and inciting communal tension. Half a century after his death, his name still draws antipathy from critics, much admiration from sympathisers.

Sampath is a biographer of repute. His 2010 book, My Name is Gauhar Jaan, the story of a great artist who went on to die in penury, won him the Yuva Puraskar Award. In 2008, he wrote Splendours of Royal Mysore (a history of the Wodeyars) and in 2012, Voice of the Veena, the story of veena player S. Balachander.

Savarkar: Echoes from a forgotten past hit the stands in mid-August and praise has already begun to pour in for Sampath. “This book is not an apology for Savarkar, nor is it an attempt to correct any alleged historical wrongs that have been done to him,” says Sampath. “It is to bring to the readers the life and philosophy of a man whose thoughts have come to define India and her trajectory. It is also a different narrative of the freedom struggle, quite unlike the monochromatic one we have been fed. And given the minefield that his life was/is, I approached it with a completely open mind. I let the documents and the archival records speak for themselves. Many assumptions and preconceived ideas and notions were challenged in the process and my writing too and the narrative changed course in accordance.”

The first book covers the story of Savarkar’s life from birth to his conditional release in 1924. There are details about the atrocities done by the British on the prisoners of the Cellular Jail to references about freedom fighters like Shyamji Krishna Verma, Niranjan and Virendranath Chattopadhyay. If these names aren’t familiar, it merely underscores Vikram’s point: Some names have been obliterated in the dominant historical narrative.

Sampath’s fascination with Savarkar began when he first heard of him, back in 2003-04. “There was a controversy around dislodging his plaque at Cellular Jail, started by Mani Shankar Aiyar,” he recalls. It was only over the last three or four years that he managed to get down to doing serious research.

A Senior Fellowship from the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library (NMML) furthered the process. “I was quite amazed to know that a man who evokes such strong, polarising reactions even now, and whose philosophy and thoughts have shaped India in so many ways and continue to do, remains obscure. There was hardly any research on him, he has barely been written about.” He rummaged through archives across India and abroad, and through Savarkar’s own prolific writings in Marathi, which, he says, “have been seldom accessed by “mainstream historians”. He also interviewed old-time proponents and opponents, meeting Savarkar’s grand-nephew Ranjit Savarkar and travels to to Bhagpur, Nashik, Port Blair, Mumbai and London.

The Savarkar he unravelled was a bundle of contradictions. An atheist and a staunch rationalist who strongly opposed orthodox Hindu beliefs and dismissed cow worship as mere superstition, Savarkar was the most vocal political voice for the Hindu community through the entire course of the Indian freedom struggle. The social reformer in him strove to dismantle the scourges of untouchability and the caste hierarchies, and advocated a unification of Hindu society.

The spark of rebellion came to him young. A voracious reader, his intelligence and his talent for poetry were recognised even when he was in school. He went on to study law and became a firebrand revolutionary, credited with forming one of India’s first, organised secret societies in India. ‘Mitra Mela’ called for total freedom, even if that meant an armed struggle, just as the foundation was being laid for the Indian National Congress and the Moderates entered the spotlight.

A scholarship, for which he received a recommendation from Bal Gangadhar Tilak himself, took him to foreign shores. The five years he spent in London were tumultuous, as he built a vast network of revolutionaries across Europe, orchestrated bombings and political assassinations and also produced a huge corpus of intellectual output for the revolutionary movement.

And, rather unlike the stalwarts of the INC, he petrified the British. “They wanted to deport him, have him jailed in the most inhuman conditions in Cellular Jail in the Andamans - for 50 years,” says Sampath. Savarkar filed a petition, for which he receives the ire of mainstream political voices today... “Petitions were normal, legitimate recourse, available to most political prisoners,” Sampath explains.

As a barrister Savarkar knew the loopholes in the law and naturally, wanted to use every means available to free himself. He advised fellow revolutionaries to sign these petitions and to agree to conditions laid down by the British, but to continue with their own work.

Sampath debunks some misconceptions: Savarkar was never associated with RSS and his thesis on Hindutva does not have anything to do with the two-nation theory. “The blatant use of religion through the Khilafat movement, championed by Gandhi, the failure of this approach and the bloody communal riots that followed -- the Moplah riots in the Malabar, Kohat, Gulbarga, Delhi, Calcutta, Panipat, Calcutta, East Bengal, and Sindh to name a few, were viewed with horror by Savarkar and others. The pusillanimity with which the Hindu community was made to react to this movement and the ensuing riots inspired Savarkar to pen his treatise calling for a cultural identity of ‘Indianness’. It is in this context that Hindutva took birth to define anyone who considered this land as the land of their forefathers and/or a holy land to be a “Hindu”--not by the religious meaning of the term but a cultural and civilisational identity.”

In spite of the extensive task on hand, the book would have been released earlier but for the death of his mother last year. “This tragedy left me shattered and I grappled to put the pieces back together, summon internal strength and go on to write about someone as complex as Savarkar.”

Sampath himself has been labelled a ‘Sanghi’ and so on for his ideology. To his detractors, he counters: “Honestly, it makes absolutely no difference to me. I am not associated with any party, or with the RSS (have not even visited a shakha in my life to be a Sanghi) nor have I got/sought any favours for myself from the Government. I do hold a conservative political, scholarly, and academic position, which is no crime and a legitimate stand to take. But in today’s world of stark binaries and Bush-isms of either you are with us or against us, we love to label others and nuance has sadly died. Hence I have stopped explaining.”