Book Review | The rebranding of Hyderabad

It has become boringly commonplace to identify Hyderabad with biryani, Charminar and pearls. There was always more to my home city. My generation’s social life was not confined just to Hyderabad but spanned the “Twin Cities” of Hyderabad-Secunderabad. Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru called it “India’s Second Capital” and suggested the President of the republic spend a few weeks every year at the Rashtrapati Nilayam. However, till N.T. Rama Rao and P.V. Narasimha Rao placed the Telugus on the national stage, Hyderabad was treated as a distant cousin of the imperial urban centres of Bombay, Calcutta, Delhi and Madras.

Over the past decade Hyderabad has come to be seen through the prism of Cyberabad, encouraging a young Hyderabadi to recently go on social media and remind everyone that there is a city this side of Jubilee Hills and Gachi Bowli. Clearly, rapidly evolving Hyderabad has an identity crisis, caught between biryani and the back office. So we owe a debt of gratitude to Dinesh Sharma, a Hyderabadi himself, for reminding one and all that there's more to Hyderabad and, indeed, for a long time now.

Sharma’s focus is on the human capital foundations of an increasingly knowledge-based and globalised metropolis, and on the many individuals, institutions and enterprises that have enabled Hyderabad to emerge as one of the top three metropolitan centres of the country. Home to businesses of the 21st Century. One quibble though. Hyderabad was always ‘globalised’. As I elaborated in the Waheeduddin Khan Memorial Lecture 2006, at Hyderabad’s Centre for Economic and Social Studies, the city’s globalisation is rooted in its origins at Golconda. How else would this landlocked city of rocks and lakes become famous for pearls?

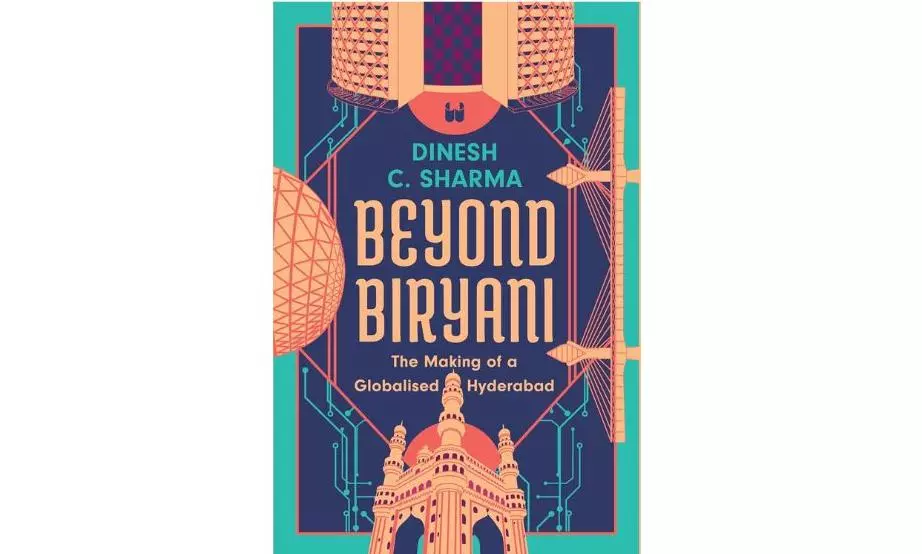

The main contribution of Sharma’s book is to catalogue the educational, scientific and technological development of Hyderabad from early 20th century. He shows how the location of industrial activity, research in the sciences, information technology, bio-technology and pharmaceutical manufacturing industries were all on account of the investment in human capital made first by the last two Nizams — Mahbub Ali and Osman Ali — and subsequently by a series of Congress Party and Telugu Desam governments. Sharma names several individuals across various fields of business, government, science, technology and education who have contributed to the city’s development. Perhaps chief minister Jalagam Vengal Rao deserved more attention, as did enterprises like BHEL and India’s best airport built by G.M. Rao.

Sharma’s narrative shows how the public policy lesson from Hyderabad’s development has been the fact that successive governments have built on their inheritance rather than waste it. Equally, the city’s enduring syncretic cosmopolitanism is its secret sauce. Sharma’s family migrated to the city as recently as the 1940s but his passion for it comes through the book. It used to be said that what makes a Hyderabadi is “Gandipet ka paani”. Sharma has certainly imbibed a lot of it.

Beyond Biryani: The Making of a Globalised Hyderabad

Dinesh C. Sharma

Westland

pp. 314; Rs 799