Earth heroes are greening India, protecting wildlife

With India having committed to create an additional carbon sink of 2.5 to three billion tonnes through increased forest cover by 2030, the involvement of every individual and institution in planting and protecting trees acquires new importance. Recognition also needs to be given to all those working in remote interiors to protect our flora and fauna, to save endangered wild life and green spaces from extinction. It is for this reason that the annual event to honour the country’s Earth heroes acquires added importance.

Committed to promoting sustainable livelihoods in ecologically vital landscapes of the country, for the seventh consecutive year, the Royal Bank of Scotland recognised and felicitated its Earth heroes recently. Of the 57 entries received, an eminent jury of veterans in nature and wildlife management selected nine of them; two of them joint awards. Jadav Payeng, who has single-handedly created a forest on 1,360 hectares of a sand bar on the Brahmaputra near Jorhat, epitomises the spirit required to combat climate change. Better known as the Forest Man, he has been an inspiration not just in India but globally.

Iprah Mekola from Arunachal Pradesh has spent 17 years in wildlife conservation. He is a member of the State Wildlife Advisory Board and an honorary wildlife warden of the lower Dibang Valley. As the head of the Mekola clan, Idu-Mishmi tribe, he has used his clout to create environment awareness among his people and started the movement for declaring the land of the Mekola clan a “community conserved area”. He has pioneered the formation of the Biodiversity Management Committee of Mekola and the People’s Biodiversity Register of Gimbo village. He has helped the Wildlife Trust of India (WTI) in the rescue and translocation of the hoolock gibbon and is working closing with the Bombay Natural History Society in the protection and regeneration of the endangered Bengal florican.

The Green Warrior says it’s a big bird, easily spotted and killed. There are just 300 of them in the world and a few in Arunachal Pradesh. To protect the florican, he released 500 mithun or local cows into their habitat and as per local customs, the area became his and no one can enter the area to shoot birds or wildlife. Now Iprah is working with village boys on bird conservation. He trains them to guide birdwatchers. On sighting a florican, a guide may be paid as much as Rs 500. There are just half a dozen floricans in the Dibang Valley, says Iprah. An unexpected bonus for the ecology of the region was the spurt in butterflies because of cow dung, says Iprah.

The story of the 19 hoolock gibbons he has rescued is equally fascinating. Gibbon meat is relished by some tribes and frequently when trees and forests are cut, the young gibbons fall down and are picked up and killed by dogs and hunters. With the support of the WTI, he has rescued gibbons and moved them to protected areas.

In 2013, Iprah even rescued two tiger cubs after their mother was killed. The tigress had a litter of four cubs. With the mother one cub was killed. The second cub disappeared in the jungles and Iprah rescued the remaining two and took them to Itanagar zoo. The male cub was named Mekola after him. Iprah’s latest worry is elephants and rebuilding of their forest corridors.

To stop hunting and killing of wild animals for their meat are two other major concerns. Self-imposed taboos are being subtly introduced. For five days after killing a wild animal, the man cannot ask his wife for sex, says Iprah. For economic empowerment, women in four villages adopted by Iprah, have been supported for broom grass cultivation. Bringing in money for the family, the women discourage men from going for hunting.

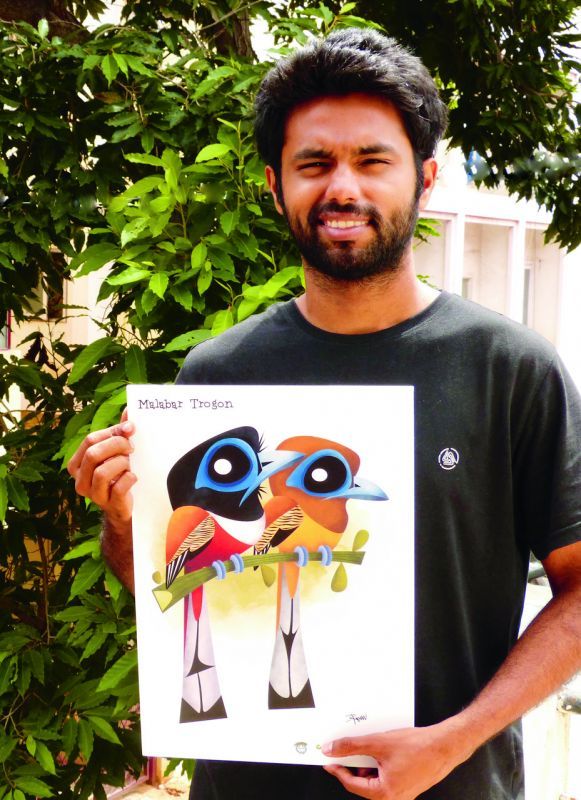

Another RBS “Inspire” Award winner, Rohan Chakravarty, 30, is a dentist-turned-wildlife cartoonist. He has pledged to use his award money to travel to Iprah’s Dibang Valley to document through drawings and cartoons wildlife of the area, and prepare a wildlife map of the region, which will be shared with the forest department and conservationists.

Rohan always drew and sketched but it was dentistry that he studied in college. On a visit to a tiger reserve near his hometown, Nagpur, he saw a magnificent tigress, which he went home and captured on paper. The tigress sighting changed his life and he plunged into wildlife cartooning. Sanctuary Asia began publishing his cartoons in 2012 and then Savus, also a wildlife magazine from Mumbai followed. Today he has weekly columns in English dailies, Round Glass, an environment magazine from Bengaluru and his comic strip, Green Humour, is syndicated by Universal Press Syndicate. His pet projects are illustrated maps. He particularly likes documenting tribes living around nature parks and the interdependence of parks and tribes. Currently, for WWF Hong Kong, he is documenting Hong Kong’s parks and wild species.

Though it has been a challenge to make the switch, it has been good for Rohan. A Web store, Red Bubble in the US, has a page for his artwork and it prints and ships his drawings and cartoons. For inspiration he goes on bird walks and revels in introducing lesser-known species to the layman. His most popular cartoon strip was of the Arctic tern. It migrates from one Pole to the other and has seen the polar bear as well as the penguin. His strip showed the tern mimicking the polar bear to the penguin and vice-versa.

Has there been a tangible impact of his cartoons? Yes, says Rohan. When he did a strip on the population of the marmoset — the smallest monkey species from the Amazon basin in South America — shrinking because of their demand as pets, a reader from Peru wrote back to assure him she would never keep a marmoset as a pet.

In addition to the individuals who received awards, the over 900 sq km Valmiki Tiger Reserve (VTR) in the West Champaran district of Bihar adjoining Nepal, received the Earth Guardian award. According to Dr Ranjit Sinh, chairman of the jury, VTR enjoys the top spot for governance of parks. It has the third best gharial terrain and the hog deer is staging a comeback.

According to R.B. Singh, chief conservator of forests (Bihar) and Amit Kumar, the park’s deputy director, though VTR came into existence in 1994, it was fragmented, had a porous border with UP and Nepal and till 2005 was a hub of criminal activities. When the forest department began planning for its development, it found a serious staff shortage. So 500 Taru tribals of the region were employed as contractual staff; 44 anti-poaching camps were established in the reserve and thereafter the focus shifted to improvement of the habitat.

Barely two to three per cent of the 900 sq km was grasslands, so vital for ungulates and wildlife. From 2008, weeds were removed and grasslands regenerated and the herbivore population improved. The tiger population bounced back and today there are 31 adult tigers and nine cubs, taking VTR to become the country’s top 15 tiger reserves. National Highway 28, passing through the buffer area and creating disturbance, was moved out of the reserve. Since the Gandak river often enters the reserve in the monsoons, six km of anti-erosion work was done to keep the river out of the protected area. Though the railway track and the trains passing through could not be removed, the speed of the trains was reduced from 60 kmph to 40 kmph to prevent wildlife being hit. The construction of road connecting India and Nepal through the reserve for movement of security forces was also averted. The construction of the metre-gauge railway link between Narkatiaganj and Bhiknatori near Nepal border was also stopped because it could affect a potential tiger breeding area.

This year over half a dozen rhinos from Chitwan National Park of Nepal strayed into VTR. Hopefully, the rhinos will return to VTR permanently making the park a tourist attraction like Corbett and Kanha.

The other heroes are Khenrab Phuntsog and Smanla Tsering who look after the Hemis National Park of Ladhak; Atul Deokar, East Pench Tiger Reserve, Maharashtra who with the support of the community is protecting the wild buffalo, the vulture and the giant Indian squirrel; Shekhar Kumar Niraj, additional principal chief conservator of forests (wildlife), Tamil Nadu, who is working with TRAFFIC has done tremendous work to arrest poaching; and Chandrakant Naik, deputy range officer, Karnataka forest department, who worked tirelessly for the recovery of the Kali Tiger Reserve.

The writer is a veteran journalist based in New Delhi