Dance without frontiers: K Viswanath Director who aims to revive classical arts

The entire experience of working in a K. Viswanth film was pure pleasure.

I awoke to an early morning call from an enthusiastic dance and film buff sharing the wonderful news that film director K. Viswanath had been awarded the prestigious Dadasaheb Phalke award for his outstanding contribution to the film industry.

As with all great artists, the highest award is given by the viewing public. K. Viswanath’s films have brought the highest standards of classical dance and music performance and themes, along with serious social issues, to appeal to every stratum of Telegu speakers and beyond in subtitled versions.

I was walking through the transit lounge at Frankfurt airport in July, 1988 when a young Telegu ayah ran over to tell me how much she loved the film in which she saw me. I assured her she was mistaken, but it turned out that even in a European airport, travel weary and with my young daughter, she immediately recognised me from the just-released Swarna Kamalam directed by K.Viswanath. Since then, any Telegu speaker I have ever met has seen this film multiple times, from the educated elite to rickshaw drivers who offer free transport.

I was living in a ground floor Bengali Market flat when two gentlemen arrived at my door and asked to come in and speak with me without introducing themselves. My instincts were correct, to offer them water and usher them in without knowing who they were. One was Rajan Misra of the famed Rajan-Sajan Misra vocal duo and the other, assistant producer K.G. Krishna Rao.

Filming was well underway and K. Viswanath had not yet settled on which dancer could inspire Meenakshi (Bhanupriya) the heroine of Swarna Kamalam to value her inherited dance tradition from her father, a Kuchipudi doyen, Seshendra Shastry. He considered Yamini Krishnamurthy and Sanjukta Panigrahi among others until he saw my interview on a Doordarshan breakfast show. This is what brought the two gentlemen to my door and their gentle inquiries if I had heard of K.Viswanath? “Sorry, no”, the film Shankarvaranam? ”Yes”.

The entire experience of working in a K. Viswanth film was pure pleasure. Whenever I have been asked about participation in more films I have always laughed that working with anyone else would be a step down so why do so when my life and career as a classical dancer is as a stage performer?

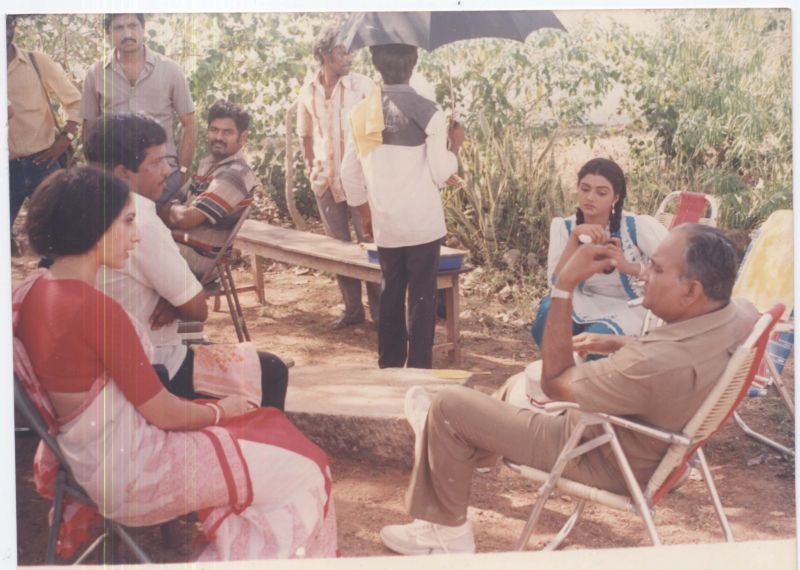

A still (right) from the making of Swarna Kamalam

A still (right) from the making of Swarna Kamalam

Performing as myself, Sharon Lowen, to help the heroine discover “the dance of the soul, not just of the limbs” did not automatically mean that I would be performing Odissi. Initially, the director wanted to arrange a month of training with Guru Vempati Chinna Satyam and perform Kuchipudi. He graciously honoured my concern that some details in my technique might be incorrect and also that I did not want to later be invited to perform Kuchipudi when I was not competent in the style.

Gracious is not a large enough word. He not only allowed me to perform Odissi, the first time it was ever featured in a Telegu film, but he also agreed to take the entire cast and crew to Bhubaneswar for recording as I wasn’t confident that the correct Odiya mardala (pakwaj) and other musical elements of Odissi would be well known by Chennai musicians.

Pt Bhubaneswar Misra, composer of most of today’s classical Odissi music repertoire, was extremely happy to share that the music recording for my Geeta Govinda ashtapadi in the film was the only time he had been able to fully orchestrate one of his compositions. He was such a gem of a human being as well as a brilliant composer and musician, not to mention mentor of Hari Prasad Chaurasia, that it touches me deeply to have made him happy.

Before the recording I arranged to connect with my guru in Canada to rechoreograph the ashtapadi to a fit the 7½ minute time frame. Theatre scholar Dhiren Dash arranged the Engineer’s auditorium in Bhubaneswar for the live performance filming.

After I carefully applied the traditional makeup used for Odissi, K. Vishwanath took one look and asked me to start over. He personally cut the silver side chains off my forehead tikka so my own persona was more visible and I have never worn them again seeing how much better this looked. His view was that exaggerated eye makeup was necessary for traditional male Kuchipudi dancers to look feminine but obscured the individual’s natural beauty in a woman.

I was amazed at the number of people involved in a film shoot, many times more than I was accustomed to in television studios. There was even a dedicated helper with a damp cloth so I could clean the bottom of my feet between shots! The crew was surprised that I didn’t have a dance director with me as I was used to having all of the dance set in advance and didn’t realise the advantage of having someone checking how the dance looked from different camera angles.

Besides the days of filming in Odisha, the Visakapatnam was closed for shooting our last scenes and we also had a wonderful week in Kashmir’s beautiful Yusmarg Gulmarg, Sonmarg and Pahalgam. Here the heroine’s dance expressed the inner meaning and joy of the dance in the paradise of glorious settings. The legendary film choreographer Gopi Krishna choreographed her culminating dance while I helped with the Manipuri and Odissi sequences and, at the request of K. Viswanath, added a few classical elements here and there to the rest. My daughter was the same age as Gopi Krishna’s and they played together, both passionate about drawing at the time.

K. Viswanath had a concern that audiences might not realise that I wasn’t Indian and asked if I could wear blue jeans in an introductory scene. Since I am not a jeans person, I suggested that my daughter might establish me as an American but he felt this wouldn’t match with the audience’s idea of a dancer.

With humour and subtlety, the film reveals a young woman who does not appreciate the value of the art passed on to her from her father until a handsome neighbour gently makes it possible for her to see its beauty. There is no romance until this is achieved, partly by taking her to see my performance. The hero, a handsome billboard painter, was played by Venkatesh early in his career, shortly after returning from getting an MBA from the Monterey Institute of International Studies California. It was a pleasure getting acquainted close to the start of his 30- year career that has now encompassed 72 films. I recall that at that time, he was working to perfect his Telugu dialogs, so soon after his time in the US.

I also enjoyed getting to know Bhanupriya who was an exceptional dancer as well as actress. Both Venkatesh and the heroine Bhanupriya received best actor and best actress Nandi awards for Swarna Kamalam.

With no desire to embark on a film career as I am committed to classical dance, I know that every film made by K. Viswanath is beloved by vast audiences and I knew that Swarna Kamalam was screened at the Indian panorama section of the 1988 International Film Festival of India, but writing this I just discovered that it was also shown at the Asia Pacific Film Festival and the Ann Arbor Film along with receiving three state Nandi Awards, three Cinema Express Awards, and two South Filmfare Awards, including a Nandi Award for Best Feature Film and a Filmfare Best Film Award (Telugu).

With his love and knowledge of Carnatic music and dance, K. Viswanath has highlighted themes that are credited with reviving public interest in classical performing arts. He deftly creates films that successfully and completely cross the art film/popular film divide. Besides the arts, he is passionate about strong social issue themes including caste, dowry and even disability and has made these films in Tamil and Hindi as well as Telugu.

Sankarabharanam showcased the guru-shishya relationship between an honourable classical singer and a prostitute’s daughter, raising issues of caste, class and religion as society looks askance at the nature of their relationship. Another from the cornucopia of his classics is Sagara Sangamam in which the amazing and professionally trained in various dance forms Kamal Haasan plays the part of a Kuchipudi dancer who wants to succeed without compromising on his values. What happens when he gives up dance and becomes an art critic is fascinating. This film was dubbed in Russian language and was screened at the Moscow International Film Festival post its Indian success.

From Devika Rani in 1970 and Prithviraj Kapoor in ’72 to Kasinathuni Viswanath now in 2017, the Dadasaheb Phalke award is truly India’s highest award for film. I look forward to this richly deserved honour for a great director resulting in a series of film festivals focusing on his wonderful range.

The writer is a respected exponent. She can be contacted at sharonlowen.

workshop@gmail.com.