Towards a better planet

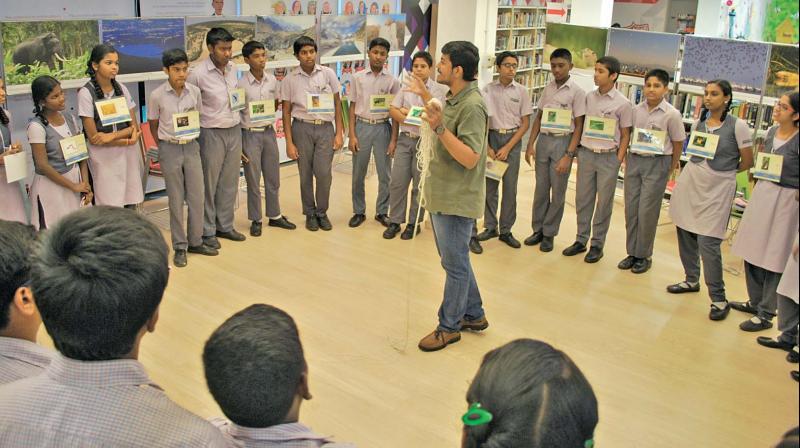

K Ramnath Chandrasekhar, award-winning wildlife photographer, conservation educator, and the co-founder of the Youth for Conservation, is holding a photo-exhibition titled ‘The Planet & You’ at the US Consulate General Library, Chennai. In addition, many critically acclaimed documentaries on wildlife conservation like The Race to save the Amur Falcon, are also being screened for school children. Chennai-based Ramnath speaks to DC about the importance of such initiative and other immediate environmental issues that has to be addressed in the country.

Tell us about your transition from a photographer/filmmaker to an educator. When did it happen?

It happened seven years back. Photography and filmmaking are the two mediums that I use to mobilise people to practice daily environmental efforts, and to empower students on the importance of nature and conservation. In 2008, when I came home after a long assignment in the rainforests of Western Ghats, I decided not only to photograph the wonders of the natural world, but to work with young students for a broader purpose. The trigger to this was watching and observing the works of wildlife filmmaker Shekar Dattatri. Since then I have been using his natural history and conservation documentaries, my photo stories and interactive activities to travel across Tamil Nadu to connect students with nature and conservation.

Many establishments including the government of USA, are attempting to downplay the effects of global warming. Being a conservation educator, how do you feel about it?

While there are many changes happening now to downplay the effects of global warming, we must realise that a lot of positive policies have been implemented too. For example, US, under the former president’s tenure implemented major changes like establishing the largest marine reserve in the world. I feel that one should look at the positives and find avenues to contribute towards nature and environment from our respective career backgrounds. When one reads stories of connect between Trinidad and Tobago Islands and Lake Chad, or the migration or Caribou in relation to mosquitoes, we will realise the gravity of climate change and the fragility of nature.

Also, can you elaborate on any first-hand experience of impacts of global warming during your ventures?

I experienced varied climatic conditions and changes in weather patterns when I was on an expedition to the Himalayas during winter. During this time, Zangskaris use the frozen Zangskar River to reach Leh in case of emergency and trade. They walk for around 90 kilometres just to reach Leh, and the same distance again to go back. Nowadays, winter has become short due to rise in temperatures. This makes the snow melt fast. It leads to severe shortage of water during winter. It is in such extreme places that one can explicitly see how the lives of people are shaped by nature, and how a little negative impact on the environment creates a domino effect.

You have earlier stated that the education system doesn’t teach students more about natural resources, which results in a scenario where people taking up Forest Administration Service are not aware of the need for conservation! What can be a possible change in terms of syllabus and courses to address the issue?

Change has to be brought in through a multi-pronged approach to address this issue. Enabling children to become problem solvers is very critical, if we are to build a society of ecologically conscious citizens. We need to connect children to the environment around them. We can facilitate them to map nature across different generations, and design hands-on initiatives through which young students can engage in social issues for a longer period of time during their formative years. Schools have a major role to play in this. To begin with, we need to progress from one-off outreach programs and enable children to observe, explore, communicate effective stories and resolve social problems, particularly towards environment in their own way.

Please share the experience of working in the making of The Race to Save the Amur Falcon.

I was honoured to work on this documentary as an assistant producer and editor to acclaimed wildlife filmmaker Shekar Dattatri. I learnt the art of telling compelling stories through moving images from concept to completion. It was an amazing experience to film the migration of Amur Falcons. And most importantly, the success story of the Amur Falcon campaign is a testimony that a small group of committed people can make a huge difference. It is the story of collective will, and it was an inspiring experience to have worked on the film with my mentor Shekar.

As a documentary filmmaker, do you find more space and audience for the genre in a country like India, where films are seen as a thing for entertainment?

I find that the spaces are fast increasing! Documentaries when combined with an educational design provides a tremendous canvas for teaching and learning.

What according to you is the immediate issue that has to be addressed in the state and the country?

The immediate issue that has to be addressed is to ensure that India’s strong wildlife laws aren’t diluted. And the last remaining protected areas that occupy only less than four per cent of India’s landmass has to be protected for our posterity. We must provide spaces for people to understand that nature can take care of us only if we take care of nature, and we must create avenues where people can contribute to nature and conservation from their own backgrounds in a sustained manner.