Breaking the mould

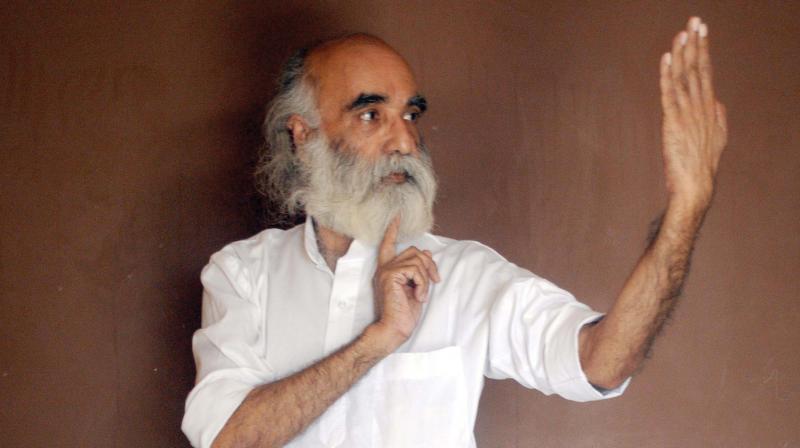

The first feature you notice about Guru Manu is his eyes — deep, calm, filled with mystery. Sporting a long silver beard, a spotless white kurta and saffron mundu, one would easily mistake him for a yogi. But when he starts talking, the Guru’s arms move gracefully, forming mudras and as if in a recital, he pulls you in, to his world of sadir. “Bharatanatyam is Sadir attam in Tamil-speaking regions. Widely considered a temple art form, it is actually based on Tantric philosophy. It’s an art form based on straight line movements involving all the eight directions,” he says as he gestures, demonstrating the hastas with arms forming a straight line.

A lone warrior who defies gender, racial and hegemonic stereotypes of classical dance, this man’s life is a textbook. Born into a middle class Muslim family in Kodungallur as Abdul Manaf, his penchant for dance was spotted by his brother-in-law Aboobacker, who used to take little Manu to Kathakali recitals and Kutcheris. Falling in love with dance, Manu used to jump across the compound wall of a school near his home to watch a dance teacher training the children.

Aboobacker enrolled him for Bharatanatyam classes, but the inevitable storm brewed and he soon became an outcaste. “It wasn’t from the Muslim community. Protests came from within my extended family and people around me,” he recalls.

His fort, back then, was Irinjalakuda, where he attended concerts and recitals, rubbed shoulders with maestros and got trained under masters like Kalamandalam Raghavan asan. “I learned Kathakali, Kathak and Mohiniyattam, but my heart lies in Bharatanatyam. I left Kerala to learn more and travelled across Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, where sadir followed the lasya-based Thanjavur system, and then to the North. I halted at many places, at times, spent years at one spot. My return to Kerala was after 30 years,” he says. At Madhya Pradesh, where he spent many years, he trained children in Bharatanatyam.

There, he got to associate with Bharatanatyam exponent Shankar Hombal, a direct disciple of Kalakshetra founder Rukmini Devi Arundale. Hombal considered him as his son and together, they run Kala Padma Institute in Bhopal. As years passed, he decided to take the learning further, outside books and scriptures, and went out to get first-hand experience from temple art works. His references were the temple sculptures in Tamil Nadu and south Karnataka, which immortalised dance moves on it. It was time for Guru Manu to make the move. In a transgressive attempt, he revolutionised Bharatanatyam, which is known for its fixed upper torso and spectacular footwork, by introducing bhangas and bhangis of sculptures to the dance form.

“What I have learned is that sadir has no original form. An art form that projects femininity, sadir is being traditionally practiced with no hip movements. But in every temple sculpture, the hip had bhangas and bhangis and I inculcated it in performance,” he says, demonstrating the posture of Krishna in traditional pose and his reformed version. He researched through paintings and sculptures in temples across the country, came across long-lost dance forms like Laavan. A wanderer, he took his artistic rebellion to places and trained children in his own style.

He is not a strict guru but is very particular that his disciples should give their whole heart to the art. “I do not train anyone who eyes competitions. Only a limited number of dancers take forward their passion. A lot of dancers are doing research and coming out with doctorates. Does anyone know what they have researched and found out?” In Kochi, where Guru Manu is on a halt between travels, he is training a small group of women — homemakers and artistes who are passionate about Bharatanatyam. He also conducts workshops for students. “My training technique involves developing inquisitiveness in my students so that they too get out of the fixed structures to explore more and experience the real sadir,” he concludes.