Attaining the little magic that our small lives yearn for

At times, poetry tries to achieve the simple things our hands can't accomplish. Say, the ability to sway the fingers of one hand asynchronous to the other. The symmetry hidden in the body pleads to be broken. It looks at the contradiction that the human condition is. It is a self unyielding to the simple desires that the body itself generates, and fails. Poetry obliges as a phantom limb, one driven by historical might and one that evolved through trials and failures. It replaces your fragile, failing hands to attain the little magic that our small lives yearn for; a little voice of our own, a little protest against the violations of the self, a little sunshine, a little love.

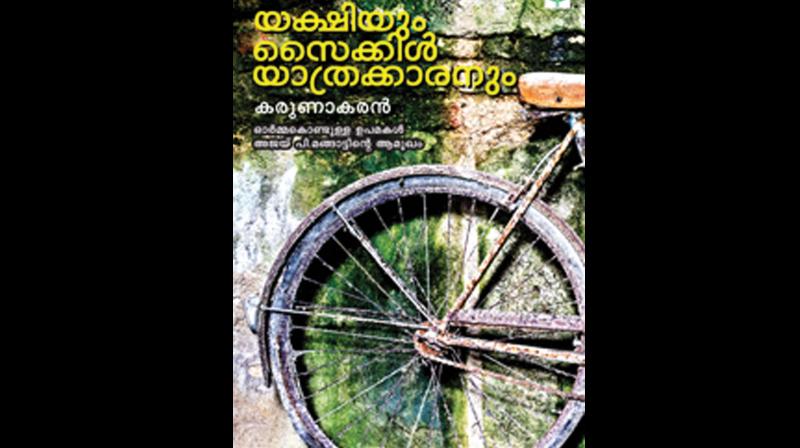

Karunnakaran’s poems become the poetic phantom limbs of our times. When the bigger, collective dreams that scaled up to a movement are withering away, the little yearnings truly represent the politics of the new, isolated and broken human. In his poetry collection, Yakshiyum Cycle Yathrakkaranum, the ‘Yakshi’ asynchronously rolls along with the miserable cyclist, two co-existing entities, and the Yakshi often becomes the alter poetic self accompanying the failing everyday Karunakaran, the common man up against all odds, riding lonely through a rough terrain. In contrast to what Anita Thampi observes about the poems in the blurb of the book, Karunakaran's poems (or the dialogue between Yakshi and the cyclist) do not come across as a breezy downhill joy ride.

The pace of the ride is slower than a stroll, the wind in your hair is a speed breaker, the route is a slippery uphill dirt track. The tiring cyclist is facing the daunting task of scaling a peak. With yakshi or the poetic self of Malayalam poetry itself as witness, the poems in this collection celebrate the slow ascent of the underdog to an unlikely victory. Scaling of the peak or the victory song never emerges, but the cyclist and the Yakshi are still singing a chorus of protest songs on their way up. The Yakshi accompanying the cyclist becomes a very interesting and apt choice in the narrative, as the voice speaking through these poems is often haunted (and still hurt) by what it leaves behind; a landscape of cultural and political unrest of the 70s in Kerala. The embers and ashes of it still remain at the fireplace of this poetic voice, but like a forgotten or fast fading memory of an acquaintance. As the poem 'Yakshi’ itself states, I know your wind and fragrance, but I have not quite seen you. Memory, thus is a corrective force, or so believes the voice in this collection.

The language and voice put forth, quarrels and often substitutes the feeble and drowning voice of the powerless, regular folk. The experience is akin to a near-death experience of a battling patient. Hence, I would like to call the proposition put forward by the collection as a near-poetic experience. Karunakaran views his poetry as a detached being, say the cat (Never thought I will be a poet) that crouches beneath the stairs. It travels with the uncle who set forth on a pilgrimage. The collection is also a dual between the opposites, throughout.

The jet plane, unlike the bird

Never loses its way,

Never lingers around

The memory of a past scent.

I have seen that land,

Longing for wings

sometimes at the speed of sin,

Like the sea in a chest.

At the old verandah

Of our vacated house,

Sometimes I see a

Tall, upright camel.

A non-resident (an outsider, rather) voice propels the tiny protests in these poems, often providing enough elbow room to raise a brow at the issues looming large over our being. His imagination of space is a redrawing of paths that no more leads to the same destination. Kuwait slides beneath Pattambi/Thrissur and vice versa, just as tectonic plates slide beneath one another. The experience of a place co-existing with another or that kind of layering dispels nostalgia, only to substitute it with a bigger global human state. In that sense, his poetry identifies with a larger global community.

Being a writer who approaches his own voice with curiosity and insecurity, Karunakaran lays bare in front of his own words, ready to fail. This steers his poetry clear of being authoritarian or definitive, and in turn readies itself for introspection and brutal criticism. The fear of a mute world without dissent echoes in every work. It stands out for its decision not to stand out, but to be another soloist in a chorus of grief, a candle of mourning in a sea of burning rage, another hoot from the sanctuary of imprisoned wings. In his own interesting ways, Karunakaran typifies that imagination is political. If the very basis of a democratic process (including voting, identity and so on) is the power to empower people to dream, there is something fundamentally wrong with the recent political trends we are subjected to. Karunakaran writes, to put up his hand and say, one more vote for the liberation of the oppressed. END

(Aditya Shankar is an Indian poet, flash fiction author and translator. He lives in Bengaluru)