What are we fighting for...?

The quest for understanding the self has been replaced with identity, the outer shell of awareness...

“Not to be absolutely certain is, I think, one of the essential things in rationality,” said Bertrand Russell, who is a much-quoted, scant-understood Colossus of philosophy among the politically-fired up youth of today, although whether or not this wave of adoration is certainly a matter of debate. Today, that which is Right (the opposite of ‘wrong’) is decided by the volume of protest that arises from the fevered masses, where history, equality, religion and art are laid bare for dissection by the blinkered understanding of the democracy. One must be reduced to labels, to the most immediate and apparent facets of our being and live within those rudimentary tenets. Irrespective of which side adheres to fact and which to fiction, for both are weaponised, the tragedy of this path will only be understood when it is actually upon us. Perhaps the greatest danger is the severing of one’s roots, for our concerns are second-hand, far-removed from anything we have known or felt or truly experienced. As the war rages on, the question that begs asking is: What are we fighting for?

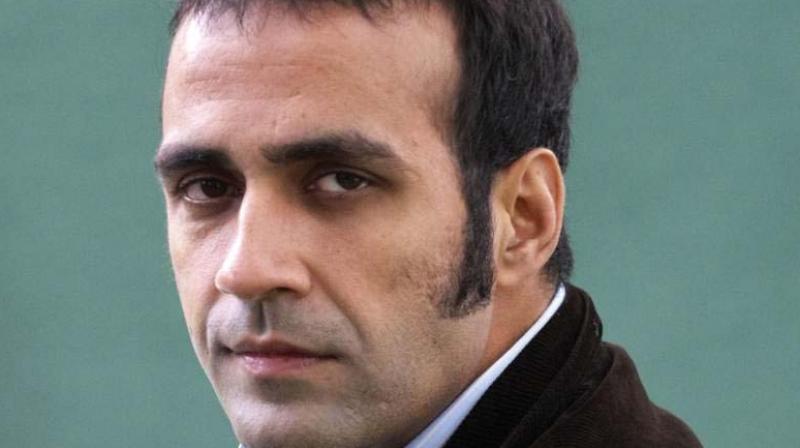

Aatish Taseer is no stranger to the quest for identity, as his writings will show, from his journey to Islam in Stranger to History and his exploration of Hinduism in The Temple Goers. To him, the quest has been deeply personal, sending him to Pakistan to trace his father’s legacy and to Benaras, where he explored the world in which his mother raised him. He dated British royalty and found love, in the end, with a “tall, white man from Tennessee,” as he beamingly describes his partner, Ryan Davis. Having been through the spectrum of the quest for belonging, perhaps there is more to being than will readily meet the eye.

His latest book, The Twice Born, talks of his time in Benaras and begins with a prescient word of caution from his friend, Mapu, "I fell in love with the city as a young man and it has always been my first love... But you have to hate it as well. You have to be able to look at that river and say, 'I hate you'. And when it gets too much, you must flee."

The quest for understanding the self has been replaced with identity, the outer shell of awareness...

What I’ve tried to do in my work is to use the personal to excavate the public. I have no interest in the world of identity politics; I don’t even believe I understand it. I believe in culture, and history, and the power of place over individuals. I also believe in what is concrete and specific, in the infinite variety of the individual. I work close to the ground; I’m much more interested in what someone ate for breakfast, and whether they spoke to their mother that morning before heading out to catch the bus, than their views on Islam, or Hinduism, or the rise of populism. Ideas and beliefs – and labels, as you say – should interest a writer only when, in Rebecca West’s words, he is able to demonstrate that they are “the symbols of relationships among real forces that make people late for breakfast, that take away their breakfast, that make them beat each other across the breakfast table…” When the world pulls the camera back so far that the individual disappears, the writer draws close.

In the fight for Utopia, everything must go...

In India, the Left has tried to disappear the history they do know, while the Right has tried to weaponize what they don’t know, but suspect. It’s an odious situation, because history is both a matter of pride and confidence, as well as a cold-blooded look at historical facts. In India, we have a real opportunity to make people richer for the complications of their history—to teach the palimpsest, as it were. This business of feeling oneself as under alien eyes – of looking, and being looked at – is rich with imaginative possibilities; it could be the basis of a new historiography in India. But one has to acknowledge historical pain before one can set it aside. Otherwise it will feed politics. What does Baldwin say? “Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

Will victory overshadow the losses?

My journey to Sanskrit began, as I said, with this very simple need to hear a voice from the past. The creative charge of that voice lay precisely in the fact that it was both recorded, and systematically denied me. That denial – we may even say, suppression – was not incidental; it was laden with historical meaning. And so, for someone as myself, to hear an utterance as simple as “Brihadasva uvaca” was suggestive. There’s a line in my book – “But loss, like absence, need not be inert; it can allow one to look with curiosity and feeling upon that which others, more culturally intact, have taken for granted” – that tries to capture this feeling. In India, something interesting will occur when we both renounce the hope of being whole again, while simultaneously acknowledging that ruins are full of possibility. There’s that terrific line in Dance of Shiva. “…we are called from the past and must make our home in the future. But to understand, to endorse with passionate conviction, and to love what we have left behind us is the only possible foundation for power.”

Lessons from history

You speak of Nalanda. Take something as simple as the Ram Temple in Ayodhya. Use that unhappy ground as inspiration. Don’t repeat the past. You want to build something? Build a dazzling institution of steel and glass – a foundation for historical and classical studies -- in which the brightest humanities students in the state of Uttar Pradesh, and beyond, can come to learn about the Indian past, with all its pain and complexity. Teach the problem of history, and the consolations of language, art and literature, and you would have accomplished much more than most.

On Islam...

I was just using what I had, exploring the implications of the personal. It’s hard for me to re-enter the passion of that time. Islam never meant much to me, but Pakistan, Urdu, my paternal family—they all meant a great deal. It was obsessional, but now that’s passed through the filter of writing, it’s gone cold. It feels like someone else’s quest. Often when I open a book of Urdu prose, I’m almost surprised that I can read it. There are these veins of interest, and when one comes to the end of a vein, one must move on.

The rise of the Activist, Provocateur

Let me put it like this: had Jack Dorsey the other day held up sign that said “Smash the English-speaking patriarchy,” by which he meant all those people who were the direct and indirect beneficiaries of their cultural nearness to the West, what would you thought of his ability to identify a true power elite in India? Or, let’s put it another way: say there was a full-fledged Leninist revolution in India, but instead of identifying its victims based on their class allegiances, they used language instead. Those with three generations or four generations of English speakers in their family were the first to be shot, and we proceeded in that fashion, generation by generation, identifying entrenched power purely in terms of language, how successful would the revolution be in its aims? It would be violent, to be sure; it would wreck the intellectual capacities of the country, as so many communist revolutions have; but would you say that it had zeroed in on those who truly constitute a fattened elite? How many of our “Left-wing” activists would survive such a revolution? Another question: how many times while travelling in India have you heard ordinary Indians identify themselves as Left or Right wing? They may say which party they’re supporting in an election, but that’s a different thing. The fact is that the “activism” you speak of has no reality on the ground in India. The battle lines themselves have no meaning in India. This is somebody else’s conversations, foisted on the Indian people, with the help of somebody else’s money. What Radomsky in Dostoevsky’s Idiot objects to about the Russian liberal is not his liberal views; it is that he has not been able to grow them on Russian soil and, in his failure, has developed a hatred of his place.

The dying romance of nationhood...

My parents were of a generation that was very romantic about their respective countries. I think that generation existed everywhere. I was reading The Yacoubian Building the other day, and one of the characters, a young girl called Busayna, talks of wanting to go to “a decent country, where there’s no dirt, no poverty, and no injustice.” She wants to raise her family in “a comfy little home,” and be in a place “where even the sweeper in the street gets respect,” and where she can be respectable.

I feel closer to that girl than to my parents. I want to be done with the demands of belonging. I want clean air and green spaces. I want museums and craft cocktails. I want the streets to be free of murderous fanatics. I want to be with who I want. I’m not interested in prophets and holy books. I don’t want to be hounded by a mob of jihadis, circumcised or uncircumcised, who feel sure that if only they look hard enough they will flush out a hidden tribalism in me. I don’t have a tribe, or a corner, or a group. I’m proud of my father’s personal courage, which often felt to me like a form of blindness; but, quite frankly, I’d just like to live in a place where people don’t die for saying what he did, or saying things at all.

On love, freedom and faith

Whatever challenges Ryan and I faced had to do with our families. We were both brought up by single mothers in places that were very different from those we came to. It took some time for such a varied moral landscape to level out. But it happened. Freedom, unlike faith, has demonstrable benefits. It elicits happiness, and happiness is not a culturally-specific emotion. As for New York, it has only ever been good to us. Here, as I told my mother, there’s nothing more bourgeois than being gay. In New York, if you’re not transgendered, you’re nobody.

(As told to Darshana Ramdev)

On Asia Bibi

I was thrilled for her – I’d like to see her out of that country – but naturally one cannot forget those young people who came out in their tens of thousands, upholding their right to kill her, affirming their bloodlust. The Islamic concept ofwajib al qatl is abroad among the people of Pakistan. It reminds me of the Roman jurisprudential idea of the homo sacer, the proscribed man, who may be killed by anybody, but may not be sacrificed in a religious ritual, and it chills the blood. What are we to think of the writ of a state that acquits Asia Bibi, and a

population that is in thrall to a different (and some will say, higher) law? I don’t know, I really don’t know…