Building stories: In the city of the future, small is beautiful

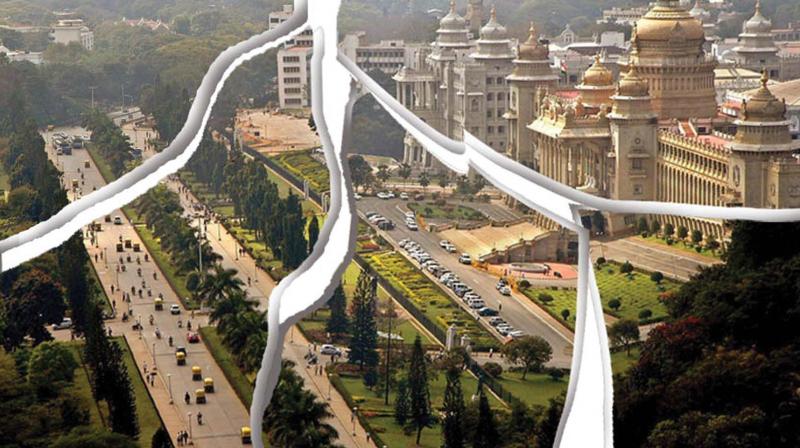

A lot of hand-wringing has gone into the question of whether BBMP should be divided.

Today's problems should be dealt with by administration. Tomorrow's challenges should be dealt with by anticipation and planning. The biggest weakness in the B.S. Patil Committee's recommendations is that its mandate, from the very beginning, did not allow it to propose ways to deal with the challenges ahead. Therefore, it was inevitably unlikely to propose the right set of choices for today either.

A lot of hand-wringing has gone into the question of whether BBMP should be divided. But virtually no one has bothered to offer a view on how much the city should keep growing. If, in a few years, the built-up area of the region extends from Hoskote to Ramnagara, should it still be governed as one city? Should every panchayat within the metropolitan region be abolished and be declared part of Bengaluru?

When we pose the questions this way, it is much clearer that there must be some logic by which we have to limit what we call the city. The only question is, exactly where is the dividing line between the city and the non-city? And how do we ensure that this line stays where we mark it?

Let's look at the facts on the ground. 850 people move into the BBMP area each day. Another 100 or so are moving into the rest of the BDA region beyond the boundaries of the city council's jurisdiction, and another 50 or so are moving into the metropolitan region of 8,000 square kilometres. That's 1,000 people a day. In three years, this part of our state adds one more Mysuru. In a decade, we'll add three times the population of the second largest city.

There is no chance of reversing this in the near future. Large parts of India have no economic vitality, and as a result, there is wholesale migration to the metros from virtually everywhere else. The top dozen urban areas in the country now hold 150 million people in less than 2% of the land. In 20 years, that number will cross 200 million. Bengaluru is near the top of the wishlist of that massive migration.

Within Karnataka too, there is steadfast refusal in government to grow any other city. It doesn't seem to matter who is in power, the gap between the capital city and the rest of the state continues to grow. Economically, demographically, and inevitably socially, we are on a bullet train without breaks or a steering wheel.

Now let's come back to the committees – and I use the plural because this is not the first time we're seeing recommendations for how to manage the growth of Bengaluru. But they were – and are – all constrained by the same cold facts. If we accept that there are limits to the growth of the city, then we must be prepared to say where the city ends. And if urban sprawl continues beyond this boundary, then we must decide how we will govern those places too.

And amidst all this, is the law. The Constitution, dating back to 1992, already tells us how a metropolitan region should be governed. Multiple municipalities should be brought together in the form of a metropolitan regional planning body. Each municipality should align its plan to that of the region. Each ward within each municipality should have a citizens' committee to select its preferred paths of development. This is the law.

But governments have gone on for 25 years as though this legal contour doesn't exist. Now the courts, nudged on by some citizens, are asking why the government is not following the law. Typically, the state government has responded with tactical answers, but we've reached the end of the line on that. The tactful stuff is self-evidently failing, and even a tolerant court is able to see that. Now the only things that remain are for the government to accept the reality we face, and for citizens to remember that the status quo is not a solution.

Of course there are other things that matter. The city has a great brand. Its history and heritage include special people and their contributions. Its economy is the engine of the state. These things should not be ignored. But surely it is possible to dramatically improve governance of the city and the region without losing any of this. We must trust ourselves enough to do that.

Smaller cities will be good. They will bring governance closer to the people. An integrated planning body can hold them together in a single well-woven economic and social fabric. And people's participation in everyday governance can be a pillar of support for these goals. What's left is to do these things.