Unsung Heroes and Unheard Stories

History cannot be obliterated by non-acknowledging the contributions of pioneers. Many who narrate India’s decentralisation story begin with the speech of former prime minister Rajiv Gandhi that only 15 paise out of every rupee spent reach the real beneficiary. A centralised and top-down system was considered primarily responsible for this pilferage of resources and the possible solution envisaged was empowerment of the local governments and through them the citizen. This vision was followed by the constitutional amendments to recognise local governments.

Indian democracy and its experiments with democratic decentralisation have a rich history. The debate was whether ‘democratic’ and ‘decentralisation’ can be contradictory to each other. This was behind the fear of elite capture of local institutions and depriving the poor of their voices. The Gandhian concept of Grama Swaraj was not accorded the pride of place in the Constitution mainly because of this.

The Gandhian views were revived by Jayaprakash Narayan, who got devoted to Sarvodaya travelling far from Marxism and state socialism. His opinion reflected in the essay ‘A plea for reconstruction of Indian polity’ was received with scepticism by some political scientists and other intellectuals, who felt that it would lead to dismantling of political democracy based on individualism. The idea of decentralisation also received support from communists in Kerala, especially E.M.S. Namboodiripad.

After the stagnation in decentralisation efforts in the 1960s and 1970s, efforts were revived by the Janata Party government by appointing the Asoka Mehta committee, which submitted its report in 1978. It recommended according constitutional status to local governments. Though the report did not find immediate acceptability, there were substantial efforts in Karnataka and West Bengal.

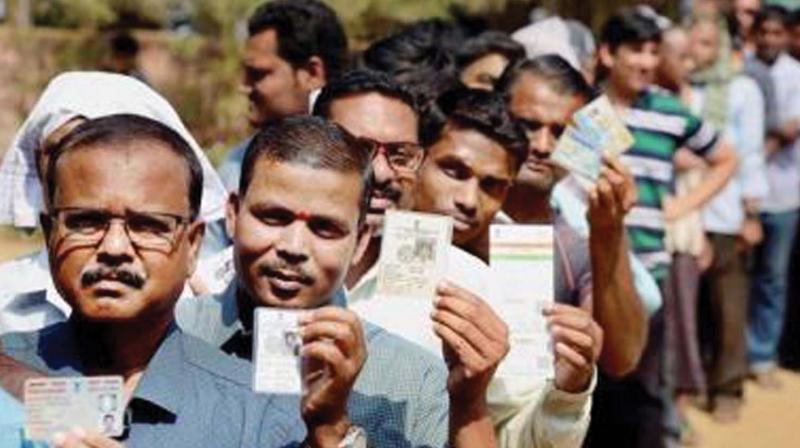

Though more than 25 years have passed after the 73rd and 74th constitutional amendments, real decentralisation is still a long way off. The local government elections are also not being held every five years. When we are in the campaign time of Parliament elections, one needs to be reminded of this. More than this, the local governments have become agencies of implementing programmes designed at the central and state levels. This is mere delegation or de-concentration and not decentralisation.

It is here that the unheard stories of unsung heroes assume importance. If delegation is what is aimed at, even colonial governments did it in stages. A vibrant decision-making local governance with no elite capture is still a dream. Gandhians and the leftists have their own reasons for being protagonists of decentralisation. The history of decentralisation did not begin in the 1980s. We cannot ignore thinkers and policy makers at various levels and their experiments. Gandhian idea was considered utopian by many because of their own genuine apprehensions when Constitution was being written. But those who attempted decentralisation through ideas and practices like Jayaprakash Narayan, Abdul Naseer Saheb and many others are not remembered at all in the decentralisation narratives. E.M.S. is an exception.

Relieving the centralised authority of some functions by delegation is not decentralisation. It is to appreciate this that we need to go back to the unsung heroes to read their unheard or not so much heard views like those in the ‘Plea for reconstruction of Indian polity,’ at least for an informed difference of opinion. Apart from economic reasoning, there is a sound basis to make decentralisation democratic instead of power delegation. It will be a very effective answer to hierarchy appearing in many forms, though each one is undemocratic in content.