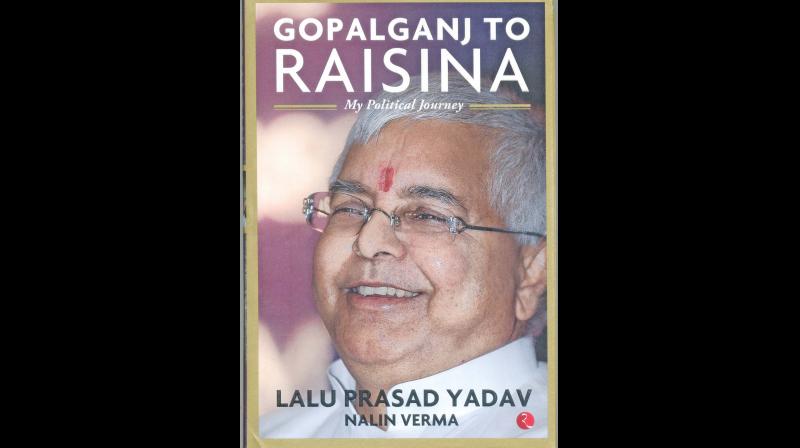

Lalu Prasad Yadav’s memoir - a glowing lantern to post-Mandal India

CHENNAI: He is a charismatic rustic who can use the ‘Bhojpuri’ dialect with stunning, stinging effect. For him the art of mimicry and acting came naturally, to imprint his wit and satire a distinctness of its own from the Indo-Gangetic plain. He could make people laugh and could laugh at himself too. He also admits to a phase of being indifferent and arrogant even to his own party men, followed by a course correction. And for the national press, he was always ‘colour copy’, ‘most entertaining politician’ from the ‘Janata Parivar’ who later founded Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) when the Janata Dal (JD) split in July 1997.

Born (My school certificate has it as 11 June 1948 as he candidly puts it) and brought up in a remote village of Phulwaria in what is now Gopalgang district of Bihar, one of Lalu Prasad Yadav’s biggest regrets to this day, since he passed his matriculation examination in 1965, is “I don’t have a photograph of my father.”

His has been a spectacular, roller-coaster political career: Influenced by Ram Manohar Lohia’s socialism from his student days and a product of the ‘JP

Movement’ in Bihar, from being one of the youngest MPs’ from Bihar, the state’s best known Chief Minister in the 1990s’, to his crowning moments as the Union Railway Minister in the Congress-led UPA-I government. Lalu was hailed for turning around the Railways from near-bankruptcy to a billion dollars surplus that even made the Harvard Business School to sit up and take notice of the Lalu model of leveraging. Now it is a phase of ‘in and out of jails’ amid hospitaliations. Yet, he remains a resolute fighter of politics of religious/communal polarisation.

But Lalu’s story is not just this nutshell of the extraordinary rise of an ordinary man from a humble cattle-owning-rearing community. “I belong to the Yaduvanshi clan of Lord Krishna,” he says. It is not political closure for him as yet, even if his son Tejashwi Yadav has taken over the party reins, as the opposition leader in Bihar after Lalu’s friend-turned-foe Nitish Kumar’s crossover to the BJP.

There is a deeper text and meaning to this wonderfully lucid autobiography by Lalu Prasad, co-authored with veteran journalist Nalin Verma, titled ‘Gopalganj to Raisina- My Political Journey-’. A narrative shorn of exaggerations, either in his top bullish or miserably bearish moments in politics, even as its’ high points retain the fluidity of a mighty river that has shaped a culture over centuries in the plains.

The wider significance of Lalu’s memoir cannot be missed in an important election year. In post-Independent India, socio-political movements to empower the long-oppressed BCs/OBCs/SCs and minorities, have after their first exuberance, hit a plateau. That is when the sword of anti-corruption dangles in an all-knowing moralistic sheen.

This pattern can be noticed since the early 1970s’, often camouflaging an upper caste backlash when regional parties that seek to give new political space to the OBCs’, Dalits and minorities were on the rise. In Tamil Nadu for instance, it happened to the DMK under late M Karunanidhi’s leadership, and more recently catching up with the AIADMK post-Jayalalithaa. Sans strong regional leaders, the ‘cusp of change’ is euphemism for re-defining caste equations in the polity.

Lalu Prasad Yadav’s rise and fall in national politics shows that he fell to the same axe of the “most vicious campaign on the issue of corruption” in recent years. The impact could be far more severe in states like U.P. and Bihar where traditionally the upper castes have always had a larger say in politics, economics and society.

While the first major anti-establishment wave came with the ‘JP Movement’ in the early 1970s-, by when Lalu had already become a well known student leader and had won JP’s confidence , suffered the incarceration of the Emergency and so on, the Janata Party experiment, after their spectacular 1977 victory, turned out to be short-lived. “JP wanted to make Jagjivan Ram, a veteran freedom fighter and prominent Dalit leader the Prime Minister”, writes Lalu. But even at the very beginning JP was heartbroken when “some senior political leaders conspired to impose Morarji Desai as the Prime Minister against the Loknayak’s wish.” Lalu by then had also become very close to Chandra Shekhar, “the Young Turk smiled and laughed whenever I spoke to him.” He later also became close to Charan Singh, all helping to push Lohia’s policies.

The impact was felt more in Bihar when Lalu was elected MLA from Sonepur. Despite churnings in the ‘Janata Parivar’ post-1980s’, he played a key role in trying to re-unify the various Lok Dal factions in the State. “I was not a fly-by-night MLA; I used to live among the suffering people during the floods. I used to cross the Ganga from Patna by boat to Sonepur on its northern bank,.. go to the rich farmers’ homes in Saran district and request help in the form of foodgrains to feed the flood-affected sheltering along railway tracks and embankments……..After distributing the relief materials, I lived with the people in their makeshift shelters at the time of floods, entertained them, made them smile and laugh with my rustic talk, even in the hour or crisis.” It was such actions of reaching out to the people, which sowed the seeds of Lalu becoming a ‘mass leader’ in subsequent years. These gave Lalu the stamp of sincerity and credibility to take forward the great Karpoori Thakur’s social justice legacy as Bihar CM later.

Lalu was slowly but surely empowering the poor BCs’, Dalits and minorities in Bihar whom he says hardly had any access to government machinery since Independence. He abolished the tax on tapping and selling toddy, raised minimum wage for agriculture workers and opened ‘150 charwaha schools’ across the State so that “the cowherds could study while their cattle graed”.

But at the national level the political instability was taking new contours. Post-1989, when the V.P. Singh-led National Front Government was on the verge of collapse, thanks to the powerful Haryana farmers and Jaat leader Devi Lal, Lalu writes that it was he who convinced V P Singh to implement the ‘Mandal Commission’ report reserving 27 per cent of Central government jobs to OBCs’.

That one-stroke measure though turned out to be a big political game-changer. It led to violent upper castes’ backlash in parts of North India and the instant

galvanisation of the ‘Ram Temple Movement’ when BJP under L K Advani’s leadership decided to take on the VHP’s agenda; Advani’s ‘Rath Yatra’ and Lalu, ignoring central leadership’s pussy-footing on this issue, stopping it in Bihar and ordering his arrest, opened a new confrontationist phase in Indian politics.

‘Mandir’ was an explosive response to ‘Mandal’, the upper castes’ bid to consolidate on religious lines while weakening the OBCs’/Dalits/minorities-axis.

These political battles are being fought even today. Though Lalu Prasad says the “political rivalry between the ABVP (and the larger Sangh Parivar) and him” goes back to his contesting the Patna University Students Union elections in 1973-74, rubbing Ravi Shankar Prasad on the wrong side, it was his “commitment to the empowerment” of the lowly sections that earned him the upper castes’ wrath, felt even today. “They presented me as a hater of the upper castes”, writes Lalu as this dialectic, he fears, even plays out in the corruption cases against him.

This is the deeper instructive grammar of Lalu’s memoir. The heartwarming journey is also laced with insightful, juicy anecdotes, like his role in H D Deve Gowda and I K Gujral becoming Prime Ministers, then Congress President Sitaram Kesari suggesting that Lalu make his wife Rabri Devi as Bihar CM when CBI booked the first case and so on.

Equally, Lalu’s passion for an egalitarian, secular, cosmopolitan India wafts through the elegant prose of Nalin Varma. The book is a must-read for all students of contemporary Indian politics.