Gandhi Smriti: Death by digitisation

New Delhi: On Thursday, 14 days before the nation observes the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi on January 30 as Martyr’s Day, several officials, people and journalists turned up at Gandhi Smriti in search of the panels displaying Henri Cartier-Bresson’s iconic photographs.

Tushar Gandhi, Mahatma Gandhi’s great-grandson, who visited the Gandhi Smriti on Wednesday morning, had tweeted on Thursday morning, ”Shocked. The evocative photo-gallery of Henri Cartier-Bresson displaying the post-murder photographs from the Gandhi Smriti have been removed from display on the orders of the Pradhan Sevak… He Ram!”

The large, sepia panels that used to adorn the cream walls of the main gallery in the bungalow that what was once Birla House, and in whose garden Gandhiji was shot dead by Nathuram Godse, have, indeed, been removed and moved to the godown. In place of the evocative snapshots of history now hang LG flat-screen TV sets displaying a much smaller, carefully selected set of photographs, each arriving at an interval of 30 seconds.

Gandhi Smriti’s director, Dipanker Shri Gyan, arrived along with Kumar Prashant, president of Gandhi Peace Foundation. Mr Prashant too had learnt of the panels being taken off from Twitter and had come to see for himself.

Mr Gyan said that the panels have been dropped because these days children, including his son, have short attention spans and want digital access.

”Gandhiji ko nayi pidhi ke layek nahin banana hai, nayi pidhi ko Gandhiji ke layak banana hai,” Mr Prashant said, responding to his explanation.

On being requested, Mr Gyan obliged and asked that the panels be brought out.

At least six large, thematic panels — a collage of photographs and text — have been removed from Gandhi Smriti’s main gallery.

One carried photographs by Cartier-Bresson on Gandhi’s final hours before his assassination, his mortal remains lying in state at Birla House and his funeral.

There was another panel with a photograph of Gandhi and Rabindranath Tagore, and one of Gandhi with Subhash Chandra Bose.

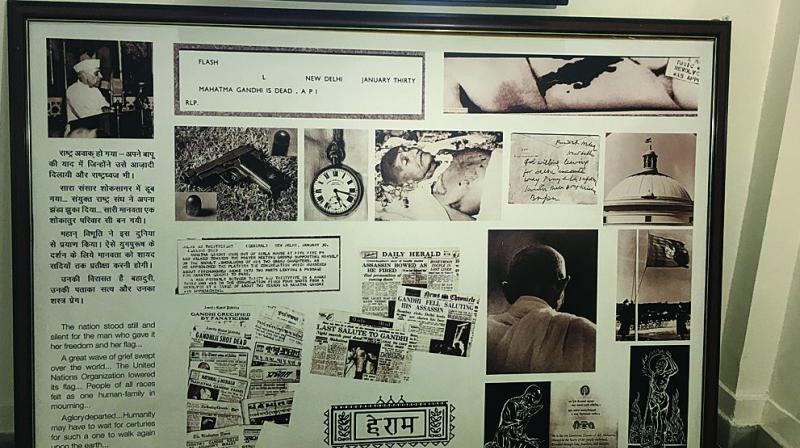

One panel was on Gandhi’s assassination and had several photographs, including of the pistol that was used to kill Gandhi, his pocket watch, and newspaper headlines, announcing his murder: “Assassin bowed as he fired” (Daily Herald); “Gandhi fell saluting his assassin” (News Chronicle); “Gandhi Crucified by Fanaticism” (Amrita Bazar Patrika).

Along with this was a news despatch that day, in the original font: “Mahatma Gandhi came out of Birla House at 5.05 PM and walked towards the prayer meeting ground supporting himself on the shoulders of his two grand-daughters. As he approached the platform, the congregation which numbered about 500, broke into two parts, leaving a passage for Mahatma Gandhi to pass.

A man, probably between 30 and 35, in a khaki tunic who was in the congregation, fired four shots from a revolver at a range of about two yards as Mahatma Gandhi was approaching.”

None of this has found room in the pen drives stuck into the flat screens of the displays.

The Gandhi Smriti, which officials says was undergoing renovation, opened to the public with this dramatic change on Wednesday without any official communication.

While some officials said that Gandhi Smriti was closed for two weeks, the director said it was closed for a month and as there was immense pressure to reopen, the work is incomplete and more information and photographs will be uploaded.

A few feet from the main gallery is the spot where Gandhi was shot. And Cartier-Bresson’s photographs of that day and the Gandhiji’s funeral that followed have been described as “not the portrait of any man, but the portrait of a nation in the deepest moment of its sorrow”. They include photographs of Nehru in anguish, his stunned face reflecting a nation’s shock and sorrow.

The Cartier-Bresson panel and another one had at least five photographs of Nehru, but now just one remains.

The gallery’s main panel had just one photograph by Cartier-Bresson — an image of Jawaharlal Nehru on the gate of Birla House announcing Gandhi’s death on the night of January 30, 1948 — along with the text of his address to the nation on All India Radio that night.

Now that photograph flashes on a TV screen for 30 seconds with his speech abridged to three sentences: “Friends and Comrades, the light has gone out of our lives and there is darkness everywhere… The light has gone out, I said, and yet I was wrong. For the light that shone in this country was no ordinary light. The light that has illumined this country for these many years will illumine this country for many more years.”

Lost in the ellipses is this line from Nehru’s extempore speech: “I do not know what to tell you and how to say it, our beloved leader, Bapu as we called him, the Father of the Nation, is no more.”

The Gandhi Smriti, though an autonomous body, comes under the culture ministry and depends on its grants. The ministry had issued an order to digitise the gallery, therefore the change.

The order, however, did not specify that the panels be replaced. The screens and the quaint panels could have stayed, side by side.

“One of the TV screens has the song Vaishnav Jan To… sung by people from 124 countries… It is interactive. Click on a country and the song comes on,” Mr Gyan says and demonstrates. He picks China.

While the bureaucratic order and the explanation seem like the usual, benign, unthinking action of a sarkari organisation, that doesn’t seem to be the case if you consider what’s been excluded. And coming close on the heels of the government’s decision to drop Abide With Me from Beating The Retreat ceremony, it smacks of another assassination plan.

“There is no agenda,” Mr Gyan says, and talks of people’s eight-second attention span. “No one wants to read,” he adds.

“That’s not true,” Mr Prakash says. “People read. They want to read. We need to see what we are putting out for them to read.”

“Main bahut baar aata hoon yahan par, aur ek feeling hoti hai... I think that we should try and humanise this feeling, not digitalise it. There are many other spaces for it (digitisation). If we keep that in mind, then this decision becomes easy to review,” Mr Prakash said.

Gandhi Smriti is an autonomous body, Mr Gyan says again, twice. But when pressed about who specifically took the decision, he says the minister, without specifying which one — just to digitise, or to also remove the panels.

Till 2014, a Gandhian used to be the vice-chairperson of Gandhi Smriti. This changed when the BJP government came to power. Since then the culture minister is the vice-chairperson, and the director reports to him.

The last Gandhian to hold the post of vice-chair was Tara Gandhi, Gandhiji grand-daughter. The current vice-chair is culture minister Prahlad Singh Patel.

The Prime Minister is Gandhi Smriti’s ex officio chairperson.

“All the material is there and we can put it. We can put both, there is no issue. All I need is a carpenter and two days,” Mr Gyan says repeatedly, and then adds, “We can’t put both.”

Next to the main, now digitised gallery is a carpeted room with what I can only describe as digital tables that react to touch. They will offer some interactive experience when operational. The walls of this long room are white and barren. There is space for at least 10 flat screens, if not more.

The gallery across the main gallery is devoted to Gandhiji’s 18-Point Constructive Programme. Its first item is “Communal Unity”. All these panels are intact. For now.