RTE in pre-schools: End of anganwadis?

It was a move intended to give poor students a shot at getting an education in private schools, which they could otherwise not afford.

The proposed extension of the Right to Education (RTE) to private pre-schools is a revolutionary idea no doubt and offers poor kids a chance to avail better educational facilities in these schools. But will it sound the death knell for the numerous anganwadis and state-run pre-schools which are already facing a dearth of students? There are some experts who contend that instead of reimbursing money to private schools for providing RTE seats to the poor, the government could spend this money to improve facilities in govt schools themselves and make them attractive enough.

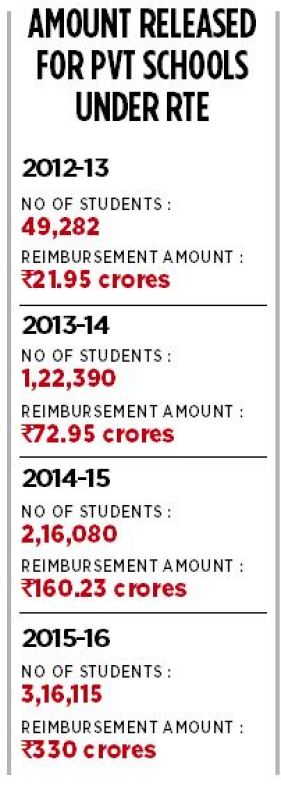

It was a move intended to give poor students a shot at getting an education in private schools, which they could otherwise not afford. But the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act, 2009, that provides for reservation of 25 per cent of seats in private schools for underprivileged children with the government paying the fee on their behalf, has kicked up a controversy of late as a number of state schools are now facing closure due to a dearth of students.

Critics are laying the blame squarely at the door of the Central legislation, and the state government for toeing its line when it had no compulsion to do so.

Read: RTE in pre-schools: Tug of war between activists, politicians

Soon there could be more reason for them to complain as the ambit of the Act could widen shortly. While currently the RTE quota applies to the pre-primary level in private schools, the Central Advisory Board of Education (CABE) is meeting on October 25 in New Delhi to discuss extending it to pre-schools and secondary education as well.

Read: GUEST COLUMN: ‘Demand for quota cancellation ridiculous’

D Shashikumar, general secretary Karnataka Associated Managements of English Medium Schools (KAMS) said, “Presently, the RTE quota is implemented at the pre-primary level in LKG and UKG. Children who are three years and 10 months old are admitted to LKG. But should RTE apply to pre-school as well, then day care centers and montessoris too will have to reserve seats for underprivileged children, who could be just two- years-old.” The possibility is alarming for those who believe the government is neglecting its own schools in the name of RTE. While they seem to be emptying out due to the RTE quota in private schools, they fear the anganwadis too could take a beating if their students have the option of entering montessoris and private day care centres.

Some officials of the department of women and child welfare too are anxious that the extension of the RTE quota to pre-schools could sound the death-knell for anganawadis in urban and semi-urban areas, where they are already facing an acute shortage of students.

“If RTE is implemented in pre -schools most poor students will opt for them,” said one officer. Strongly opposing the idea, she notes that angawadis play a key role in the lives of both mother and child. “The anganawadis staff work for a social cause, but private players have no such ideals,” she argues.

But then there are those who feel poor children need be given an opportunity to go to a montessori or a private day care centre. Say some officials of the Department of Public Instruction, “Extending RTE to pre-school will ensure a level playing field for all children in early learning.”

However, activist, Harish B Bhat, believes extending the RTE quota to pre-schools may not work out in the long run. His argument? Children from poor families, who go to anganawadis till they are five years and 10 months old , have good nutritious food to look forward to at these centres, but in pre- schools they will have no such incentive and this could make them unattractive to many.

His views may offer comfort to those wishing the RTE quota away in pre-schools. But in the final analysis its about what's best for the children and clearly the decision should be theirs.