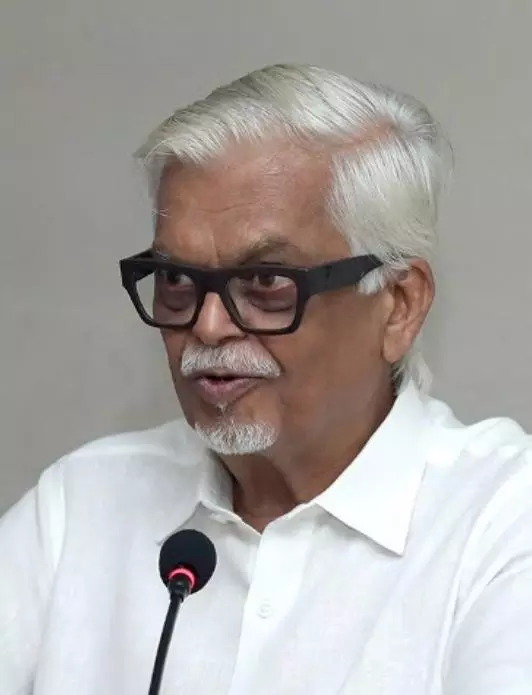

Sanjaya Baru | The other divide: E-W conflict meets N-S gap

The French could not make it due to the Covid-19 pandemic. The rest of the Permanent Five dropped in last week.

New Delhi watched the cultivated hubris of the Chinese foreign minister, the immature arrogance of an Indian American functionary of the Biden administration, and the quiet competence of the ageing Russian foreign minister.

Even the awkward British foreign secretary was in town. Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his external affairs minister S. Jaishankar must have been chuffed. Everyone wants India to fall in line.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and its special relationship with a rising China have revived Cold War memories across the Western world and given a new edge to the 20th century’s East-West divide. India is under pressure to join the so-called coalition of “like-minded democracies” in order to protect and preserve a “rules-based” global order. But the rules-based order that India seeks is one that will allow this country to sustain its economic growth, not one defined by the “either you are with me or against me” type of argument that the junior US official lobbed at India.

China observers in New Delhi remain puzzled as to why the Chinese foreign minister dropped in, but one reason could well be to figure out whether Prime Minister Narendra Modi would attend the 14th Brics Summit to be hosted later this year by China. The Brics platform offers China and Russia the opportunity to make a point to the G-7 economies. The theme of this year’s Brics summit is “Foster High-Quality Partnership, Usher in a New Era for Global Development”, India may well be tempted to shift the focus to North-South issues at a time when an East-West conflict is posing awkward choices. Brics has been dormant in recent years and may secure a new lease of life if they bring global attention to bear on development challenges facing the global South.

In the extant situation, the West has deployed the notion of “like-minded” countries based on what divides East and West. But then, there is the alternative paradigm of like-mindedness based on what divides North and South. India and other developing economies have recognised for some time now that while they have much in common with Western and Asian democracies, they have also to protect their economic and development interests, where they have to deal with challenges posed by the Western and East Asian economies.

On issues pertaining to international trade, intellectual property rights protection, carbon emissions, food security and so on, India’s “like-minded” countries are in fact mostly in the global South. While India and China have adopted similar positions on these issues in multilateral forums, their bilateral differences on trade weaken the coalition. Thus, India opted out of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) on account of its bilateral differences with China. In multilateral forums, however, India and China have agreed more than they have disagreed.

Given the inter-linkages in East-West and North-South issues, India has to chart a complex course for itself. This task has been made even more challenging by the decision of the United States and the European Union to counter Russia’s military action with economic sanctions. While Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has had grave humanitarian consequences, Western economic sanctions also have the potential to hurt well-being globally. Taken together, the Russian invasion and the Western response, through the weaponisation of trade, finance and energy flows, have exerted inflationary pressures across the globe and will certainly impact global growth negatively. This is the last knock that the world economy needed after two years of the Covid-19 pandemic.

A recent report of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (Unctad) has warned that, “in spite of calls by G-7 leaders for ‘building back a better (post-Covid) world’, separate economic worlds may in fact be rising from the ashes of 2020, with little chance of them being unified without concerted reform measures at the national and international levels… In most developing countries, fiscal and monetary expansion has been constrained largely by external factors: the limited appetite of financial markets for debt issued in local currencies, the risk of being forced into an austerity programme, should the need for IMF assistance arise, and the ebb and flow of international capital movements”.

Apart from disrupting global growth and triggering higher inflation, the post-Ukraine economic sanctions are likely to splinter the global economy into regional blocs. Already the decision to sell and buy oil in currencies other than the US dollar has had the effect of dividing the global oil economy. In many ways, the global dominance of the US dollar was on account of much of global trade, especially energy trade, being denominated in that currency. The regionalisation of trade will have serious consequences for India, which is not a member of any significant regional preferential trade group.

In the middle of this conflictual East-West and North-South situation, the director-general of the World Trade Organisation, Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, has decided to convene WTO’s much-postponed 12th ministerial conference in June. While the United States wants to debar Russia’s participation, India’s focus will have to be on the agenda items that are crucial to facilitating an increase in India’s share of world trade.

The disruption of global supply chains is creating trade bottlenecks that could impact exports and raise the cost of imports, pushing the current account deficit up.

India will have to remain firmly focused on the economy given the multiple challenges it continues to face. Market signals with respect to both private investment and consumption are still not very encouraging. External economic and geopolitical pressures would only make growth acceleration that much more difficult.

India’s priority cannot be adherence to the American sanctions. It has to be revival of economic growth.

In other words, even as war wages on in one corner of Europe, the rest of the world will increasingly have to focus on bread, butter and oil issues of immediate interest.

Reviving post-Covid global growth, getting a grip on inflation, especially the spike in commodity prices, restoring stability to the international financial payments and trade systems are the kind of issues that all the countries of the South will increasingly seek to focus on.