Brics: Brickbats and bouquets

With global economic reform no longer its focus, Brics has become more of an annual political fest.

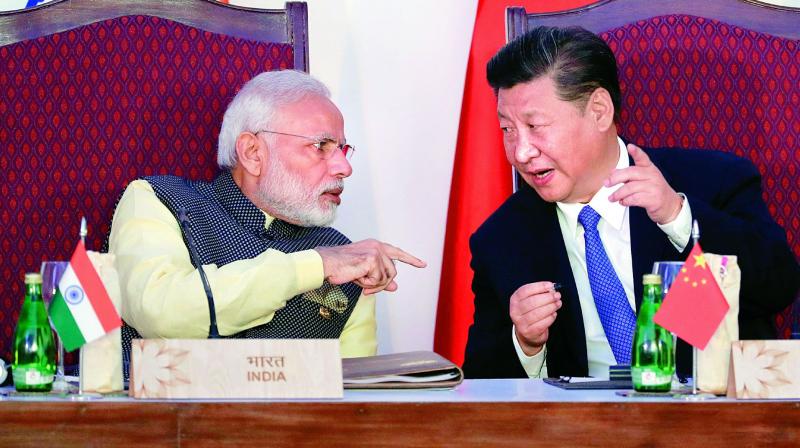

The Brics summit in Xiamen is taking place in the immediate aftermath of a confrontation between its two largest economies and nations. Till it was resolved a few days ago, it was not even sure if the Indian Prime Minister would have travelled to beautiful Xiamen, from where on clear nights one can see the lights of Taiwan. Many observers in New Delhi believe that if Narendra Modi did not take part in the Xiamen, so soon after not participating in the OBOR meeting of 28 countries, it would have meant a long-term rupture between India and China, and also cast a long shadow on the future of Brics. The last meeting between Narendra Modi and Xi Jinping didn’t exactly exude good vibes. While the Indian side was at pains to explain that the two leaders met and spoke some about important matters of mutual interest, the Chinese side quite happily administered a snub saying nothing more than handshakes and courteous smiles were exchanged. It now remains to be seen if India-China relations after Xiamen can go back to where they were before the OBOR summit?

When the Goldman Sachs economist, Jim O’Neill, coined the acronym Bric in 2001, he had in mind a list of the big and fast growing economies who would be generating the greater part of world economic growth in the first half of the new century. He gave the grouping the rather evocative Bric, suggesting a new building block in the world economy. In 2001, the G-7 accounted for 46 per cent of WGDP with just 10 per cent of the world’s population and the Brics accounted for 40 per cent of the world’s population and 18 per cent of WGDP. But economists were agreed that by 2030, Brics would account for 40 per cent of WGDP. Brics have, so far, been ahead of the curve. China and India are first and third in the world GDP (PPP) pecking order. But despite this the global financial architecture remains as before with the control in the hands of the West and mostly serving their interests. The impetus for a permanent Brics forum was the 2008 US meltdown, which demands a major reform of the world economic and financial system.

The first Bric meeting took place in 2009 and it became a formal organisation the following year. However, instead of seeking to reform the world’s economic and financial management system, the Brics began looking at itself as a political counterweight to the Western system. The addition of South Africa at the Sanya summit, a country that ranks 35 by GDP, to give the group a full transcontinental spread was a clear indication of this. Clearly, economic weight was no longer a criterion for membership. If that were so Nigeria, which is several, places higher than South Africa would have made a more eligible candidate. The big transformation of this century has been the rapid rise of China and the US-China economic relationship. Despite being its political competitor China now has a symbiotic relationship as it depends on the US trade deficit to accrue wealth. If the US ever becomes a responsible economic power, then its trade deficit should compress to well below the $502 billion it was last year. Its trade deficit with China alone is about $300 billion. Clearly, China is hugely invested in America’s profligacy and holds its US gains mostly in US banks, which finance the next cycle of US profligacy.

With global economic reform no longer its focus, Brics has become more of an annual political fest. It had become more of a platform for the summit hosts to showcase their political influence. Last year India sprang a surprise by inviting the Bimstec comprising of seven regional countries — Bangladesh, India, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Bhutan and Nepal. It was doing what Brazil and Russia had done in the previous years when they invited heads of immediate neighbours and regional groups such as Union of South American Nations (UNASUR) and Shanghai Co-operation Organisation (SCO) and the Eurasian Union.

China is now taking this one big step further by inviting Egypt, Kenya, Tajikistan, Mexico and Thailand. It is clearly casting the net far and wide as if to signal its global stature. China has also been semaphoring its intent to seek the expansion of the Brics, perhaps to give itself a larger global group to dominate. The early Brics promise of trading in each other’s currency and thus balancing bilateral trade has not happened. China clearly prefers to hold dollars rather than rubles or rupees or cruzeiros. The other big idea was the Brics Development Bank, which was the brainchild of then Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh in 2012, came to life as the New Development Bank during the Fortaleza summit in 2014 with an authorised capital of $100 billion. It is now headquartered in Shanghai with the stated task of developing “a strong pipeline of projects and responding in a fast and flexible manner to aspirations and interests of its members”. The first set of loans involving financial assistance of $811 million, to be disbursed in tranches, supporting 2,370 MW of renewable energy capacity were announced in a board of directors meeting held in Washington, ironically enough on the sidelines of the IMF and the World Bank group spring meetings. The bank is to provide $300 million to Brazil, $81 million to China, $250 million to India and $180 million to South Africa. It’s a beginning but its still a far cry from what was envisaged with only $1 billion subscribed as share capital and 99 to go. But let’s hope that is the first step leading to a new world?