Let CJI have a role to mediate on Ayodhya

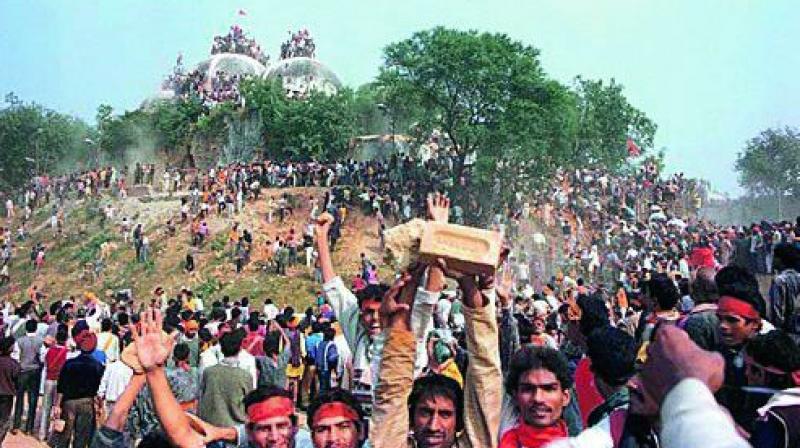

The Chief Justice of India, Justice Jagdish Singh Khehar, says he would prefer that the Ayodhya dispute be settled outside the court, mutually, between the perpetually unyielding Hindu and Muslim petitioners. The apex court is currently studying the Allahabad high court’s decision of 2010, which had insinuated that there was in fact a birthplace of Lord Ram as claimed by Hindu militants at the disputed site where the 16th-century Babri Masjid once stood. World-renowned historians and archaeologists have desisted from supporting such claims for want of basic evidence. A progressive judge was earlier dealing with the dispute for years at the Allahabad high court. He retired with his unalloyed belief that matters of faith were essentially non-justiciable in a secular court such as the one he presided over. A secular court must ideally protect everyone’s religious beliefs as well as the right to remain aloof from all of them. The Ayodhya dispute, therefore, given India’s secular Constitution put together by 85 per cent Hindus in the Constituent Assembly, boils down to a temporal standoff — the rival claims on the land in question between those who say that the mosque was arbitrarily built on what they believe to be the birthplace of Ram and those that want the courts to prevent their forcible eviction from the land on which the mediaeval mosque stood until December 6, 1992.

Justice Khehar has offered to personally mediate the complex case if accepted by the parties. There could be no doubt that the judge has offered his help with good intentions. A range of thoughts cross the mind nevertheless about why the SC would not prefer to explore a legal route and settle the case one way or another as India’s secular law mandates. A rival fact begs discussion. It is not easy to enforce the law in India, with or without the state’s patronage of rogue parties. Remember that the demolition of the Babri Masjid was carried out as a brazen snub to the SC’s authority. Its standing orders forbade any changing of the status of the disputed monument in Ayodhya. Justice Khehar has described the dispute as a sensitive issue. What happens when he retires though, as early as August this year? Will there be a mechanism backed by the SC and the government for him to continue as a mediator whose imprimatur is honoured by all when he finds a solution? And what will we do if the solution, in which he suggests a little bit of give and take, widens into a full-blown assault on law and justice as it did in 1992?

We have after all chosen to accept the route, willy-nilly, of vigilante squads and Hindutva zealots swarming through Nehru’s India. What is happening in India is a third or fourth carbon copy of what we have seen elsewhere. UP, for example, is a smudged copy of the moral policing in Iran. . There is a somewhat similar atmosphere in India in which Justice Khehar has offered to stick out his neck on behalf of reason. A less-discussed highlight of the mandir-masjid controversy is that it has created a dialogue between overtly religious parties, both garnering their constituencies with right-wing agendas that leave out India’s open-minded middle ground to worry for the future helplessly. In these days of right-wing ferment, any demand for justice does seem laughably anachronistic. If Justice Khehar can buck the trend, and prevent Ayodhya from mutating into Mathura and Kashi and a larger national inferno, India’s Muslims, as also the overwhelming majority of secular Hindus, should give him a chance. The future cannot be worse than it looks.

By arrangement with Dawn