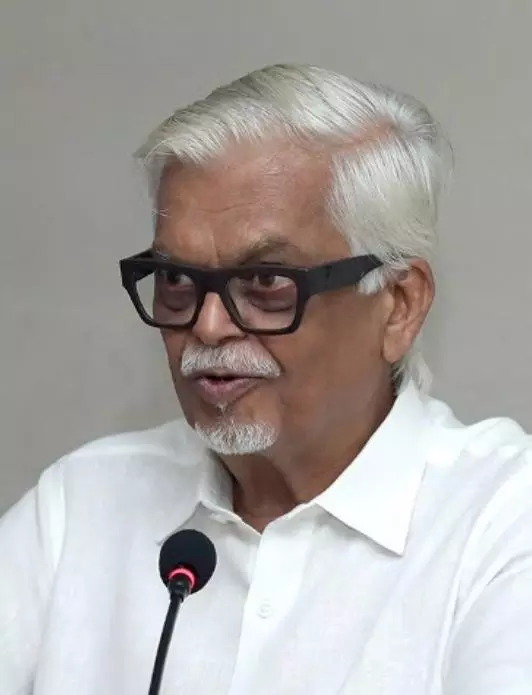

Sanjaya Baru | More ‘bang for the buck’ in defence: New thinking vital

Defence is the one area where the Union government bears full responsibility for spending and delivering results on that spending

Public discussion on the Union Budget quite understandably focuses on government spending in a range of areas that directly impact people’s lives like infrastructure, agriculture and rural development, education, health care, social welfare and so on. However, in most of these areas, the responsibility to spend and implement projects is essentially in the hands of the state governments.

Defence is the one area where the Union government bears full responsibility for spending and delivering results on that spending.

This year’s Budget papers show that total budgeted spending on defence as a percentage share of total Central government expenditure (CGE) remains unchanged at around 13.30 per cent, compared to 13.80 per cent in 2020-21 and the revised estimate of 13.35 per cent in 2021-22. Much is often made of the declining share of defence spending in gross domestic product (GDP), that is national income. However, the more relevant ratio to consider is the defence budget’s share in the total Union government expenditure.

I bear part of the responsibility for the continued misplaced focus in public discourse on the proportion of GDP devoted to defence spending. In 1999, the National Security Advisory Board (NSAB) had tasked the late Jasjit Singh (then director of the Institute of Defence Studies and Analyses, IDSA) and me (both NSAB members) to write a note on defence spending. We studied the defence budgets of several countries as well the long-term trend in India since Independence and suggested, among other things, that defence spending ought to be roughly 3.0 per cent of GDP. This number was arrived at both on the basis of the requirements of the armed forces as well as our estimate of the Union government’s capacity to spend. That number is now oft-quoted.

Defence spending did exceed this three per cent level in the years after the 1962, 1965 and 1971 wars and through the 1980s when India undertook major defence modernsation and equipment acquisition. In the decade 2000-10 two things happened that not only kept defence spending below this three per cent mark but also brought it down to two per cent. First, the improved regional security environment, with India’s relations with both China and Pakistan improving during the period 2002-2008, and the doubling of India’s GDP from $1 trillion to $2 trillion within that decade. The latter meant that even with rising expenditure, the defence expenditure to GDP ratio went down.

The defence economy has now entered a new era, with the opening up of defence manufacturing to domestic private enterprise. Renewed challenges to national security have made the armed forces leadership and defence analysts pitch for higher allocations than has been on offer. Going forward, two things matter — the success of the “Make in India” programme in defence manufacturing and the modernisation of the Indian armed forces along with the strategic reconfiguration of the role of each of the three defence services — the Army, Navy and Air Force. The Union Budget has now increased the share of defence capital expenditure earmarked for sourcing from domestic manufacturers, including the private sector, to 68 per cent of the total defence capital procurement budget.

While improving the so-called “teeth-to-tail” and “bang-for-the-buck” ratios of the Army and better equipping it for efficient high altitude and counter-insurgency engagement, the focus of the enhanced defence spending in the medium term will have to be on the Air Force and the Navy. This year’s Budget has kept this in mind, with the Air Force and the Navy securing more funds than the Army. The Coast Guard has also seen a sharp rise in its budget.

Delivering the K. Subrahmanyam Memorial Lecture under the auspices of the IDSA last week, the highly regarded strategic analyst Edward Luttwak once again emphasised the importance of the Air Force and the Navy for India’s defence preparedness, while dismissing the Navy’s demand for more aircraft-carriers.

Rather, Luttwak suggests, India should use its own land and island territories and other islands in the Indo-Pacific region as its “aircraft-carriers”. He underscored the need for new thinking about what capabilities matter and how best to acquire those capabilities.

However, a bulk of the defence procurement budget still goes into imported equipment. The progress of “Atma Nirbharata” in defence manufacture has been slow.

For this agenda to move forward quickly, greater coordination is needed between the different wings of the armed forces, defence public sector enterprises, private original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) — foreign and Indian — and the ministries of defence, industries, finance, science and technology and the state governments. This is not an easy mix to put together. However, such all-in-one coordination is required for India to finally liberate itself from external dependence on defence equipment.

India is the only major power of its size and scope with such a limited domestic defence equipment manufacturing capacity. Most countries that have such domestic capacity have been able to use wartime demand and wartime policy environments to create it. India has never lived through a long-duration war, with the last such engagement, though of limited duration, being in 1971. The Kargil war of 1999 created a security environment that helped initiate some policy change but it has taken a long time for many of the recommendations of the K. Subrahmanyam Kargil Review Committee to be implemented.

The “Make in India” programme in defence manufacturing can have positive externalities that also benefit domestic small and medium enterprises which supply components to larger entities. Many such industries have come up around Hyderabad, Bengaluru and Coimbatore. Managing this transition from importing foreign equipment to domestic manufacture has to be handled carefully given that the consumer in this market is a single entity — the ministry of defence and the armed forces. The allegations about kickbacks made in the context of imports can come up even with domestic manufacturers and there will always be the concern about crony capitalism.

A major challenge that remains for both budgeting government expenditure across the services and funding investment is the absence of a clearly defined threat perception and the role to be assigned to each of the three services as well as to new capabilities in dealing with it. An analysis of budgetary allocations can be meaningful only within such a strategic framework.