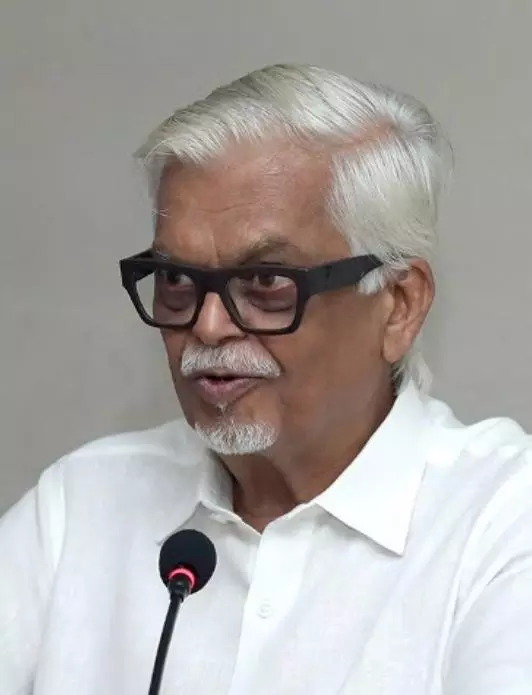

Sanjaya Baru | Secession of the successful: Their passage out of India

Every time an alumnus of my school in Hyderabad gets a prize job overseas, everyone goes gaga. Ajay Banga is the latest addition to the long list of overseas Indians, mostly citizens of their host countries, to have made it big, nominated by US President Joe Biden as the next president of the World Bank. The principal shareholders of the World Bank remain the trans-Atlantic economies. Mr Banga’s is an executive role, like that of so many bright Indian managers who run other people’s corporations.

European colonialism forced many Indians out of India, creating a global community of “people of Indian origin” (PIOs). These communities were the poor and the desperate living in some of India’s most backward regions. As writer Amitav Ghosh has recorded in his many books, the forced out-migration of indentured labour was a tragic experience of loss and hardship. The contemporary out-migration is of the well-educated, the well placed and, increasingly, of the wealthy.

I recorded in my recent book, India’s Power Elite: Class, Caste and a Cultural Revolution (Penguin, 2021), the growing phenomenon of the “secession of the successful”. Even today there are two groups of out-migrants. Those who wish to leave their home country because they cannot afford to live at home as they do, and those who wish to leave because they can afford it. The former is distress migration and the latter is the “secession of the successful”.

Journalist Vijaita Singh of The Hindu newspaper recently reported data on this “secession of the successful”, made available by the external affairs ministry in a reply to a question in Parliament. In 2022, she reported, over 2.25 lakh Indians renounced their Indian citizenship. It was reportedly the highest ever since 2011. Most interestingly, a large number of them are what financial analysts and bankers refer to as “high net worth individuals” (HNIs). HNIs are those who have wealth of over $1 million or Rs 8.2 crores. Singh quotes a Henley Global Citizens Report that shows there were 3.47 lakh such people in India in December 2021. Of these, 1.49 lakh HNIs were found in just nine cities -- Mumbai, Delhi, Kolkata, Bengaluru, Hyderabad, Pune, Chennai, Gurgaon and Ahmedabad. According to the report, India ranked fourth in the world in terms of privately-held wealth, after the United States, China and Japan. A growing number of Indian corporate families are now relocating overseas, at least partly in search of the “ease of doing their business”.

Admittedly, the HNI is defined in monetary terms, but if we were to also define a separate category of HNIs in terms of their academic attainment, then the numbers would be even more. Sadly, though, most schools that boast about the achievements of their alumni, both overseas and in India, track their wealth, corporate status, political power and celebrity value, but few focus on their academic achievements.

Being made aware of the phenomenon of out-migration does not imply that one can easily counter it. The economics of the phenomenon is embedded both in the dynamics of development and politics in the home country and in the demographic dynamics of the host country. The former contributes to the “push” effect and the latter to the “pull” effect.

The decline in population growth in developed industrial economies, with their becoming ageing societies, has induced many of them to open up to in-migration.

Such in-migration covers the entire spectrum of class -- with countries as diverse as the United States, Dubai (UAE) and Australia inviting skilled industrial and construction workers, on the one hand, and on the other, highly talented scientists, engineers, doctors and other professionals.

While the English-speaking world has attracted most Indians so far, the pressure of demographic change in all developed countries is forcing non-English speaking countries like Japan and in Europe to also seek in-migration from India.

The Indian middle class, ranging from the lower economic end of skilled workers to the high end of qualified professionals and even business persons, are more welcome in most countries because Indians tend to get easily adjusted to their new social environment.

In India, there has also always been a “push” effect that encourages out-migration, but in recent years this has become more compelling. Rising social and political tensions, the difficulties of daily life in urban and semi-urban centres, institutional corruption and discrimination of various sorts are all encouraging out-migration. The recent news report of four Gujaratis being frozen to death while trying to illegally cross the Mexican border into the United States drew attention to distress migration even from a developed state like Gujarat.

At least one institution and one company is preparing for the continued exodus of Indians overseas. For starters, educational institutions are increasingly offering courses that make it easier for students in India to go overseas. While the Union government has allowed foreign universities to open campuses in India in the hope that this would encourage youth seeking overseas education to stay home, they may in fact be viewed as helping prepare them for employment opportunities overseas. In any case, the rising demand for overseas education is in fact the other side of the coin of a rising desire to migrate.

The company that is preparing for the future is Air India. Its recent order to buy over 50 wide-bodied long-haul aircraft is based on the assumption that the traffic between India and distant destinations in the United States, Canada and Australia will only increase. Why allow the West Asian and European airlines to cash in on this potentially growing market? In the not-too-distant future there would be direct flights from a dozen or more Indian cities to destinations around the world. The passage out of India would be fast and comfortable.

The Nobel Prize-winning economist Milton Friedman told Jawaharlal Nehru that the US grew by attracting talent from around the world while India should plan for growth by converting its huge population into the world’s largest pool of talent. What neither may have imagined is that this talent pool of a developing economy would in fact feed the growth of developed economies.