Hostility to referendums will worsen matters

And I get the urge for going, sang Joni Mitchell more than a half-century ago, When the meadow grass is turning/ And summertime is falling down. That sentiment has been echoed in recent days in two very different parts of the world.

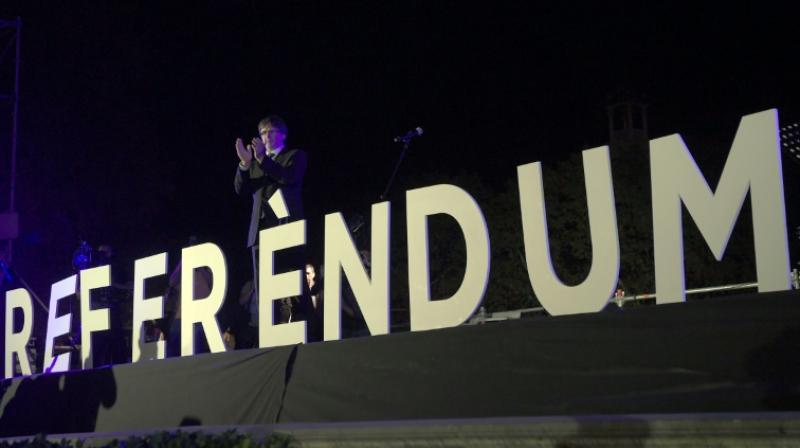

Last Sunday’s contentious referendum in Catalonia was preceded six days earlier by an equally controversial vote in Iraqi Kurdistan. In both cases, the longing for independence goes back a long way. And in both cases the states from which the Kurds and Catalonians wish to separate have reacted in a manner that is likely to exacerbate tensions. The disturbing scenes witnessed in Barcelona as a massive police force deployed by the authorities in Madrid sought to thwart the Catalonian vote, and more generally the belligerent attitude adopted by the conservative government of Spain’s Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy, can only serve to fuel regional passions. Perhaps not entirely fairly, the repression evoked memories of the Franco dictatorship, which 80 odd years ago snatched back the autonomy that Catalonia had secured.

It was only four decades later that the region was able to re-establish its right to manage its own affairs. A substantial number of Catalonians consider that insufficient, and the sense of injustice has grown since the financial crisis of a decade ago. Catalonia is considered a relatively well-off region in the Spanish context, but the Rajoy government has gone out of its way to undermine its aspirations. Catalonian leader Carles Puigdemont holds the view the recent referendum provides an adequate basis for a unilateral declaration of independence. Madrid, meanwhile, has threatened to invoke a hitherto unused clause of the Spanish Constitution to suspend regional autonomy. The Spanish state’s reaction detracts from its moral authority. Further, it’s hard to take seriously Rajoy’s insistence on altogether ignoring the referendum, partly on the basis that it had been ruled illegal by the highest court in the land. The Kurdish bid for independence from Iraq has also received little international backing, including from those who effectively set the region on its way by guarding its autonomy against Saddam Hussein after the 1991 Gulf war. Within West Asia, only Israel has backed the idea of an independent Kurdistan, for strategic reasons of its own. Conversely, there have been threats of military action and economic sanctions from not just Baghdad and Tehran but particularly vociferously from Ankara.

Recep Tayyip Erdogan had hitherto been reasonably chummy with the Iraqi Kurds, in contrast to his attitude towards the Turkish and Syrian segments of the Kurdish population. The Kurds are the world’s largest ethnic group without a national homeland, of which they were deemed unworthy when the British and French colonial powers carved frequently incoherent boundaries across West Asia following the defeat of the Ottoman Empire. The case for an independent Kurdistan has existed ever since, with the Kurdish minority besieged, or used as strategic pawns, to varying degrees across four states. Turkey and Iran are particularly ill-disposed towards the idea of sovereignty for Iraqi Kurds primarily because they fear the effect it would have on their respective Kurdish minorities. Massoud Barzani, head of what is effectively a family firm at the helm of the Kurdish regional government, has thus far not hinted at a unilateral declaration of independence, even though the referendum, again with an affirmative vote of around 90 per cent, is on various scores more credible than its Catalonian counterpart. In both cases, there was scope for serious-minded political negotiations to pre-empt a crisis, whereas a belligerent response can only strengthen the urge for going. There’s a crucial lesson in this for many nations, not least Pakistan in the Baloch context.

By arrangement with Dawn