Afghanistan is not headed towards peace after US exit

In the light of the recent negotiations in Doha between the United States and the Taliban, there has been much talk about peace returning to Afghanistan after four decades of more or less continuous war.

That is an extraordinarily long stretch by any measure, less than half of it taken up by the American invasion that began in October 2001 — which alone makes it the longest war the US has waged. And, after all these years, Washington appears to be preparing to hand back the initiative to the very forces it dislodged almost 18 years ago.

There can be no question the Afghan Taliban regime that began consolidating its power in the mid-1990s was atrocious in every sense of the word. And it did indeed harbour Osama bin Laden and his Al Qaeda outfit, after Sudan failed to interest Saudi Arabia in taking responsibility for an unwanted guest. But the Taliban had nothing to do with 9/11, and even senior Al Qaeda operatives were reportedly uncomfortable about what the “aeroplanes plot” would portend for their hosts.

Since some form of revenge was inevitable after the September 11 terrorist attacks, a special forces policing operation targeting Tora Bora might have achieved its goal. But George W. Bush had dumbly declared that no distinction would be made between terrorists and those who harboured them, and Barbara Lee was the only member of Congress who warned against embarking on “an open-ended war with neither an exit strategy nor a focused target”.

Of course, October 2001 was not the first time the US had intervened in Afghanistan. It was providing succour to the incipient mujahideen months before the misguided Soviet invasion of December 1979. The strategy was masterminded by Jimmy Carter’s national security adviser, Zbigniew Brzezinski, an incorrigibly bloody-minded cold warrior whose primary concern was to humiliate the Soviet Union by luring its forces into an unwinnable war.

Challenged on this score by the French newspaper Le Nouvel Observateur 20 years later, he responded: “The secret operation was an excellent idea. Its objective was to lead the Russians to the Afghan trap, and you want me to regret it? … What is the most important thing when you look at world history, the Taliban or the fall of the Soviet empire? Some overexcited Islamists or the liberation of central Europe and the end of the Cold War?”

“Some overexcited Islamists” continue to occupy America’s attention decades after it provided them with the means to combat the foreign invaders it had helped lure into Afghanistan. The US also provided manuals that included advice on slitting the throats of, for instance, “communist” teachers who worked in coeducational schools. It was all for a great cause, naturally, but who can seriously deny that the Taliban are effectively the illegitimate offspring of a sordid ménage a trois involving Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and Uncle Sam?

The aims of the Soviet invaders in 1979 and the American ones in 2001 overlapped in some ways, but both interventions were grievous follies and Afghans have paid the price ever since. The prospect of peace at last is inevitably exciting, but can it seriously be achieved if the Taliban are enabled to share power in Kabul?

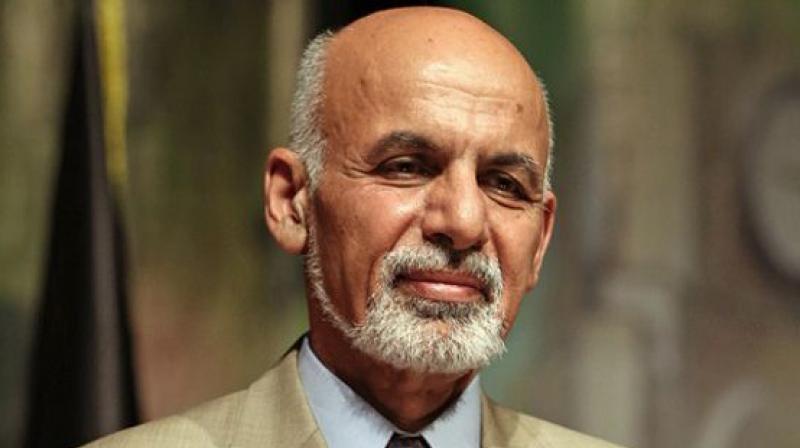

The government of Ashraf Ghani has not been involved in talks thus far, and the President’s apparent desperation to persuade US/Nato troops to stay on for the time being no doubt feeds into the Taliban perception of him as a Western puppet. There is no saying what lies ahead, although many segments of society — especially women — would be horrified at the idea of the Taliban re-establishing their obscurantist rule. Afghanistan would have been ultimately better off without any foreign intervention. Sure, the Saur inqilab of 1978 might have proved to be short-lived, but then it never made much headway outside urban centres. If overtaken by a rural rebellion, it may have left behind seeds for a future transformation.

What tomorrow might bring cannot be foretold, and it could be a long time before Afghanistan breathes the free air that its most optimistic sons and daughters can already smell. A likely precondition for that, though, is the complete cessation of foreign interference, whether by Pakistan and the Gulf states that help to prop up the Taliban, or by India and the West.

In the short run, though, the prospect of a Taliban return to even partial power in Kabul is unlikely to bode well for Afghans.

By arrangement with Dawn