Sanjaya Baru | Restoring confidence is key to economic growth

The upward movement in stock market indices, claimed Union finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman, in response to a Parliament question last week, "is driven primarily by expectations of future economic growth." Quite understandably, the FM attributed these positive expectations and the market sentiment to government policy. Having made that confident assertion Ms. Sitharaman went on to reassure Parliament that the government, the central bank and the stock market regulator are all monitoring market indices to "ensure orderly functioning of the stock markets and maintain macro-financial stability."

Market analysts take a more nuanced view. Some see portfolio inflows from a global economy awash with easy money, thanks to President Joe Biden's fiscal liberalism, fueling market engines in India. Shying away from China for geopolitical and economic reasons they are coming to India, among other emerging economies. Others believe that the Reserve Bank of India's monetary policy, with low rates of interest at a time when inflationary expectations are rising, is encouraging investors, big and small, to chase equities. The rise in valuations does not necessarily correspond to trends in the real economy. Indeed, even Ms. Sitharaman has focused on 'expectations' rather than 'performance'.

Over the years Union finance ministers have had to swing between claiming that they "do not lose sleep" over fluctuations in market indices, as Dr Manmohan Singh famously did in his days as finance minister, to claiming credit for what may well prove to be, with hindsight, 'irrational exuberance." It is not at all surprising that Ms. Sitharaman chose to be so bold as to claim credit for the sentiment on Dalal Street. After all the Union government has been desperate to get hold of some positive economic indicators so as to boost investor and consumer confidence.

The ride has been rough for Ms. Sitharaman. Despite her best efforts, and visible results on the fiscal front, both investment and consumption remain subdued due to persistent modest expectations about the near term. The Reserve Bank of India's consumer and business confidence surveys continue to suggest that both firms and households are not yet voting for the future even as there is an improvement in both contemporary sales and capacity utilisation. There is a post-lockdown recovery but it is distinctly K-shaped, indicating a widening gap in income and expenditure between the upper classes and the masses.

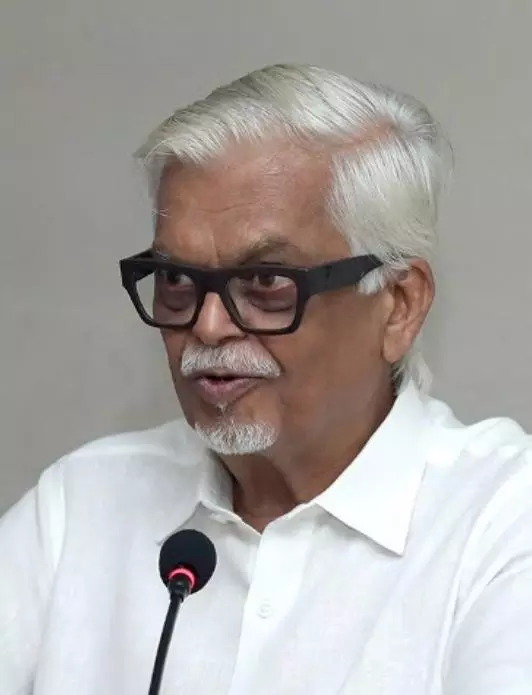

The economic and financial analyst, V. Anantha Nageswaran, a member of the Prime Minister's Economic Advisory Council, has recently written on his widely read and highly regarded blog,(thegoldstandardsite.wordpress.com/author/jeevatma/),"If India manages to grow its real GDP by 5% and nominal GDP at 9% between 2021-22 and 2029-30 and assuming a USD/INR exchange rate of 70, India's real GDP will be USD3.0 trillion and nominal USD6.7 trillion by the end of the decade." Of course this statement skirts the fact that the economy will not be USD5.0 trillion in 2024, a goal set by Prime Minister Narendra Modi in 2017, when India's GDP in fact began approaching the USD3.0 trillion mark.

This line of thinking is also reflected in the views of another member of the PMEAC, Sajjid Chinoy, who has recently written that exports and public investment will have to drive economic growth in the near term given subdued sentiments of firms and households. "All told", concluded Mr. Chinoy, "exports and public investment will need to create a growth and jobs bridge until private investment and consumption recover."

The Union government has been trying to push public investment but fiscal constraints have been imposed on it by slower growth. The slow progress of privatisation of public sector enterprises has also posed a challenge. In some traditional sectors of public sector spending, like defence production, the government is hoping private investment will in fact make up for inadequate public investment. In the short term increasing public investment is not merely a fiscal challenge. It is even more an administrative challenge. Even the chief of army staff recently bemoaned the constraints imposed by bureaucratic inertia on public spending.

There has been some good news on the export front with a 74% jump in exports in the first quarter of 2022 over the 'first lockdown' quarter of 2021. Not surprisingly, Prime Minister Modi has sought to associate himself with this good news by chairing a meeting with representatives of export firms, trade promotion councils and Indian diplomats overseas where he set a target of USD400 billion for this year's total exports.This compares with the USD291 achieved in 2020-21 and USD313.5 attained in 2019-20.

While firms and diplomats can do their bit to push exports, the ministry of finance and commerce will have to play their part too in terms of addressing exchange rate and tariff policies. As part of its Atmanirbharata strategy and in seeking to contain Chinese imports the Modi government aligned its trade policy against imports in general. The global experience shows that any strategy to push export growth has to be aligned with a country's import policy. All major exporting economies are also importing economies. Given the structure of Indian exports, and the commodity pattern of the recent surge, this link is all the more relevant.

While the external affairs minister has been actively reviving free trade talks with the European Union, Australia, Britain and so on, the commerce minister has stopped criticising the United States, Japan, Korea and the South-east Asian Nations on trade imbalances. To top it all, trade with China is again rising albeit below the radar of BJP's swadeshi manch. India's exports to China grew by close to 70% in the first half of 2021, even though the trade deficit remains significantly high.

After spending its first term in office criticising the Manmohan Singh government's trade policy, the Bharatiya Janata Party has quietly come to terms with the necessity of external trade policy moving from inward-orientation to outward-orientation. In a democracy policy change is more often than not a product of necessity rather than choice.