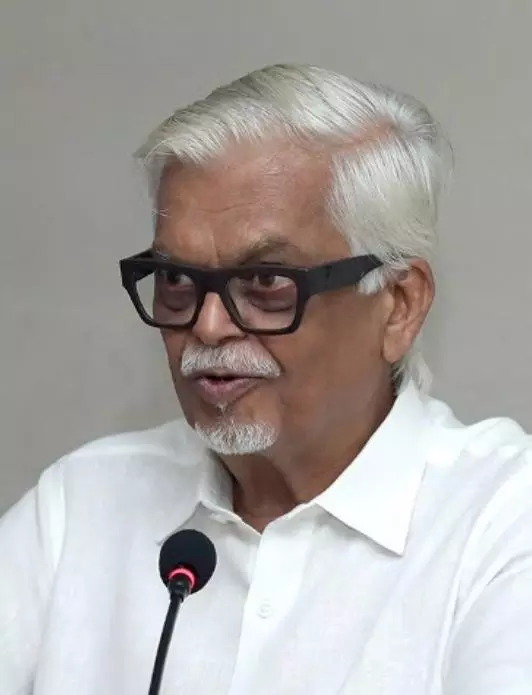

Sanjaya Baru | Shinzo Abe's role was key in normalisation of Japan

Over the weekend Japan and much of the world commemorated the first anniversary of the tragic assassination of Shinzo Abe, the longest-serving Prime Minister in Japan’s history and the most consequential leader of post-war Japan. Shinzo Abe was not just a great son of Japan but also a highly regarded Asian leader and an internationally respected statesman. Above all, for us, he was a true friend of India.

He re-energised a nation that had begun to stagnate through the 1990s, shaped the geopolitics of the Indo-Pacific region and laid the economic, social, political and security foundations for the emergence of a “New Japan” in the twenty-first century.

Not surprisingly, therefore, Shinzo Abe’s shocking assassination on July 8, 2022 has been widely mourned in Japan, in India and around the world. To recall and record his singular contribution to what I call the “normalisation” of Japan, I invited a few Japanese and Indian scholars to contribute essays for a volume that has just been published. This collection of essays, The Importance of Shinzo Abe: India, Japan and the Indo-Pacific (HarperCollins, 2023) is a record of Abe’s historic legacy.

Abe’s special equation with India has many dimensions. His grandfather, Prime Minister Nobusuke Kishi, was welcomed in New Delhi by Jawaharlal Nehru with great fanfare that deeply touched the psyche of post-war Japan. India was among the first free nations to establish diplomatic relations with post-war Japan.

China, South Korea and many Southeast Asian nations had initially poor relations with post-war Japan, given the history of Japanese imperialism in the region. India stood out as a friend.

While Japan’s citizens became avowedly pacifist after the experience of being the only nation to have suffered a nuclear attack, there was a brief period in the 1980s when Japanese elite sought to reassert their presence and personality. It was at this time that Shintaro Ishihara and Akio Morita co-authored the famous polemical tract, The Japan That Can Say No (1989), in response to Western bullying and attempts to put a lid on resurgent Japan. The United States had imposed draconian trade restrictions on Japanese imports and the European Union cited competition from Japan as the reason for creating a “single market”. Yet, Japan remained a subdued geopolitical power, content with being the world’s second biggest economy.

The economic stagnation of the 1990s and China’s rise after 2000, overtaking Japan to become the second biggest economy, woke Japan up to the reality of a new power play in Asia. This writer was part of a high-level delegation sent to Tokyo by the government of Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee to explain to a miffed Japan why India had conducted nuclear tests in 1998. By 2006, when Prime Minister Manmohan Singh signed the nuclear deal with the United States, Japan had come around to accepting and sharing India’s security concerns.

It was Prime Ministers Manmohan Singh and Junichiro Koizumi who in 2005 first initialled a strategic partnership between Asia’s two great democracies. However, it was Prime Minister Abe’s 2007 visit to India, and his historic address to the Indian Parliament on what he termed the “Confluence of the Two Seas -- Pacific and Indian Oceans”, quoting Dara Shikoh, that defined the new phase in the bilateral relationship.

At present, Japan is among the few countries with which India has a virtually problem-free and productive bilateral relationship. Abe is to be credited for this.

He was not only the architect of a new Japan-India relationship but also the principal visionary behind two major geopolitical ideas of our time in Asia – the “Indo-Pacific” and the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue – otherwise known as the “Quad”. India’s external affairs minister S. Jaishankar -- who knew Abe well -- notes in his preface to my book that: “If there is a single individual who can be associated with the emergence of the Indo-Pacific as a strategic reality and the Quad as a cooperative platform, that is unquestionably Prime Minister Abe.”

Tomohiko Taniguchi, a former special aide to Prime Minister Abe and one of the authors in my volume, says that Abe regarded Dr Singh as his “mentor” and Prime Minister Narendra Modi as a “close friend and partner”. Taken together all these are adequate reasons for the initiative I chose to take in editing this volume paying tribute to Shinzo Abe.

But there is another reason as well. In the standard international relations literature in both countries, heavily influenced by Western scholarship, there is an overwhelming tendency to view the India-Japan relationship merely through the prism of Big Power rivalry in Asia, that is the China-US rivalry. While both Japan and India have shared concerns about China and share a friendship with the United States, there is a far more important historical factor defining India’s view of Japan.

From Swami Vivekananda and Rabindranath Tagore, to Mokshagundam

Viswesvarayya and Jawaharlal Nehru, the intellectual leaders of India’s national movement were inspired by Japan’s example of being the first industrial nation in Asia that also successfully defeated a European power, namely Russia, in 1905. All four of them wrote eloquently about the need for India to learn from Japan. It is not surprising at all that by the 1940s Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose chose to go to Japan in search of support for the cause of India’s liberation.

Post-War Japan turned excessively pacifist, and came to accept Western dominance in world affairs far too easily and sought security in a US nuclear umbrella. The brief moment in the 1980s when there was a “Japan that could say no” passed too quickly. Funked by China’s rise Japan was beginning to keep its sights low. Shinzo Abe changed that, seeking the normalisation of Japan’s status as an Asian nation, campaigning for a change in the country’s Constitution to enable the re-arming of Japan.

Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s new security and defence policy initiatives have been made politically possible in Japan thanks to the groundwork that had been laid by Abe. Hopefully, Japan’s new leadership will reinforce Japan’s independent personality, as Shinzo Abe sought to, and not retreat into the comfort of remaining an occupied nation.