Films & feelings

The furore over the film Padmavati reveals a poor state of affairs. It draws on what happened after Sultan Alauddin Khilji’s siege of a Rajput kingdom at Chittor in 1303. Accounts vary, as Prof Divya Cherian recounted in an article in an English daily: “There is no historical evidence that there was such a figure in Chittor when it was besieged, or that desire for a beautiful woman (Rani Padmavati) played any role in Khilji’s interest in conquering the fortress.” Sufi poet Malik Mohammad Jayasi wrote the poem Padmavat in 1540, in which Khilji storms the Chittor fortress, only to find her ashes. She had committed sati on her husband the king’s death in the battle. By the 18th century, the tale was recast to emphasise Khilji’s Muslim identity in a clash between the Rajputs and the sultan; and “the resistance of Hindus” to Islam.

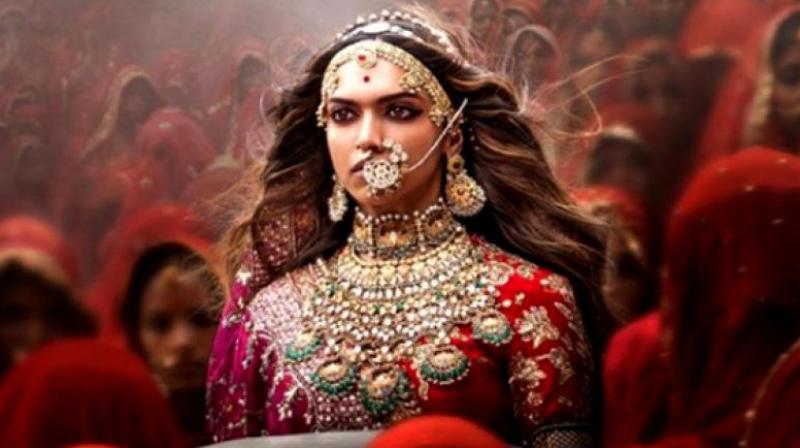

This explains why three state governments banned it. Freedom of speech is subordinate to popular sentiment. The chief convener of the Rajput Karni Sena called the film “cultural terrorism”. A senior functionary threatened actress Deepika Padukone with physical harm. A Uttar Pradesh outfit announced a bounty of five crore to anyone beheading her and the film’s producer Sanjay Leela Bhansali. The Supreme Court refused to stay the release of the film, which was due on December 1, as the Central Board of Film Certification had yet to make a decision. Its chief, Prasoon Joshi, said that it had returned the movie to the producer without certification because “the paperwork is not complete”. The reason he cited reveals the rot in the system for which the court must share the blame: “The very disclaimer, whether the film is a work of fiction or a historical (sic), was left blank and not stated”. The producer was asked “to provide important documents”. He did not specify which.

Is it anything but historical illiteracy to allege “distorting history” of one who never existed? Public discourse has all but wiped out the very concept of historical fiction; fiction based on history while retaining its character as fiction. The damage was done by the Supreme Court nearly 30 years ago, when actor Amjad Khan made a TV serial based on the historical novel The Sword of Tipu Sultan by Bhagwan S. Gidwani for Doordarshan. All hell broke loose, and in response Doordarshan decided gratuitously to disavow any claim to historical accuracy or authenticity, as if such a disavowal was called for.

The court went one better. Disposing of a special leave petition seeking a ban on the serial in February 1991, it directed that the following announcement be made along with the telecast of each episode: “No claim is made for the accuracy or authenticity of any episode being depicted in the serial. This serial is a fiction and has nothing to do either with the life or rule of Tipu Sultan. The serial is a dramatised presentation of Bhagwan Gidwani’s novel.” Poor Prasoon Joshi, a lyricist, followed this judicial fiat.

There is no sanction for this in the Cinematograph Act, 1952. The court upheld it in 1970 only on the government’s assurance that there would be “experts sitting as a tribunal and deciding matters quasi-judicially”. A tribunal was set up in 1983 but its head, a retired high court judge, holds office “during the pleasure of the Central government”. This holds good for everyone — the chairman and members of the CBFC, members of the advisory panels, the examining and revising committees. It is a huge farce.

If this be the treatment of historical fiction what may we expect of political parodies of the political class? We have regressed. There was no such criticism of Sohrab Modi for his films Pukar (on Emperor Jehangir) or Sikandar-e-Azam (on Alexander) and umpteen such films. The Supreme Court laid down the law in such cases concerning a film with a highly political theme, Ore Oru Gramathile, which attacked the policy of reservations on the basis of caste rather than economic backwardness. It sternly rejected the Tamil Nadu government’s plea that it would create a “law and order” problem. “What good is the protection of freedom of expression if the state does not take care to protect it? ...(F)reedom of expression cannot be suppressed on account of threat of demonstration and processions or threats of violence. That would tantamount to negation of the rule of law and surrender to blackmail and intimidation... Freedom of expression which is legitimate and constitutionally protected cannot be held to ransom by an intolerant group of people”. This was said in 1989. The apex court has not spoken in this vein since.

By arrangement with Dawn