An opportunity called Independence: Use it

There is something universally uplifting about independence — be it for a teenager, a city, a village, a province or an entire country. Coming into your own is empowering. But only if opportunities exist to break free of the inevitably skewed nature of endowments and constraining regulations.

Modi 1.0 promised a restart to a jaded electorate. The implementation of the Goods and Services Act, via the collaborative Union plus state government-owned GST process, was the high point of progressive, cooperative federalism in 2017. Conversely, the “reverse direct action” to integrate Jammu and Kashmir into India on August 5-6 this year, was the low point, which breeds apprehensions.

First, will the status of English be demoted from being one of the two languages in which the Union government functions? The Constitution specifies that Hindi is the “official language” of the Union. English has survived because Parliament extends the timeline for linguistic diarchy to end.

English is being steadily eroded by attrition as individual states focus on developing their own languages — there are as many as 22. The digital revolution helps. Apps now provide instant translation of content — admittedly still of dodgy quality but getting better every day — across multiple languages. Soon online, digital, real-time translation services might remove the tedium of learning multiple languages and render translators redundant.

English remains the language of the traditional elites and the aspirational neo-elite, as also an easy link with the rest of the world. But Bollywood is steadily making Hindi a domestic link language. The real question is, does Modi 2.0 have the patience to let attrition work through to the demise of English, or shall it fast forward an existing trend, as it did the ongoing integration of J&K?

Second, can the August 2015 agreement — not yet made public — between the Union government and the National Socialist Council of Nagaland deliver the symbols of autonomy that it is rumoured to extend on the erstwhile J&K pattern? Doing so would demonise the J&K policy as discriminatory and anti-Muslim, since civilian recourse to violent extremism is at the heart of both problems.

Third, the BJP controls 10 large and five small states, out of 26 states and three Union territories with legislatures. Further gains, which are likely, will make it a domestic, political superpower, possibly threatening the survival of democracy, as a value, ensuring diversity and choice.

Alternatively, could an extended period of single-party dominance — as experienced earlier from 1951 to 1977, and 1980 to 1989, both times under the Congress Party — be beneficial rather than malign? Extended mandates encourage political parties to pursue their core mandates — as the BJP is doing today.

The periods of dominant and sustained Congress rule revealed its centralising tendency and elitist compact with marginalised communities, which generated a pushback from regional, middle caste and Hindu aspirations, leading to its decline.

Modi 1.0 came to power on a mandate for public integrity and development but used the opportunity to probe the resonance of its core nationalist, Hindu-first agenda. Shall Modi 2.0 go further and open the hitherto deliberately ignored Pandora’s boxes — the role of a primarily private sector-led competitive economy; curbing crony capitalism; articulating the limits of autonomy for the minorities and an envelope for federalism, which does not distort national markets for land, labour and capital or undermine individual merit as a core metric.

Social progress and harmonising adjustments are about peeling away embedded public hypocrisy. Swearing allegiance to the high morals articulated in our Constitution which do not align with reality is one such.

Why is a makeover of the political environment and architecture necessary? The “adrenalin rush” from “freedom” and democratic success dissipated fairly quickly after the Bandung Conference in 1955, in which India was a key participant and advocate for Afro-Asian anti-colonial solidarity. The population cohorts which imbued this heady idealism are now in their dotage and represent slightly more than seven per cent of our population.

Others, born between 1960 and 1985, lived through a fraught period starting with a humiliating defeat in the 1962 border war with China and famine in the early 1960s; two short wars with Pakistan in 1965 and 1971 which redeemed our honour but destructed our economy. Living through economic isolation and State dominance in the early and mid-1970s even as Japan, South Korea and Southeast Asia were dialling back closed borders, resulted in erosion of India’s international standing and the worsening of domestic well-being.

This “beleaguered” generation of Indians, caught between the idealism of past generations and their own unfulfilled aspirations, are around one-fourth of our population. They are also the key decisionmakers currently in the government, economy and civil society. It is they who have shaped the India of today, with its warts and all.

Two-thirds — the “New Age” Indians — were born after 1985 and grew up in a rapidly integrating world, following the collapse of the Berlin Wall. Aspirational India acquired a nuclear weapons capability and fought a triumphal high-altitude conventional war in Kargil against Pakistan; battled worsening levels of internal militancy and in short succession, the assassination of two of India’s Prime Ministers, and suffered post-2011 from the winding down of the virtuous international consensus on open international trade and capital flows, which had lifted all boats.

At home, a thin layer of the meritocratic elite and a larger band of the middle class was spawned by domestic liberalisation and economic reform, at ease in their desi-ness; unashamed of their indifferent English, their craving for dal-chawal, dosai-rasam, dhokla or maach-bhat, their self-confidence boosted by their international competitiveness.

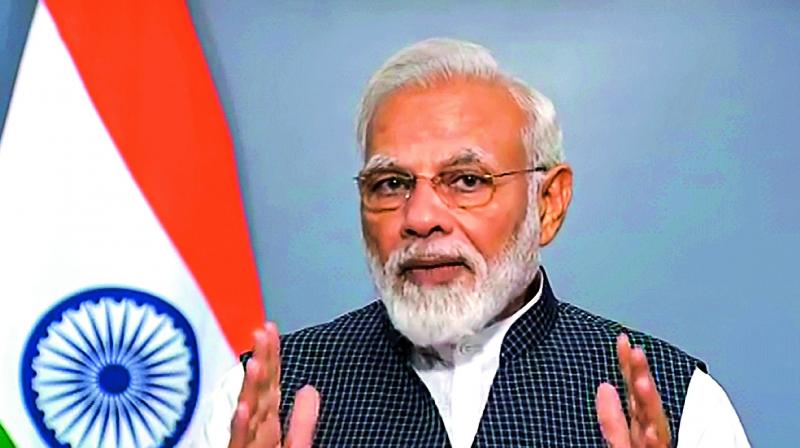

Prime Minister Modi speaks directly to this set of Indians who are tomorrow’s leaders. It is they who have to use the opportunities made available by “Independence” to resolve the accumulated contradictions in our polity and determine trade-offs between (a) free choice and property rights versus regulation and State domination — currently the latter is winning; (b) merit versus entitlement — currently the latter is winning; (c) equity, human rights and sustainability versus rapid economic growth — the former is winning; (d) a diverse, open society and economy versus domestic integration and international autarchy — the latter is winning; and (e) choose between the Rule of Law and rule by law — the latter is winning. How we choose will determine who we become.