Need focus on increasing political bias of news leaks

The UK foreign office last week hosted a global conference on press freedom, which saw 60 ministers from around the world and hundreds of journalists gather to champion independent journalism and reiterate its criticality for democracy.

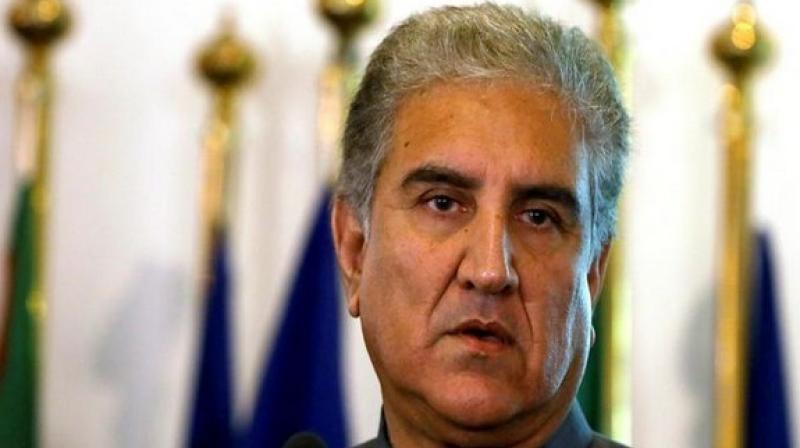

The conference caused a buzz in Pakistan because of videos on social media showing Shah Mehmood Qureshi addressing a large hall of empty chairs, perceived as an international critique of the State’s crackdown on free media. It also made headlines in the UK for exposing the government’s hypocrisy: On the same day that the conference kicked off, Britain was defending itself in a case brought by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism along with other human rights organisations over UK intelligence agencies’ mass surveillance of citizens, including journalists’ communications.

These events unfolded alongside the political storm stirred by the publication of the former UK ambassador to the US’ leaked diplomatic correspondence. The ambassador, who described the Trump administration as “dysfunctional” and “inept”, became the focal point of both growing UK-US tensions and toxic Brexit politics within the UK. And while participants in the foreign office conference defended media freedom, the metropolitan police threatened to prosecute journalists who publish leaked information.

Meanwhile, in Pakistan, political dynamics were thrown further asunder with a different kind of leak: that of videos allegedly showing accountability court judge Arshad Malik claiming he was pressurised to convict Nawaz Sharif. While not a leak in the classic sense — there was no leak of classified government information — the videos raise the same questions as more typical news leaks, with similarly vital political implications.

Leaks lie in the murkiest space within the intersections of democracy, State sovereignty and press freedom. Nothing about leaks is clear-cut. Most countries have laws explaining when leaks are illegal, usually when the classified documents could undermine national security. But much legislation is vaguely worded; for example, the Official Secrets Act, under which the source of the leaked diplomatic correspondence could be prosecuted, talks of “damaging disclosure” that could “endanger the interests of the United Kingdom abroad”. In many cases, however, the accountability argument trumps other considerations. The low prosecution rate of leaks in mature democracies such as the UK and the US points to the complexities around this kind of information flow. Sources are difficult to identify, prosecution would often entail the release of additional sensitive information and, more relevantly, governments prefer to remain lenient on leaks because they are a tactic purposefully used by officials as a strategy to share information and test ideas with the opposition and wider public.

In a post-WikiLeaks, digital world, news leaks are an integral part of the information landscape. And they throw up serious challenges for journalists. Reporters who receive leaks have to weigh the legality of publishing information, its implications for national security, its reliability and verifiability, and its newsworthiness in light of the public interest.

But increasingly, journalists must weigh whether the leak is in service of an explicit political agenda. In the cases of both Kim Darroch, the UK ambassador to the US, and Malik the answer is yes. Darroch is known to be in favour of the UK remaining within the EU, and the journalist who published the leaked information is well connected with hard-line Brexiteers. There is much speculation within the UK media that the leaked diplomatic correspondence is a warning to pro-EU civil servants not to jeopardise Brexit. In Malik’s case, the leaked videos’ role in tussles between the PML-N and the PTI government as well as the establishment more broadly is obvious.

The increasing political bias of news leaks is a dimension that needs greater focus. Leaks increase when States and governments function poorly; when politicians and government officials are unable — owing to political dynamics, fear or expediency — to openly debate critical policies. Leaks become the recourse when other dynamics, such as political polarisation and creeping authoritarianism, begin to undermine the workings of democracy. It seems we should focus less on the leaks and the journalists who publish them, and more on the underlying political drivers for them.

By arrangement with Dawn