Remembering Red Rosa: The inspiration' behind Lenin?

Ten years after she was callously murdered in Berlin, on the night of Jan 15-16, 1919, the German poet and playwright Bertolt Brecht captured the essence of Rosa Luxemburg’s unceremonious end in this epitaph.

She and her comrade Karl Liebknecht were hunted down together and killed separately on the same night by members of the Freikorps, which would transmute into Adolf Hitler’s Storm Troopers. It wasn’t a Nazi regime, though, that presided over the elimination of the two revolutionaries. Rather, it was one led by the German Social Democrats (SPD), a party whose radical left wing Luxemburg and Liebknecht had long dominated.

It was the great European conflagration that brought matters to a head. The vast bulk of the SPD capitulated to the nationalism of the day. Liebknecht was the only SPD member of the Reichstag who voted against war credits, and was branded a traitor for his principled stance. Luxemburg summed up the stance of her party, which still traced its lineage to Karl Marx, along these lines: “Proletarians of the world, unite in peacetime but slit each other’s throats in wartime.”

In the period preceding the First World War, ‘social democrats’, in common parlance, were indistinguishable from ‘socialists’ or ‘communists’. Even Russia’s Bolsheviks and Mensheviks were factions of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party. A clearer distinction emerged from the rubble of war, in the run-up to which far too many social democrats across Europe jettisoned their internationalism and switched to what was defined at the time as ‘social patriotism’.

Socialist Rosa Luxemburg was murdered a century ago.

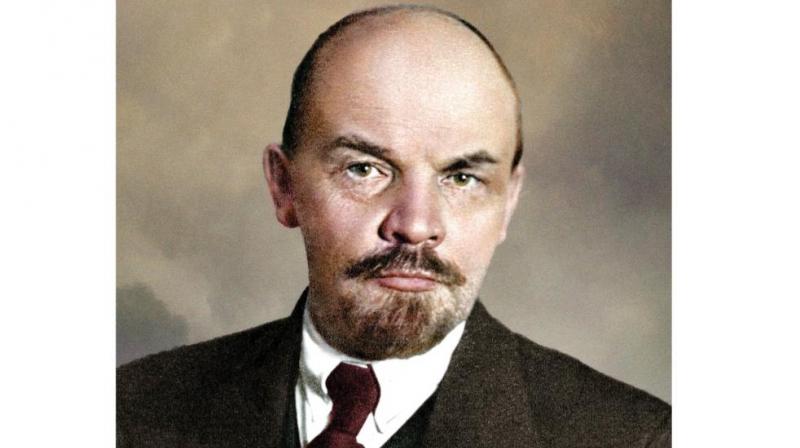

Luxemburg, a Polish Jew who had escaped the tsarist authoritarianism of her native land to embed herself in Prussian politics, was utterly appalled by the attitude of her adopted party. Notwithstanding the considerable differences between them, the Russian exile Vladimir Lenin shared her rage. The ‘revolutionary defeatism’ he espoused wasn’t all that far removed from Luxemburg’s idea of converting the imperialist clash into a civil war.

Her relentless agitation against the war meant that she was imprisoned for much of its duration. It was in her prison cell that she reflected on the two Russian revolutions of 1917, critically empathising with the Bolshevik takeover, decrying its authoritarian, anti-democratic tendencies, but grudgingly acknowledging that Lenin and his comrades had little choice at the time, in the absence of revolutionary outbreaks elsewhere on the continent.

Germany was transformed on the eve of the November 1918 armistice, largely through direct action by soldiers, sailors and workers.

Luxemburg eventually walked out of prison, shortly after Liebknecht, and at the end of the year their Spartacus League faction of the SPD was transformed into the Communist Party of Germany. At the founding convention, Luxemburg reiterated her stance that a takeover of power was inconceivable without majority popular support. But when an insurrection broke out in Berlin in the first week of the new year, she could not bring herself to oppose it despite her theoretical objections.

The troops poured in under the chancellorship of her former pupil Friedrich Ebert, and the premature uprising was crushed. Luxemburg saw the defeat as a salutary lesson, but was denied the opportunity to theoretically or practically dwell on its consequences.

In her time, Luxemburg was both adored and detested as an independent-minded thinker and as a highly effective agitator who cut a frail figure but invariably moved audiences with the power of her words. Marx’s biographer Franz Mehring described her as the leading Marxist theoretician of her times, above not only Lenin but also Eduard Bernstein and Karl Kautsky, who were at one time considered the inheritors of the Marx-Engels mantle.

Luxemburg, in fact, was willing even to take on Friedrich Engels himself at one of his last appearances at a European socialist conference shortly before he died in 1895. Her early pamphlet Social Reform or Revolution powerfully laid out the case for the latter, and capitalism’s incapacity for sufficient reform was a lifelong theme, alongside compelling denunciations of imperialism.

Her disdain for nationalism, including its Jewish incarnation, led her to challenge Lenin’s eventual insistence on national self-determination.

It is unfortunate that Margarethe von Trotta’s otherwise excellent 1986 biopic completely glosses over Luxemburg’s enlightening and in many ways prescient response to the Bolshevik triumph of 1917 and her earlier interactions with Lenin.

How she might have influenced the trajectory of European socialism is open to conjecture, but it’s hard to disagree with Leon Trotsky’s conclusion, in a eulogy delivered within days of the murders, that Marxism “had entered into her very blood”.

By arrangement with Dawn