#MeToo version 2.0 starts now

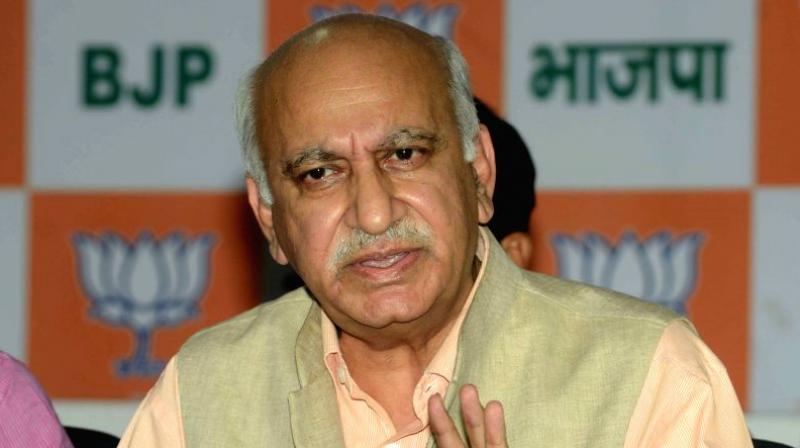

The hearing on the criminal case against journalist Priya Ramani by former editor and BJP MP MJ Akbar starts today.

First the news.

The hearing on the criminal case against journalist Priya Ramani by former editor and BJP MP MJ Akbar starts today. Yesterday, Modi government's junior foreign minister Akbar quit facing sexual harassment allegations from 36 women so far. However, it is pertinent to note here that the PMO had first rejected Minister Maneka Gandhi's proposal to constitute an inquiry committee of four retired SC/HC judges against MJ Akbar and other high profile persons against whom charges were brought, and the rationale given was that it is an urban elite issue and will not harm BJP politically. And, Akbar still remains Rajya Sabha MP from BJP.

Impact ahead.

After Akbar tendered his resignation, Priya Ramani tweeted that "as women we feel vindicated" and she is looking forward to the day when she gets justice in court. There are enough indications that the defamation case will fall flat as there will be now a flood of accusations against MJ Akbar, and rightly so. More than 20 former employees of Akbar's Asian Age have asked the court hearing the defamation case filed by Akbar against journalist Priya Ramani, to consider their testimony about the "culture of casual misogyny, entitlement and sexual predation that he engendered and presided over" at the organisation.

This is now not Priya's battle alone. And in court and outside, the next phase of the battle starts today.

And this will only grow stronger with every passing day with biggies like Alok Nath, Subhas Ghai, Suhel Seth, Sajid Khan and many others caught up in the web. Several organizations like Phantom and AIB have been dissolved or lost projects. The movement surely is growing and is likely to lead to many recounting of experiences from media and other sectors which are known for exploitation of women: entertainment, advertising, hospitality, legal and some corporate houses.

The other aspect is many men are openly coming in support of this rising tide. Author Rashid Kidwai and India Today Online Editor Kamlesh Singh, both former Asian Age employees, who have come out openly to support their former colleagues and the cause. Priya's journalist husband Samar Harlankar has written a powerful piece saluting his wife.

What will be important to note is the impact this rising tide has in the hinterland, in regional media, in small towns of India. Such sexually aggressive behaviour by men — along with the lewd comments, the demand for sex, their bodies rubbed against the female body — are part of the everyday experience of women on India’s streets, public transport and homes. For many men, violence against women — of which sexual harassment is just a small part — works much as drugs do for addicts: it offers at least the illusion of empowerment where none exists, fixing feelings of rage and impotence when they have no claim to a dignified life in a jobless economy. And for some men, sadly enough, this is the proof of their power and entitlement.

Failed Context of Women Security:

Gender mainstreaming has been attempted across decades through government policies and by civil society. There has been a policy movement from welfare of women to all-round development to empowerment to positive discrimination ensuring inclusivity in terms of women's access to health, education and participation. It is in the domain of participation that needs safety, security and equality. In spite of these attempts, female literacy in India is at 64.6% far lower than global average of 79.7%. Only 31% of women in productive age is in some sort of employment, with a large number of them low paid and even unpaid.

The current wave of feminism globally is centred on technology. Women are using digital tools as a means of expression. The emergence of an individual voice, and a means to carry that voice to the people through the social media and the Internet, is perhaps the single most important factor, which has given this movement the traction it has gained.

Also, this movement is built after several failures of the society and the State to protect the women. It is also built on global movements seeking equality in suffrage, education and economic opportunity. It is a call from feminists across the world to value the contribution of people who have not been given access to the corridors of power and to recognise basic tenets of equal opportunity in all spheres of life.

The Law, Its Limitations & Its Strengths:

The Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013, allows for complaints to be made within 30 days of the incident, and in case of delay within an additional 30 days. If complaints are made within time, the Act is a potent tool in the hands of victims to take strict action against the perpetrator of such crimes.

Section 468 of the Code of Criminal Procedure provides for a period of limitation with respect to certain offences wherein the punishment prescribed is imprisonment under three years. With respect to offences where the punishment prescribed is over three years, no limitation is prescribed for filing of complaints. Condonation of delay is also provided in cases where the court deems fit in the circumstances and finds that the delay was bona fide and not due to latches. In light of the law laid down above, the remedy for victims is to approach the courts and the police and make complaints. Perpetrators will have to face trial. They are presumed innocent until proven guilty. The burden of proof is on the perpetrator, not the victim.

#MeToo Version 2.0 Ahead:

#MeToo is a movement about equality, against misplaced masculinity and for a dignified work-place. It does not question consensual relations, it should not be used for settling personal scores through lies and it should not be seen as a passing fad. #MeToo is about dismantling hierarchies of power that have existed for centuries, in our governments, court systems, corporate offices, family homes, and cultural institutions. Because power has always been consolidated into the hands of men, men have also been the ones framing laws and rules and social norms around their experiences. As a result, most social norms, and our processes for re-evaluating them, have excluded the voices, perspectives, and experiences of women. What we are now experiencing is the collective outpouring of rage over centuries of institutionalised sexism, which needs to enter the portals of other sectors of the economy and in various geographies of the country. Hence, the movement is as much for gender parity as against abuse of power.

If we are able to redefine the norms around consent and masculinity that are at the core of #MeToo, we will move towards a new world-view in our office and public spaces. We may be then working towards a world where there is no female infanticide, no domestic violence, no eve-teasing on the streets, no barriers to girls’ education, no gender discrimination in homes and workplaces.

One thing from the Akbar episode is clear. If those affected stand in unison and if media is sensitive towards real issues of people, an arrogant government also yields. Can the media take it ahead with all causes they should stand by? Can the media moguls now take care to ensure better working environment for women? Will the corporate, the legal, the hotel and entertainment worlds take lessons from this? These are other dens of unsafe work environments for women.