We need to bring civility, make campaigns cleaner

Second, each party needs to concentrate on ideas and performance, against the promises made.

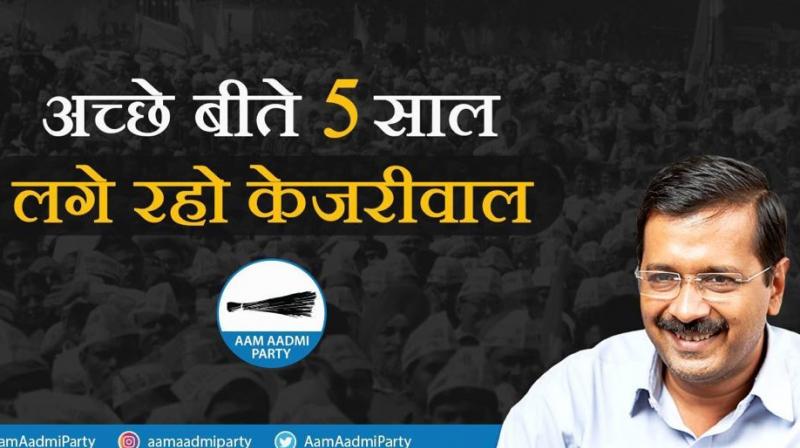

The “why” and “how” of the verdict in the recent Delhi elections are being debated endlessly by activists and intellectuals across India. Since poll outcomes depend on many factors, including the performance of the government in power, anticipation and management of perceptions, the credibility and antecedents of candidates fielded, the manifestoes of the competing parties and the ability of leaders to work for better conversion of votes into seats and anti-incumbency sentiments, any result can be justified with permutations and combinations of such factors. Electoral rhetoric often adds to the drama.

One may argue whether the overall quality of discourse before polls has improved over the years, the language used has often reached gutter levels, or whether relevant issues are framed for an informed debate or not, but there is little doubt that political pronouncements, promises and even gimmicks follow a predictable pattern and are thus less stimulating to discerning voters. Is it feasible to develop a framework in make the process more informed, nuanced and challenging? Here are a few ideas.

First, to enable a voter to exercise his/her option conscientiously, the leaders of political parties must first explain clearly the respective roles of the Centre and state governments, pursuant to the demarcation of powers in the Union, State and Concurrent lists of the Constitution, in maintaining peace and in promoting development activities in that specific constituency. In an Assembly election, for example, the leaders should explain how, within the powers vested with the state government, health and educational standards have improved, how communal harmony is fostered, how activities like road building, construction, distribution of piped water supply, creation of irrigation facilities and completion of other public works have been undertaken, how local self-governments like panchayats and municipalities have been empowered, how employment opportunities have been created in that constituency, and the like.

The discourse for parliamentary elections should, for instance, focus on how the Centre succeeded in defending the borders, foiling terrorism, improving relationships with neighbouring countries, handling the contentious citizenship issue and managing the economy. Equally critical is how the Centre, through devolution of resources to states, has enabled them to move towards the Millennium Development Goals. In the case of a specific constituency, one can focus on Central institutions set up, how many miles of national highways have been added, how Central funding for various shemes has been utilised, how railway or communications tworks have been expanded,and suchlike. For both Assembly and Lok Sabha polls, the Oposition should try to counter these declarations, rebut allegations made with relevant facts, and explain what they would do, if elected to power.

Second, each party needs to concentrate on ideas and performance, against the promises made. Attacking individuals, often via exaggerated allegations of corruption, may attract headlines and even dent a candidate’s winning potential, but may not be a good poll strategy. If an individual has indulged in corrupt activities, the best recourse is to take the matter to the courts. On the other hand, deliberations on issues and ideas may be more effective.

Third, it is important to ensure that the two other organs of the State — the legislature and the judiciary — are not mindlessly undermined. It has been a trend to castigate Parliament or the higher judiciary if the laws passed through due process or reasoned judgments delivered by the courts don’t suit the requirements of the Opposition parties. Admittedly, all of us are entitled to criticise the wisdom of Parliament or of the high courts and the Supreme Court. But serious and orchestrated attempts to malign these institutions, doubting the motives of individuals, may not be in the highest public interest. If a law is enacted, it is binding on all unless invalidated by the highest court. In Parliament, since voting takes place on party lines, the outcome is generally predictable. But in the courts, each judge in a bench exercises his/her discretion. Therefore, undermining the decisions of a Constitution Bench or seeking, through the media, to indirectly influence a decision, smacks of low self-esteem.

Fourth, while using expressions of dissatisfaction, even dismay, shouldn’t some restraint be exercised in respect of the chief minister for Assembly polls and the Prime Minister for parliamentary elections? In election time, some levity is allowed and is even enjoyed by people, but any disdainful reference, especially of a personal nature, directly at a CM or at the PM, who has to maintain an international image, could perhaps be avoided to the extent possible. Civility does not hurt.

Finally, can there be a political consensus about some strict “no-go” areas during campaigning — such as any attempt that may encourage divisiveness within the body politic? India’s federal spirit thrives on the strength of individual states and their symbiotic relationship with the Centre. In the early days after independence, Jawaharlal Nehru’s public meetings used to be lessons in adult education. He used to explain the value of freedom and democracy, the need for inter-religious amity, the necessity of getting over the shackles of caste and superstitions, and the strengthening of the Centre-state relationship, in order to build an India, aptly visualised by Rabindranath Tagore as “Where the mind is without fear, and the head is held high…” Even then his government had been criticised as dictatorial, fascistic and promoting “licence-permit raj”. As a matter of fact, governments in the past seven decades were relentlessly lampooned by the Opposition parties and public intellectuals. Way back in 1933, the Oxford Union debated and carried the motion “That this House will in no circumstances fight for its King and Country”, much to the chagrin of many, including Winston Churchill.

Therefore, democratic dissent must be lived through, even if allegations may sound exaggerated, preposterous and even “manufactured”, and requires to be politically negotiated. That by itself does not constitute an adequate reason for political discourse to remain pitched to a mediocre and predictable level, peppered occasionally by hate speech and muscle-flexing. While the average quality of debate might not have deteriorated over the decades, there are obviously no apparent signs of improvement either. Does it behove a maturing democracy? The Supreme Court’s recent direction that would discourage the fielding of dubious candidates may turn out to be a game-changer.