Will Modi live up to his ‘sabka vishwas’ vision?

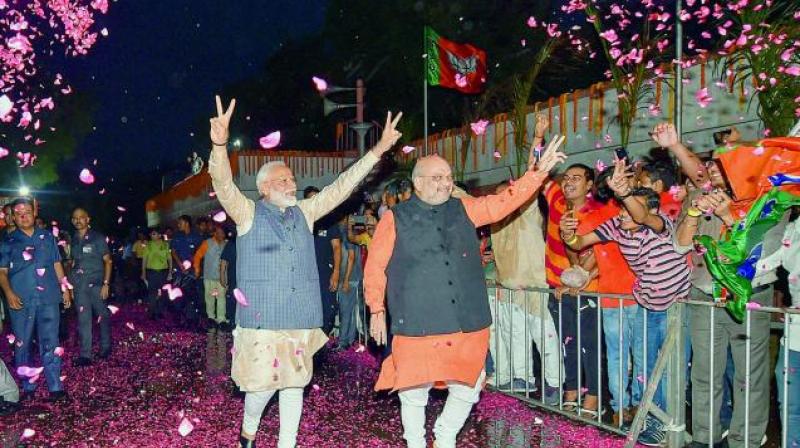

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s speech at the meeting of members of Parliament from the BJP and its alliance partners on Saturday, May 25, was an extremely evocative speech and has the capacity to alter the flow of Indian politics in the majoritarian direction. The only scepticism is if he, more than anyone else, believes or follows even a word of what he said.

But before one turns judgmental, it must be noted that Mr Modi should be applauded for displaying boldness in his address. At a macro level he made possibly the most reassuring declaration he has ever made unambiguously —his government would not discriminate between those who had voted for the BJP and its allies, and those who did not. He, in fact, said it was natural for the elected MPs of his party, especially after such a resounding victory, to thump their chests and look down upon those easily identifiable as those who did not vote for them. “This”, Mr Modi said, is a “liberty which elected representatives cannot take”. They must work for all irrespective of their political convictions, Mr Modi concluded.

The first test of how true he will be to his words in his second tenure will be when he draws up his council of ministers. Will he, for one, include Maneka Gandhi in his team despite her warning to Muslims that if they did not vote for her, they could not expect her to help them if she won? She had also delivered another speech which goes against the democratic spirit and what Mr Modi said: “When the election comes and this booth throws up 100 votes or 50 votes, and then you come to me for work, we will see.”

Ms Gandhi is the not the only one who has spoken against any particular community or those who are known for views against the BJP or the government. Instead of trying to win them over, as Mr Modi prescribed, many ministers and parliamentarians advised critics to leave for Pakistan or elsewhere. Would such leaders, many of who were part of the council of ministers till the end, be left out of Mr Modi’s new team or will he again accommodate them to placate the core electoral constituency?

Ms Gandhi’s first threat was directed at a community, but the second was far more worrying. The Election Commission of India and the government retained the systemic possibility of identifying people, with use of intelligent guesswork based on micro-level profile of voters, who did not vote for candidates of a particular party. In the paper ballot era, voters were guaranteed that their choice would remain secret because ballot papers from various booths were mixed up and churned in big drums before counting.

After the introduction of EVMs in every constituency from 2004, voting breakup in every booth — an average of around 1,000 voters — is available publicly in the Form 20. Candidates and their booth agents, especially of parties which have a cadre and are politically connected after the polls are over, can make a fair guess in identifying the people who did not vote for them. If Mr Modi is true to his words, he must roll back the government’s decision of not going in for the totaliser machines before the EVMs were tabulated. These totaliser machines can be connected with up to 14 EVM machines and the votes can be electronically mixed, ensuring the secrecy of ballot and will structurally prevent government welfare schemes bypassing those who did not vote for it.

While at the macro level Mr Modi pledged that he would now go on to secure “sabka vishwas”, or everyone’s trust, at the micro level the Prime Minister advised habitual motormouths to control their desire for publicity. But advice is not enough. If any MP or leader chooses to be indiscreet and vitiates the atmosphere, Mr Modi and his party must immediately initiate action and mete out punishment which is visible. He cannot continue remaining silent as was his wont during the first term.

For instance, in 2014, Niranjan Jyoti was not sacked from the ministry. Instead, Mr Modi mounted a defence in the Lok Sabha: “She is a new minister, we know her social background, she is from a village...” Vice-President M. Venkaiah Naidu, then parliamentary affairs minister, provided further defence and mentioned her “social background” as a factor. Certainly, no action was taken against her because she had significant support among Nishads. Will Mr Modi be now more reassured and bolder to take action against offending ministers or legislators?

Mr Modi made two other promises which, if fulfilled, would make his government much more representative and inclusive.

Unlike before, when he was dismissive of coalition partners arguing they were driven by the glue of “winnability”, implying that the BJP could sideline them if it did not require additional numbers, he stressed on the importance of coalitions. He assured the nation that he would factor in regional aspirations. But it was his unbending attitude on the issue which caused friction, leading to the eventual parting, with N. Chandrababu Naidu of the Telugu Desam Party.

These words are easy to say, difficult to live up to. For starters, the BJP’s hegemony within the NDA is greater than in 2014 and it would require a fundamental change in his attitude towards them. Take, for instance, his advice to those aspiring to become ministers. While there is no denying that the ministry is the Prime Minister’s prerogative, his words indicate his comfort with the power this mandate has vested on him. Would the council of ministers be more consultative and ministers be given more liberty to initiate policy? Or would the centralised style of governance, that was a feature of the first tenure, be the norm even now? There will be political problems in continued accommodation of allies as there are sharp divergences between the BJP and its partners on several sensitive national issues, including handling of the situation in Kashmir. More than anyone else, Mr Modi will face the sternest test in following his own words.

The writer is the author of Narendra Modi: The Man, the Times and Sikhs: The Untold Agony of 1984