K.C. Singh | China’s Xi: Divide or intimidate & conquer

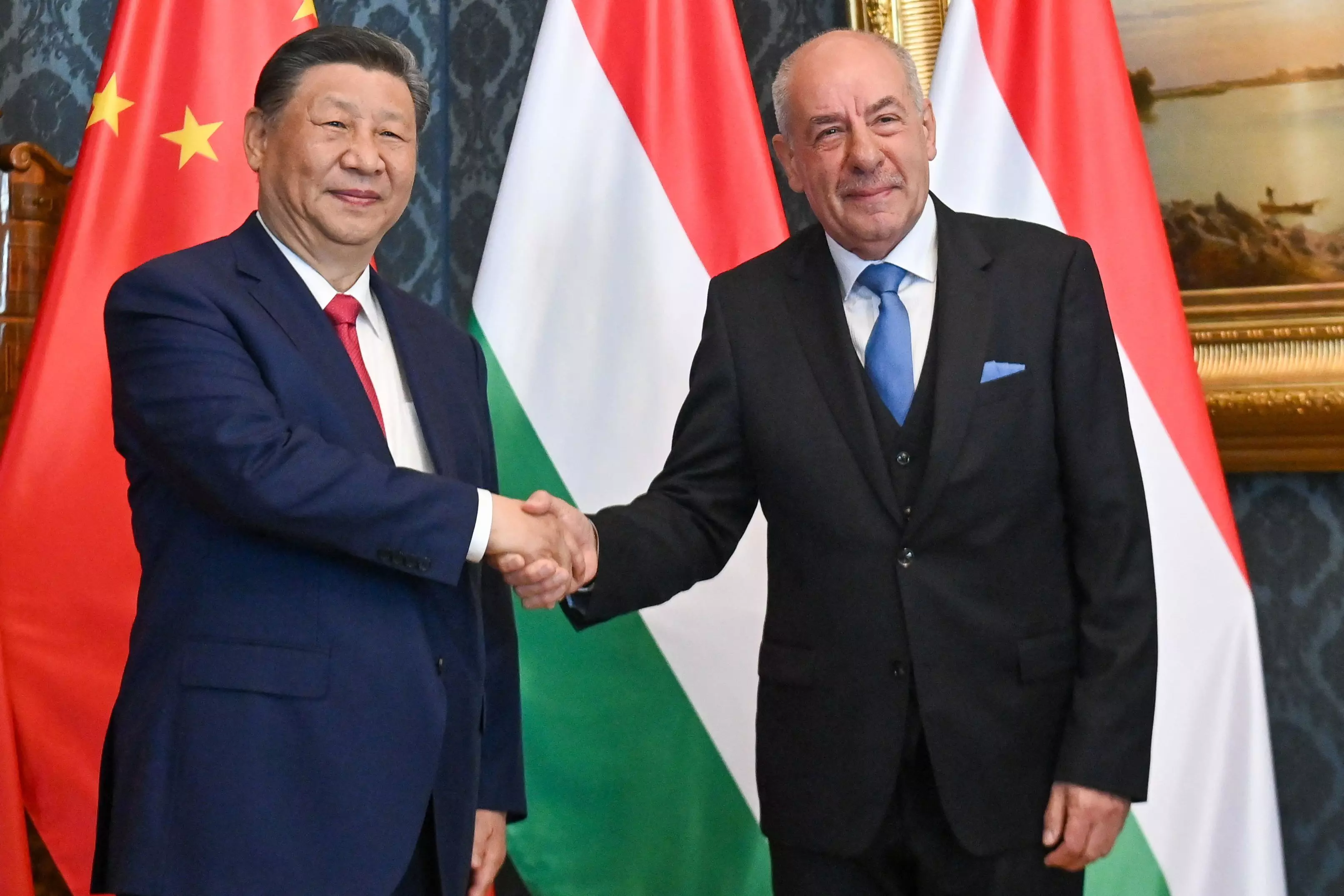

China’s President Xi Jinping has at last begun his structured foreign travel after his stay-at-home posture during and after the Covid-19 pandemic. This was partly due to a delayed Covid-19 surge in China as the movement restrictions were lifted, when the rest of the world had crossed peak infections. This week he began a six-day swirl through Europe, starting with France, and then mostly China-friendly nations such as Hungary. Serbia was included as it marked 25 years since the Nato forces mistakenly bombed the Chinese diplomatic premises in Belgrade in the late 1990s.

This happens when the Chinese economic slowdown is now broadly accepted. The International Monetary Fund in its February 2024 report observed that economic growth this year shall be 4.6 per cent, down from 5.2 per cent the previous year.

Even more worrisome for China should be their assessment of its drop to 3.4 per cent by 2028. This appears to be due to a combined effect of demographic shrinkage, Western sanctions on cutting-edge technology and restricted Western market access. President Xi’s distrust of the private sector and entrepreneurship probably makes a turnaround difficult.

One obvious result is that talk about China catching up with the United States or even overtaking it has mellowed. In fact, it is generally accepted that even though the American economy is slowing, but at a lesser pace than China’s, their gap is, if anything, widening. Analysts are speculating that when a rising power, desperate to catch up with the dominant hegemon, starts stalling, one of two things can happen. Its leadership may alter its aggressive behaviour towards the world, especially the neighbours, opting instead for diplomacy. Alternatively, it may get desperate and decide to use force to achieve its territorial objectives, realising its power-differential vis a vis its rivals will diminish over time.

Obviously, no sudden change in Chinese strategic posture can be expected.

China would not like its rivals to benefit from its perceived weakness. Its recent actions need to be viewed from this perspective. Before setting forth for Europe, China unveiled its third aircraft-carrier, the Fujian. A 80,000-tonne vessel with electromagnetic catapults, on a rough calculation, would enable it to carry 70-80 aircraft. China is planning to have six such vessels by 2035. This still leaves the combined naval power of the US and Japan way ahead. The US Navy, with carriers of the Nimitz and Ford class, has more experience, better aircraft and greater firepower. The Japanese, with considerable experience of using aircraft-carriers since the Second World War, have opted for flat-top vessels with the possibility of being used as carriers for vertical take-off and landing F-35s.

Interestingly, the maiden voyage of the Fujian coincided with the May 8 Balikatan joint military exercise of the US and the Philippines. The Chinese have been muscling the Filipinos out of the Scarborough Shoal naval area. The Philippines had in 2016 got an award, under the UN Convention on the Laws of the Seas (UNCLOS), from the Permanent Court of Arbitration declaring the Chinese 9-dash line as illegal. China has nevertheless continued to thwart attempts by the Philippines to assert its sovereignty in that zone.

Even the territorial dispute between India and China has not seen China relenting yet. In fact, China has been increasing settlements all along the India-China Line of Actual Control (LAC). China also provocatively issued maps with habitations in India’s Arunachal Pradesh shown with Chinese names. Meanwhile, military-level talks have repeatedly faced a stalemate with China unwilling to withdraw forces from the Depsang Plains and Demchok. It is likely that China did not wish to hand the Narendra Modi government a “win” on the eve of crucial Lok Sabha elections. This assumption aligns with China now naming its next ambassador to India, after a gap of a year and a half. At the very least, China may be preparing to use the diplomatic route for testing the next Indian government’s willingness to engage. The problem is that China wants access to the Indian market to continue, if not increase, while it stalls on territorial issues. India has repeatedly asserted that normalcy requires the post-Galwan territorial intrusions to be addressed.

President Xi’s European sojourn is similarly planned to test and exploit the fissures, on the approach to China, within the European Union and between them and the United States. The visit comes after the China visit by German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, which seemed to display European differences. Further demonstrating that dissension has been Mr Scholz’s unwillingness to join French President Emmanuel Macron in a joint meeting with President Xi. There are differences in the approach of France and Germany to taxing European imports of Chinese electric vehicles. While the Germans fear Chinese countermeasures against their

automobile exports to China, the French want to protect their own manufacturers of smaller cars.

The Sino-European theatre is being enacted against the background of two other events. One is the November presidential election in the United States. The growing possibility of the re-election of Donald Trump sends shudders down the European spine. It can mean the degrading of Nato, trade disputes with the US and Russia’s upper hand in ending the war in Ukraine on its own terms. The other factor is the commencement this week of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s next six-year term, with a more united Russia behind him.

Regarding both these developments, China is a factor. While it has not transferred weapons to Russia, for its Ukraine campaign, it has kept Russia financially afloat by buying its oil and gas. It has also made available chips or other high-tech components crucial for the Russian armaments industry. China correctly surmises that a strategically divided and confused Europe is easy prey for its overtures. But China would have to alter its subsidies-based exports to satisfy Europe. It would also have to restore confidence regarding Chinese activities in illegally transferring high technology from European sources.

While these larger forces are shadow boxing, India has been entrapped in an unnecessarily prolonged national election. A gap of almost a week between seven phases, many in the same state, cannot be justified on the grounds of security and expediency alone. No nation, and particularly one which aspires for Great Power status, can sign off from the world for well over a month while its leadership takes the low road to opportunistic and divisive electioneering.