Probal DasGupta | From Maldives & beyond: Why India needs the neighbourhood

In a unique phenomenon, the Maldives periodically chooses between two of the largest contestants on earth in a national election. The individual candidates may go by any other name, but the influencer emerges from among the behemoths: India or China. In successive polls, power has changed hands with such metronomic fidelity that the losing candidate bides his time to turn the tables next time.

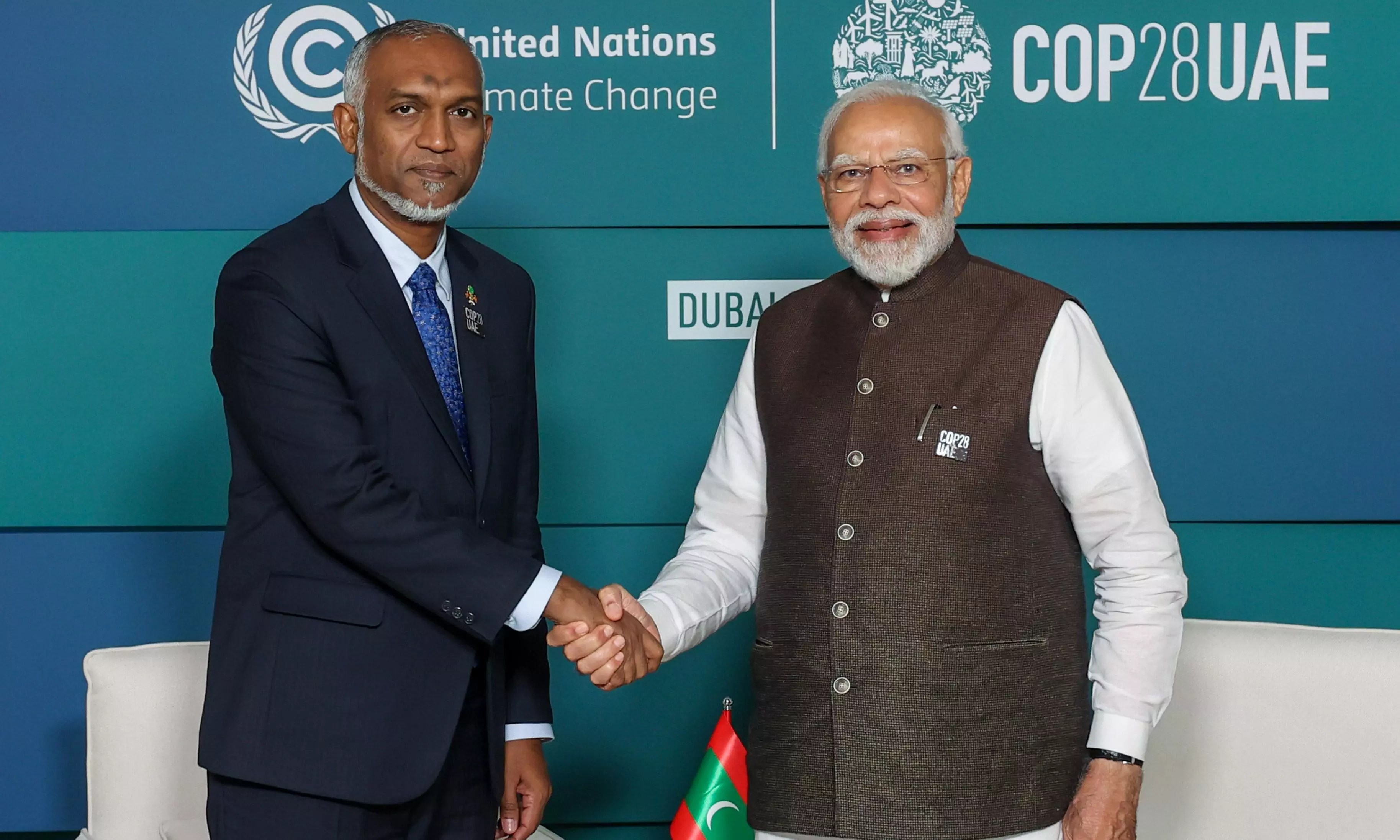

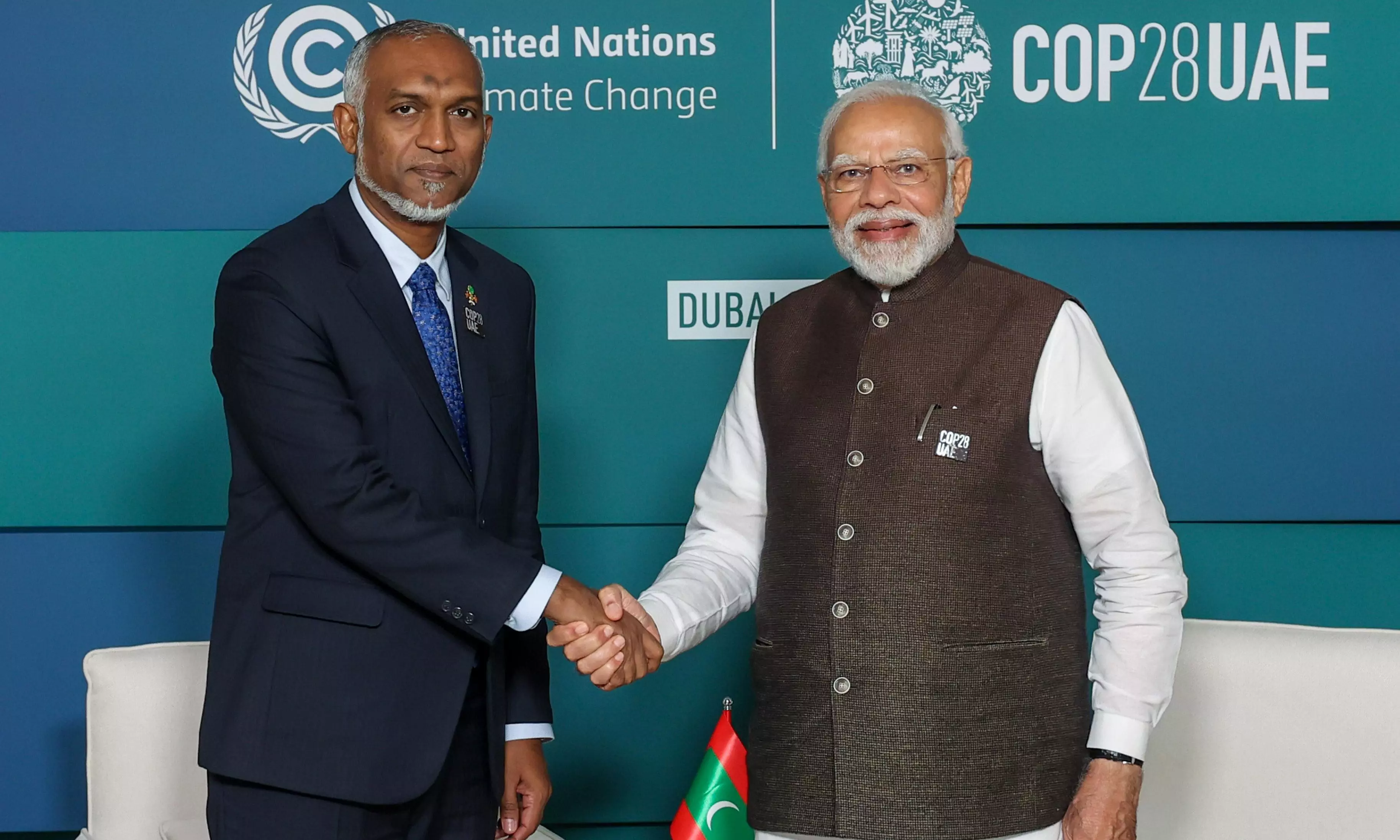

As President Mohammed Muizzu won power in Male, shocking Ibrahim Solih, it was known he would lean towards China. In Mr Muizzu’s early days, with Beijing promising increased infrastructure investments, there was an eagerness to cosy up. This wasn’t unusual as past governments had sided with either of the two powers. But this time, a fine balance was sacrificed in favour of brazenness and antipathy towards an old friend. A trio of deputy ministers threw the gauntlet by ridiculing India’s Prime Minister in an unacceptable manner, rousing anti-India sentiments. The improper comments upset Indians, whose anger virtually scorched the digital space. The Maldives government acted in time and suspended the deputy ministers, but the damage was done. That junior ministers could actually whip up a frenzy and had the agency to drive a wedge in the India-Maldives equation was worrisome. Conversely, it also meant any traveling lowball could catch India’s heels.

Does a collective national outburst over any comments, even excessive ones, make India too predictable? Does it hurt India’s journey to becoming a bigger force in the region?

The rivalry in the region between India and China has turned into a surrogate one. The scrimmage in the Himalayas is likely to be of contained tactical importance, since neither can make headway in the mountains. However, when dimensions of conflict expand to include the oceans and the nations that dot them, it gives rise to the real risk of a Chinese “string of pearls” around India through satellite states and naval bases. That is where emotional outbursts on every issue can become self-goals for India.

The Chinese positions have stayed the course. Beijing’s thinking on the Maldives began even before the rise of Xi Jinping. Until 2002, there was no worthwhile trade, but in the next decade, trade increased from $3 million to over $60 million. In the next decade, trade volumes crossed $500 million. China has been working hard in these countries to build infrastructure which it can later leverage.

The extent of China’s footprint in the country can be gauged by the fact that China’s Exim Bank funded the construction of the Sinamale bridge connection to Male and modernisation of Velana International Airport in Male alongside investments in agriculture.

Lt. Gen. Rakesh Sharma of the Vivekananda International Foundation believes that, unlike China’s deep pockets for investment, India is known to build relationships through people and essential services like medical tourism and education. Though he asserts the initial anguish against the remarks of the Maldivian ministers was normal, he cautions about going on an overdrive. A senior diplomat was heard on television sermonising our neighbours not to cross “red lines”. “The strength of diplomacy is to deal with inimical governments,” counters Lt. Gen. Sharma. In support, he notes recent examples of India’s dealings with the Taliban and earlier with Pakistani governments where back channels were deftly used.

There is an impression in India that any hostile issue can be whipped up into a public interest phenomenon by crowding out unfavourable views using sheer numbers on social media. But those jumping on this bandwagon have little or no understanding of how international affairs and strategic choices work. The theatrics of tour and travel operators and celebrities falling over themselves by cancelling tours to prove loyalty, when the government had refrained from indulging in mudslinging, was a case of unsought genuflection by those whose decisions were skewed by an outburst of emotions.

Take the case of a tourism outfit promising to transform Lakshadweep into the Maldives. Any comparison of infrastructure and potential between the Maldives and Lakshadweep is untenable. To claim that Lakshadweep, with its vulnerable ecosystem and just 36 islands, can be transformed into a tourist paradise, outstripping the Maldives with over 1,100 islands (of which 187 are inhabited) is outrageous and fanciful.

According to Maldives’ tourism ministry, the Chinese didn’t comprise the top 10 list of tourists in January 2023 while Indian tourists were the second highest contributor.

However, by the end of 2023, the surge of Chinese tourists catapulted it to the third spot. Given the rapid change in tourist demographics, Mr Muizzu’s plea to China for tourists will increase the Chinese footprint in the islands and could challenge India’s influence in future.

In the Covid-19 pandemic, the Maldives was the only nation accessible to Indians without a visa. Previously, Sri Lanka went through a cycle of pro-China and pro-India periods. India’s relations with Nepal hit a roller- coaster. After his China visit, Mr Muizzu spat out: “We may be small, but that doesn’t give you the licence to bully us.”

Mr Muizzu knows his cards well, having scrapped the India-Maldives hydrography agreement. This makes way for a Chinese research ship to dock in Male in February, despite India’s concerns over Chinese vessels in the Indian Ocean. India managed to turn things around in Sri Lanka earlier. Given its location, size and lack of democracy, Maldives is a more vulnerable state. Lt. Gen. Sharma believes India needs to work with its neighbours if it aspires to leadership of the Global South. Given Beijing’s malevolent machinations, a powerful India that treats its neighbours as equals stands to gain much greater acceptability. Like accountability in a war stops at the general’s door, the buck in political tussles must stop at the gates of diplomacy.