Shikha Mukerjee | Politics of deep divides, prejudice & reservation

The accusations of prejudice, amounting to negative discrimination against a Dalit candidate on the criteria used for the appointment of the pro-tem Speaker of the 18th Lok Sabha, a job that ends with the swearing-in the 543 newly-elected representatives, expose the deep divide not only within the political class, but about social prejudice, justice and a dynamic interpretation of equality.

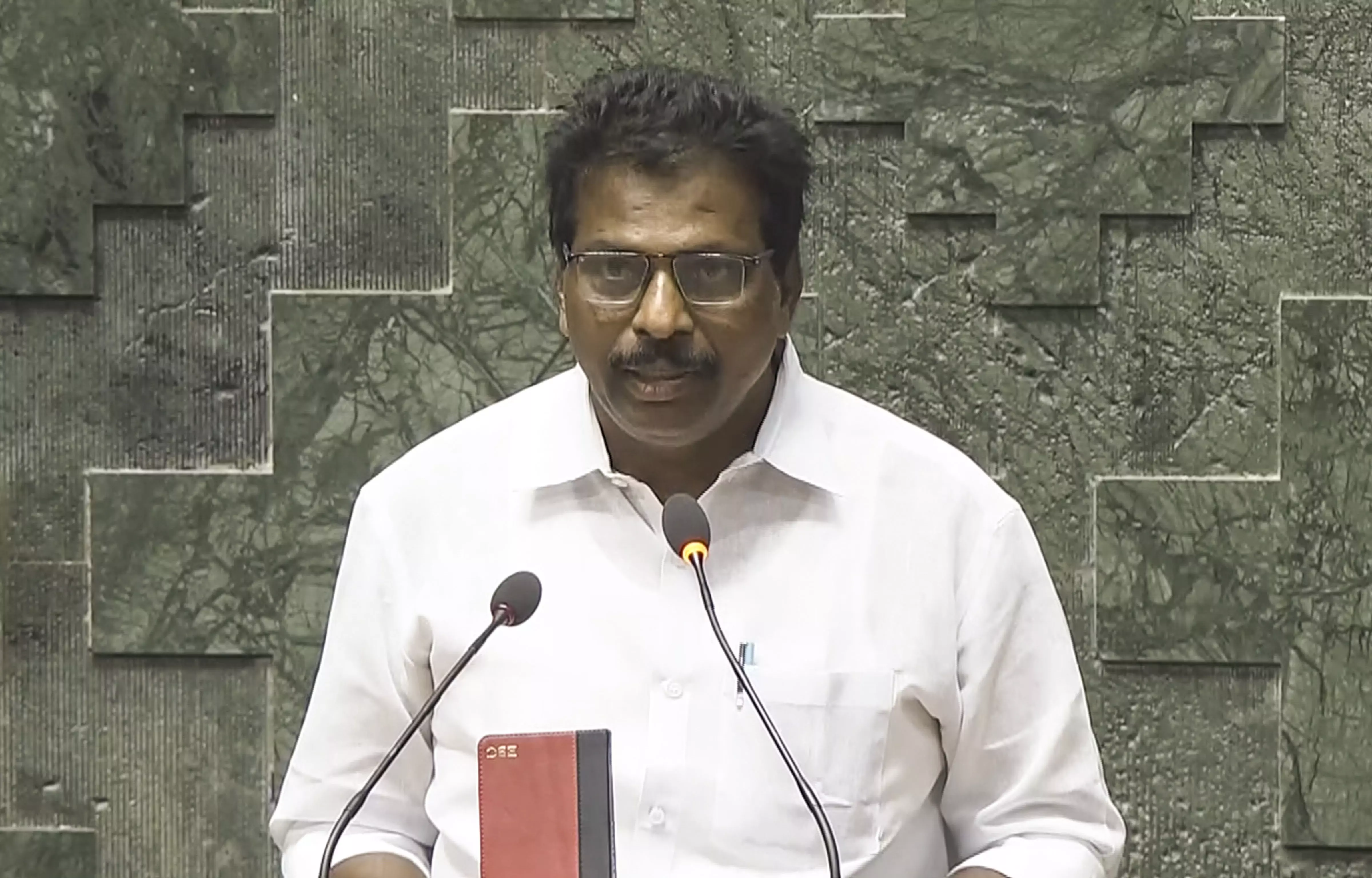

The Congress, probably in anticipation of a fight, declared that its eight-time MP, Kodikunnil Suresh from Kerala, who is incidentally a Dalit, ought to be the pro-tem Speaker, because that was what convention required. The BJP-dominated House, despite its minority status in terms of seats, insisted that its candidate, the upper caste Bhartruhari Mahatab from Odisha, best fulfilled the criteria of seniority that is used for appointment of the pro-tem Speaker, as per the Westminster model.

The multiplicity of ways in which a person can be identified creates the spaces for divergences and its consequent confrontations to proliferate, instead of celebration of the uniquely diverse population of India. This is as true for the appointment of the pro-tem Speaker as it is for the permanent state of collision over reservation for the backward classes, the socially and educationally underprivileged, the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes as well as the Economically Weaker Section, a category that was confirmed in 2019 through the 124th amendment to the Constitution.

Political and ideological differences on how the backward classes and the EWS ought to be identified and categorised, whether it should be an inclusive or exclusive identification, contributes to the divisions and parallel perspectives. No political party can afford to declare that it stands against the principle of reservation, which is India’s solution through its own model of affirmative action on the millennia old problem of social discrimination based on the caste system, its endemic poverty, inequality and injustice. To do so would be politically suicidal because after 18 elections for choosing representatives to the Lok Sabha and more than 18 elections in almost every state for choosing legislators, the discriminated are fully aware of the power they possess and have learnt to exert as voters and as vote banks.

Ideologically, there are parallel perspectives on who can be identified as deserving of the benefits of reservation and how that can be accommodated in a structure with a 50 per cent cap put on reservation as a principle by the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the Constitution. After the cancellation of reservation for Muslims based on the identification of sections of the community as belonging to the backward classes by the BJP’s Basavaraj Bommai government in Karnataka in 2023 and the party’s 2024 Lok Sabha election campaign spearheaded by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who declared that reservation for Muslims was a Muslim League agenda that aimed to overturn the basic structure of the Constitution, there is no doubt that a line has been drawn. The purpose of the line is to exclude a community.

On the other side of the line are various political parties, most of whom are partners of the Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance and other regional parties that are now with the National Democratic Alliance headed by the BJP, like the Telegu Desam Party in Andhra Pradesh and the Janata Dal (United) in Bihar. There are differences within these parties on what percentile of Muslims in states like Kerala, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Bihar, West Bengal and Tamil Nadu will be included as beneficiaries of affirmative action through reservation, but the in-principle adoption of the right to reservation underlies the various legislation passed, regardless of the number of litigations and judgments by the high courts and the Supreme Court.

The 2024 Lok Sabha election campaign revealed that one other line has been drawn, creating a divide within the political establishment between parties that are for and parties against the inviolability of the 50 per cent cap put on reservations for the backward classes and the economically weaker sections. Unsurprisingly, the BJP, as Mr Modi campaigned, is against any change to the 50 per cent cap. Equally predictably, the Congress and the INDIA parties are for a change of the 50 per cent cap if it is justified.

The confrontation between defending the status quo, which is a conservative position, and the liberal-progressive perspective that change based on data for which a Caste and Social and Economic Census of the population is imperative, is a deep divide. It reflects an ideological conflict on democracy and the interpretation of the fundamental principles of equality and justice.

It is not enough for Prime Minister Modi to declare that he will defend the Constitution of Dr B.R. Ambedkar against those who want to overturn it. Nor it is enough for the Congress, JD(U), TDP, DMK, the Trinamul Congress, Rashtriya Janata Dal, Samajwadi Party and the Left parties to insist that a caste census based overhaul of the principle of reservation and the inclusion of communities excluded by the original version of the reservation principle is necessary for democracy, equality and justice.

There are issues within the principle of reservation that need to be addressed as much by the ruling alliance as by the Opposition or the coalition that believes it is in wait mode to supplant the BJP-led NDA. In Maharashtra, for instance, there is the Maratha reservation demand that no political party in the state opposes, but at the same time, no political party has done the hard work of negotiating how that reservation can be brought about.

A national debate, not a campaign confrontation, is vitally necessary on reservation for the backward classes and EWS for starters. There is no consensus on how going forward, the backward or economically weak is to be measured, because all changes to the principle and the policies that flow from it on reservation-affirmative action have to be worked through for the longest possible term. The piecemeal approach that is reflected in the differences in state-legislated reservations and benefits that is the unfortunate fallout of the ambivalence within the provisions of the Constitution is messy and needlessly divergent. While a “one size show fits all” is neither desirable nor ought it to be advocated, a statement of principles and purposes based on a consensus is overdue in that part of the divide that is liberal-progressive and committed to expanding, strengthening and deepening the fundamentals of democracy. On the conservative side of the divide, a statement of principles and objectives is imperative because within the NDA, a consensus on what constitutes affirmative action is quite impossible.