DC Edit | Delhi's ties with Colombo see promising new turn

It was more than symbolic that Sri Lanka should propose a land bridge to connect with India. At no time since the breakout of the ethnic conflict in the early 1980s have Colombo and New Delhi been near enough like this to lend the belief that the geopolitics of the region have changed somewhat, for it does seem Sri Lanka has had to disengage itself from the Chinese embrace lately.

Having suffered at the hands of the debt trap diplomacy of China and in the aftermath of the serious economic strife that gripped the island last year when the Rajapaksas were forced to unceremoniously exit from power, Sri Lanka may now be looking at a settled future thanks to having learnt some home truths about the cost of friendship with China.

In recognising India’s $4bn helping hand as well as that of the IMF through its $2.9bn rescue package, which would not have come without Washington green flagging it, Sri Lanka is indeed looking to reset ties that might help it settle down to an existence nearer normal as India’s closest southern neighbour.

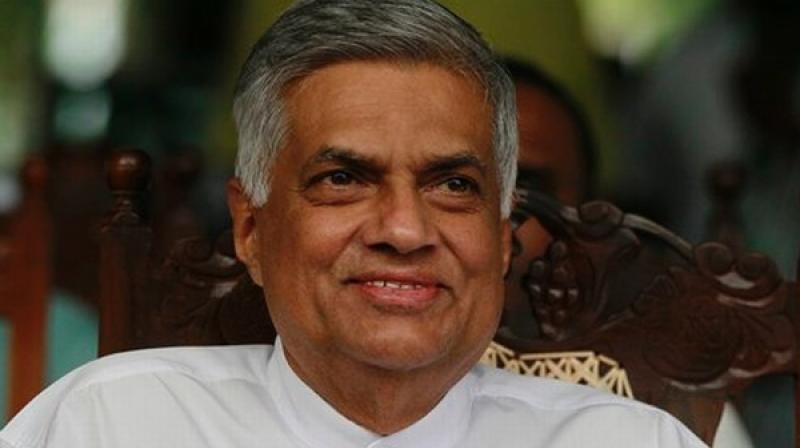

The visit of President Ranil Wickremasinghe last week to New Delhi was not of the customary meet-and-greet variety. It also coincided with the Tamils’ celebration of the bicentenary of their arrival on the island. The land bridge he has proposed may take a long time to materialise, but the very fact that it is being sought now carries a clear message.

A ferry between Nagapattinam, replacing Dhanuskodi that used to be the hub for transfer to the island but was lost to nature’s fury in the 1960s, and Kankesanthurai in Sri Lanka will only be a revival of an old service, and yet an important link in these changing times of Sri Lanka trying to reverse on the big swing to China courtesy Mahinda Rajapaksa. The four pacts that the countries signed last week are also an indicator of a different kind of future in dealing with an equitable partner in promoting trade, industry, infrastructure, and green energy.

The shift in Sri Lanka’s outlook may represent the new normal as the pro-India, pro-West President Ranil is in office. But what New Delhi may find difficult to understand is the reluctance of the island to grant rights under the long-proposed 13th Amendment to their constitution that in theory should give the Tamils of the north and east a more equitable access to the development that has taken place in the southern parts.

Ranil Wickremasinghe himself may be at a loss here as he would be subject to the winds of majoritarian politics that may not permit the granting of full privileges to the Tamils who have long felt the big north-south divide. There has been little progress in attempts to address the Sri Lankan national question, which Wickremasinghe had hoped to before the nation marked 75 years of independence from the British last February. Devolution of power and the Tamils’ right to local self-determination remain unaddressed.

The New Delhi view on Tamil Nadu fishermen being harassed by the Sri Lankan Navy must necessarily be different from how Chennai sees it. There are two sides to the recurring problem of fishing outside India’s territorial waters and it may fester. But the overall Sri Lankan tilt towards India is to be welcomed in view of the island’s strategic location on the maritime routes to the Indo-Pacific. The new era is much more promising from India’s point of view.