Why can't Indians write good memoirs?

A memoir is described as “a collection of memories that an individual writes about moments or events, both public or private, that took place in the subject’s life”. Such memoirs can be that of a lifetime or recollected specifics of a specific event or episode of importance. A biography or autobiography tells the story “of a life”, while a memoir often tells “a story or stories from a life”. David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s founding father, had once said: “Anyone who believes you can’t change history has never tried to write his memoirs.”

One of the best memoirs I have read is Robert F. Kennedy’s insider view of the 13 days of the Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962 when the United States and the then Soviet Union came eyeball to eyeball with their nuclear arms unsheathed. In this unique account, he describes each of the participants during the sometimes hour-to-hour negotiations, with particular attention to the actions and views of his brother, President John F. Kennedy. Do we have any memoirs like this about our recent confrontations with Pakistan at Kargil and 26/11? Sadly, it’s a big No!

It’s ironic that in a country with a long history and an all-pervasive imprint of the government on the everyday lives of people, so little is recorded and hence known about how the State actually functions. Whatever we know about our past is mostly derived from the recordings of foreign travellers like Xuanzang, Faxian, Ibn Battuta or Fernao Nuniz, or by the intellectual curiosity and perspicacity of British administrators, archaeologists and scholars who recreated India’s history for Indians and the world at large. It is not surprising that our histories and mythologies intermingle, and what we like to believe is considered to be our history.

Our public servants are mostly known for their loquaciousness after they demit office but very few actually pen their thoughts. Writing seems to come with difficulty to them, as it requires clarity of mind, an ability to articulate, accuracy and honesty, and above all leaves a trail. What we mostly get from them in seminar rooms all over New Delhi and elsewhere are oral retellings and their vital role or vantage positions when historic events were unfolding. Like all oral history, these get embellished with every retelling.

India has made lifetime course choices and lived through tumultuous times, but very little is known about how choices such as central planning, states reorganisation, the structure of government and even matters like those pertaining to external relations with China and Pakistan and the Cold War were made. We never hear about the processes and the exchanges involved. We ascribe the Five-Year Plans to Jawaharlal Nehru and his interest in Marxism. But there must have been discussions and internal processes, but of these we know very little. What we mostly know about our two major foreign bugbears, China and Pakistan, is more derived from foreign writers and Indian military narrators.

We don’t have political and bureaucratic insider versions to give us a more all-round perspective. Military men are apt to write more often, but more often than not their writings tend to be exculpations or embellishments of their roles in recent events. Thus, we have many such books not only on the 1962, 1965 and 1971 wars but also on more recent conflicts like the Siachen and Kargil wars. But even these steer clear of the less glorious wars in Nagaland, Mizoram, Jammu and Kashmir and Sri Lanka. This is unfortunate because for the best account of the Kargil war we have to rely on a foreigner’s account: Airpower at 18,000’: The Indian Air Force in the Kargil War by Benjamin S. Lambeth of Rand Corporation published as a monograph by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington DC.

I was thus very excited when I began to read Shivshankar Menon’s Choices: Inside the Making of India’s Foreign Policy. He was indeed not just inside India’s foreign policymaking structure for a good part of his distinguished career in the Indian Foreign Service, he was at the heart of it for almost a decade as foreign secretary and then national security adviser. The frisson of excitement didn’t last long for the book is not so much of an account of policymaking, but a set of brilliant and masterful essays on the six major foreign policy issues of his tenure. The origins and even some of the conclusions of these issues are well known. These essays are large sweeps of historical issues from a high perch, but Mr Menon gives away little.

What for instance happened in the Prime Minister’s Office when the Pakistani terrorists struck Mumbai on November 26, 2008 in a daring and brazen attack, which took the lives of 166 people in a few frenzied hours, and then held on to India’s most famous luxury hotel, the Taj Mahal Palace, for three long days as the world watched the helplessness and even ineptness of India’s security forces in hunting down the last holdouts. 26/11 became India’s 9/11.

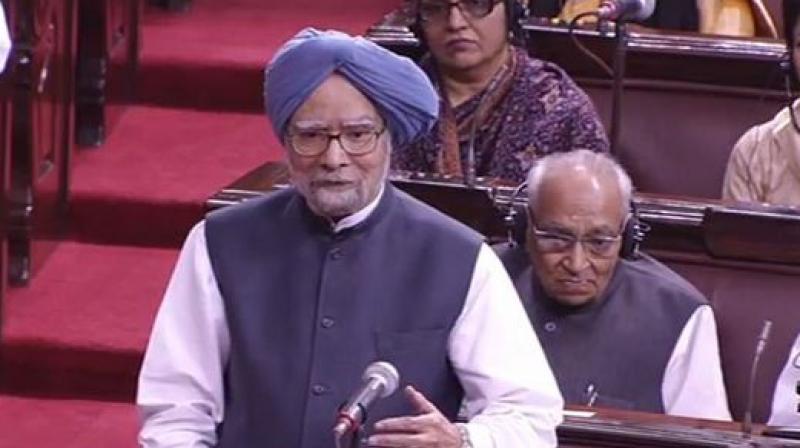

But was this ever discussed in a formal way and what were the military’s views on this? We get no sense of what exactly transpired, maybe out of his sense of loyalty to Manmohan Singh or because of the restrictions placed by the Official Secrets Act of 1923 and the oath of secrecy. Unlike one other who served in the Manmohan Singh PMO, Mr Menon is a thorough gentleman and by nature extremely reticent. Both very admirable qualities and for which he is held in high esteem. Understandably, the other fellow’s books have sold many more copies.

The only account we have of this, and that too a very partial account, is from a report in an English daily, which doesn’t show the Indian security establishment in good light. This report states that when retaliatory options were considered, the Army asked for three weeks’ time for a strike, the IAF said it didn’t have any coordinates for surgical strike targets from RAW, and the silent service kept silent as the terrorists slipped in through their exercise area. The PM seemed only to want an assurance that it would not escalate into a Pakistani nuclear attack. Since no assurances were forthcoming, to do nothing was the preferred option. How far this is true is anybody’s guess? But Mr Menon could have given us details of the options discussed as he was there. But he doesn’t tell us who played with what bat!

Some years ago I read the memoirs of Justice Pingle Jaganmohan Reddy, Down Memory Lane. It was a badly printed book at the Secunderabad Club library but a superb travel down time. It described in detail the Hyderabad he grew up in and the Hyderabad state where he began his career. The judge not only described people and events of the time as he saw them, but also filled the reader with local colour and flavours. When I read it I immediately thought that this was the kind of book every important person who holds high office must write. Almost every page was a picture painted with a fine brush. Reading it one almost lived those times. It was not self-serving nor was there any self-glorification. Less distinguished people who have held high office have also written, but more out of vanity than to leave a record of the times and their perceptions of them.